"Why me?" Seles has every reason to ask. But at 51, after the latest storm, she's learned that self-pity gets her nowhere. The former tennis player just needs to stay afloat and find a new shore. "As I tell the young people I mentor: the ball bounces, and you have to adapt," Seles says.

|

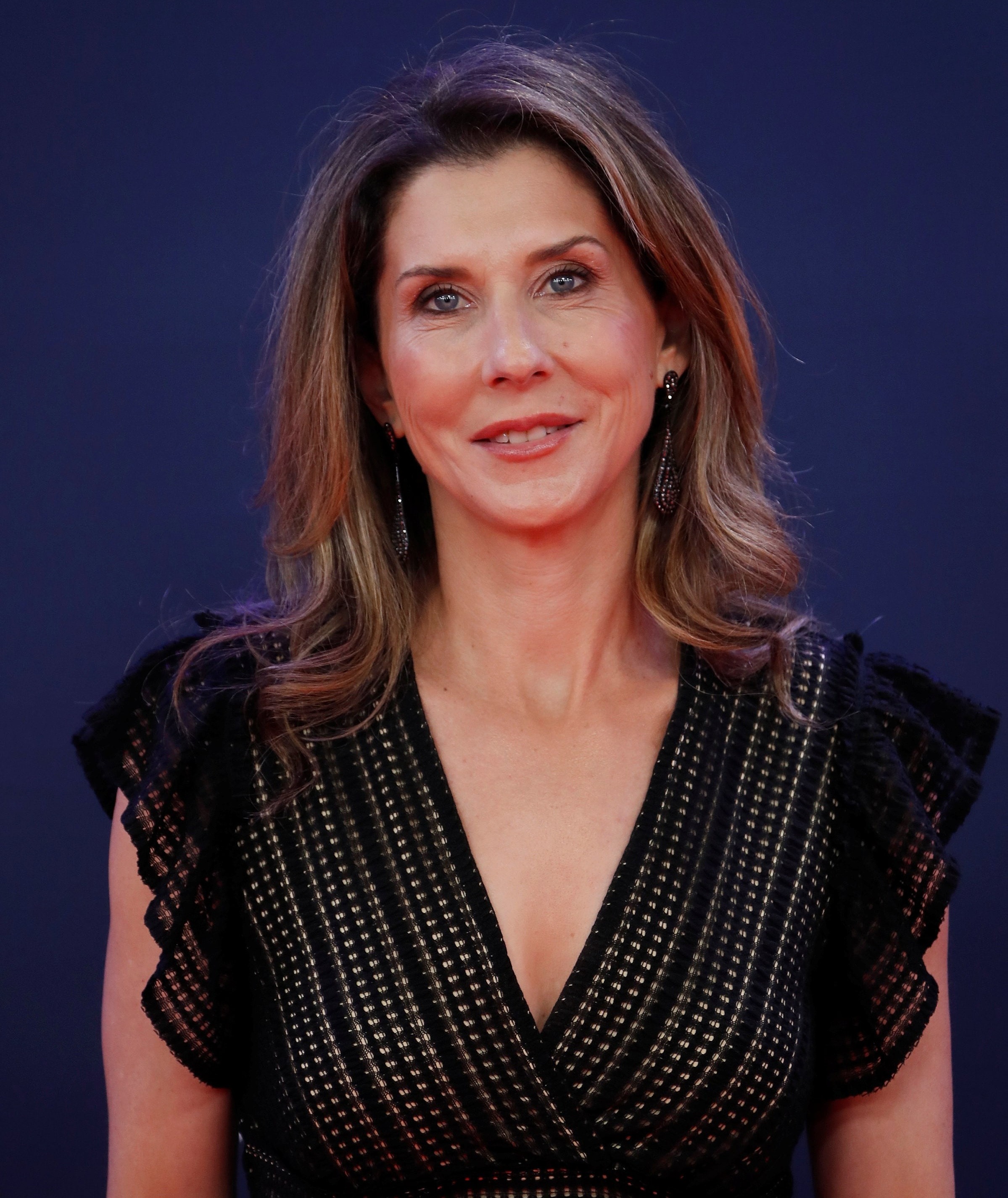

Seles battling myasthenia gravis at 51. Photo: AP |

That's what she's been doing since 2022 when diagnosed with myasthenia gravis, a rare neuromuscular autoimmune disease causing fatigue and muscle weakness. With no cure, even blow-drying her hair is a challenge for Seles, who once unleashed powerful two-handed forehands and backhands.

Discussing this latest challenge, Seles recalls previous restarts, forgetting everything and beginning anew. In a way, it's like a tennis player starting over after every game, set, and match.

The first restart was leaving Novi Sad, Yugoslavia (now Serbia), with her brother Zoltan for Nick Bollettieri's Florida academy. There, Seles honed the powerful tennis style her father taught her in a parking lot, using a net strung between two cars. 12 years old, Seles had never spent a night away from her parents, knew no English, and had to grow up fast.

A few years later came another transformation: from Monika Seles to Monica Seles. At 15, she debuted professionally. A year later, she was a pro. At 16 and 6 months, she defeated Steffi Graf in the French Open final, becoming the youngest Grand Slam champion. The next year, at 17, Seles became the youngest world number 1 at the time.

"Fame, money, attention changed everything. People treat you differently, and it's hard for a 16-year-old to handle. It's strange that at 16, you create jobs for others. You become a ‘company’, but you know nothing. As a teen, you're struggling to understand who you are, or even what hair color you want that week," Seles says.

|

Seles (left) and Graf in the French Open final, June 1990. Photo: Tennis Majors |

Seles’s tennis – anticipating opponents, powerful shots, and unwavering belief – became the standard. Young girls imitated her two-handed grip and grunts. Some opponents, like Graf, found the grunts annoying, but Seles insisted they aided her focus, not to distract.

Tensions flared in the 1992 Wimbledon final against Graf. After criticism, Seles stopped grunting but lost. Notably, two-time Oscar winner and tennis fan Peter Ustinov told a friend, "I wouldn't want to be in the hotel room next to Seles on her wedding night."

At 19, Seles faced an unknown enemy: Gunther Parche, a lathe operator from Nordhausen, Thuringia, Germany, living with his aunt. He traveled 300 km to Hamburg for the Citizen Cup. For three days, he followed Seles: hotel, restaurant, court. Seles later recalled noticing the man with a nylon bag, unaware it contained a sausage, 3,000 Deutsche Marks, pajamas, and a 23cm boning knife.

Seles didn't know Parche was obsessed with Graf, writing her long letters, sometimes sending Graf's mother 100 marks for flowers. To Parche, Seles threatened Graf's dominance.

On 30/4/1993, during a changeover in the second set against Magdalena Maleeva, as Seles sipped water, Parche stabbed her in the back. Luckily, she leaned forward to look at Christoph Werle, a scoreboard operator who saw the knife. His shout likely saved her life.

Seles never returned to Germany, even for Parche's trial. He received a two-year suspended sentence for grievous bodily harm, not attempted murder, deemed mentally unfit. He served no time. Seles endured a harsher sentence.

The knife penetrated 1.5 cm near her fourth thoracic vertebra. The mental shock was worse. Seles isolated herself, ignoring calls. The cheerful, energetic girl vanished. "Just thinking about Hamburg breaks my heart," her father, Karolj, recalled. The attack, on a tennis court where Seles felt safest, shattered her confidence. The prodigy disappeared, facing a crisis of self-worth.

"I went from training 5, 6 hours daily, surrounded by people, to nothing. I learned who my true friends were, a lesson about human nature," she said. Seles developed depression and binge eating disorder, filling the void with junk food, sneaking into the kitchen at night for chocolate chip cookies, chips, Pop-Tarts, and ice cream. "Food was the only way to suppress my demons. I controlled the court, not what I ate," Seles confessed.

Simultaneously, her father battled stomach cancer and died. Food became Seles’s sole comfort. She gained 20 kg. "Tennis is about image, sponsorships, appearance. When I gained weight, people stared, thinking, 'Why did she let herself go?' Sponsors asked, 'Look at you, what happened?' I wanted to say, 'I'm still me, the rest doesn't matter.'"

|

Seles gained weight due to uncontrolled eating after the stabbing. Photo: AP |

Discussing mental health was taboo in sports, especially for Seles with an all-male team. She isolated herself. "I was lonely. That generation was male-dominated – agents, coaches. Severely depressed, but a strong athlete, it was hard to admit it, let alone to the world. The men didn't understand emotions, only results. It took a long time to overcome."

Now, Seles is proud of that restart. "I had to figure things out alone, giving me strength no one can take away. For almost 10 years, I learned a healthy relationship with food."

One problem solved, another arose. At 30, a three-month leg cast stopped her tennis, ending the eating disorder. "I thought, 'I'll gain weight.' I was scared because I knew I'd be unhappy. But for the first time, I eliminated all nutritionists, coaches, advisors. I had to face my emotions."

Sharing her struggles, many athletes, especially female tennis players, contacted Seles. "I hope any young girl entering sports knows it's okay to have weight or eating issues and be open. It's a battle, and we take small steps. More female agents and coaches would be great."

In team sports, female athletes often discuss sisterhood. Seles lacked that. All tennis players, except Gabriela Sabatini, voted against her retaining the number 1 ranking. That betrayal revealed her world's reality. "It showed me tennis is a business. You have no friends. But Gaby disregarded fame, career, money, caring about me as a person."

|

Navratilova, a rare female superstar, supported Seles's return to number 1. Photo: AFP |

She returned after 837 days in August 1995. Thanks to Martina Navratilova, then WTA President, she shared the number 1 ranking with Graf, called "number 1bis". Navratilova vehemently argued for Seles's co-number 1 status; she believed Seles’s absence was unavoidable and unfair to lose her ranking due to a criminal act, not performance. Ironically, Navratilova once delayed Seles’s ascent to number 1 by a week after defeating her in the Virginia Slims final in 3/1991.

The attack rewrote tennis history, and Seles looks forward. She wants her story, with its storms, to inspire others. "It's hard to be friends competing for a Grand Slam. But some players became friends." One is two-time Wimbledon champion Petra Kvitova. They never played each other, but bonded after Kvitova's hand was stabbed by a home intruder in 2016. Not tennis, but shared trauma connected them.

Today, Seles is married to an older billionaire philanthropist, a spokesperson for a pharmaceutical company developing binge eating disorder treatments, and a Laureus Sport for Good Foundation ambassador.

Seles’s near-disappearance from tennis in 2019 is understandable. She experienced extreme weakness. On court, she saw two balls. The pandemic delayed diagnosis. After two years of tests, she received the myasthenia gravis diagnosis, a chronic illness affecting 150-200 people per million worldwide. "I'd never heard of it, on the news or from anyone," she said.

|

Seles at the Laureus Awards, 2/2019, Monaco. Photo: Reuters |

Some days, Seles plays tennis, pickleball, and walks her dog. Not always. "Some days are brutal," she shares. Seles will adapt, this time to the illness's demands. Adapting is what everyone does. The ball bounces, and we see where it lands.

Hoang Thong (via Gazzetta dello Sport and Los Angeles Times)