Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly present in many fields, including literature. In 3/2025, AI-written short stories stirred the international literary community. Domestically, discussions abound regarding AI's impact and how to apply the tool to literary creation. Translator Tran Tien Cao Dang shared his views on this topic.

Cao Dang noted that the key to using AI in creative work is maintaining a human imprint. He recounted a recent experience where he was asked to translate a novel. Upon opening the file, the first thing he noticed was the scattered em dashes '—', a common and often wearying hallmark of AI-generated text. He informed the author that their text bore too many AI hallmarks.

Cao Dang, who regularly uses AI, acknowledges that many of his colleagues—writers, translators, and editors—also use the tool. He stresses that no matter how or to what extent AI is used, the final product must retain a distinct human touch. If a creation is heavily flavored by AI, polished yet bland, and lacking personality, it signals a potential dead end for creators and humanity alike.

Cao Dang expressed concern about the literary world shifting towards mass production of words, where speed and superficial smoothness impress more than the writer's depth of experience. He predicts that AI will increasingly dominate market-driven and entertainment literature, with some readers accepting or even preferring AI-generated works. He suggests that in the near future, human-written creations might become a niche literature, read by few but possessing unique qualities and value, similar to the print editions of today's lifestyle magazines. In this scenario, authentic literature will become a luxury for the masses, but it will persist.

Addressing the trend of people accepting bland AI-generated texts as long as they are "standard" and "sufficient," Cao Dang drew a parallel to the rise of AI singers on YouTube. These AI voices, some personified with names like An Nhien, Lan Chi, and Linda, are often good, even excellent. Some listeners exclaim, "From now on, I'll only listen to AI singers." While this is a personal choice, Cao Dang emphasizes that many individuals will continue to seek human voices. Similarly, he believes many will still want to read human-written works. The boundary between human-written and AI-generated literature is increasingly difficult to define, but it is not nonexistent, nor does it mean no one is capable of clearly seeing that boundary.

|

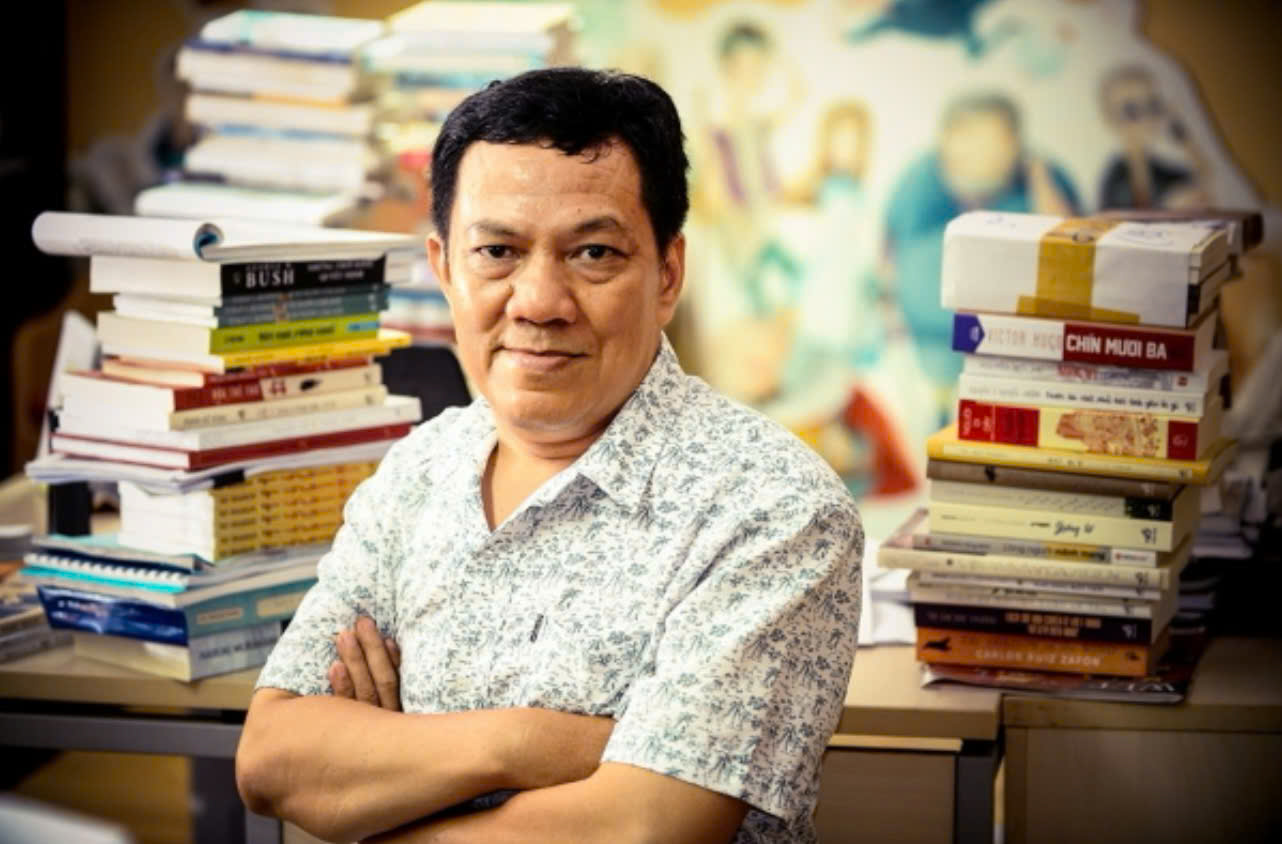

Translator Tran Tien Cao Dang. He has translated many books, including "The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle" by Haruki Murakami and "If on a Winter's Night a Traveler" by Italo Calvino. *Photo: Nha Nam* |

The widespread issue of AI poetry and literature in today's literary landscape raises questions about whether it is merely an inevitable technological phase shift or a serious threat to creativity, writing ethics, and reader trust. Cao Dang views authors and poets who become "addicted" to AI, retaining a machine-like voice, allowing words to flow smoothly but soullessly, and then publishing it as their own creation, as "killing themselves." They are removing themselves from the shrinking community of those who continue to write from their own minds and hearts, rather than through a machine.

Discerning readers will recognize creations completed from the heart and mind of a specific, private, and distinctive individual, distinguishing them from "works" churned out in endless batches from servers. Judges in literary competitions and award selection committees must be even more so. Every individual has a duty to elevate themselves; otherwise, AI and talented individuals will surpass them.

In an era where words are being flattened by the speed and convenience of machines, we must remind ourselves: Literature, ultimately, remains a work of talent, conscience, personality, and the author's responsibility to the reader.

Nguyen Hoang Anh Thu