When President Donald Trump ordered an attack on Iran's nuclear program last month, he was confronting a crisis the US had inadvertently sown decades earlier by providing Tehran with the "seeds of nuclear technology," experts say.

Nestled in the northern suburbs of Tehran is a small nuclear reactor, used for non-military scientific purposes. It was not a target in the 12-day Israeli operation in June, which aimed to "eliminate Iran's nuclear weapons capability".

|

President Dwight D. Eisenhower (left) with Iranian King Mohammed Reza Pahlavi in Tehran in 1959. Photo: AP |

President Dwight D. Eisenhower (left) with Iranian King Mohammed Reza Pahlavi in Tehran in 1959. Photo: AP

This Tehran Research Reactor is a symbolic device. It was transferred to Iran by the US in the 1960s as part of President Dwight D. Eisenhower's "Atoms for Peace" program.

The program shared nuclear technology with Washington's allies, countries eager for economic modernization and closer ties with the US in a world divided by the Cold War.

Today, this reactor is not involved in Iran's uranium enrichment process. It uses nuclear fuel too weak to produce an atomic bomb. However, it is a testament to how the US introduced nuclear technology to Iran, then led by a secular, pro-Western monarch.

The nuclear program quickly became a source of national pride for Iran. Initially seen as an engine of economic growth, it later, to the West's astonishment, became a potential source of ultimate military power.

"We gave Iran the starter kit," said Robert Einhorn, a former arms control official who participated in US-Iran nuclear negotiations.

"At the time, we weren't too worried about nuclear proliferation, so we were pretty lax about transferring this technology," said Einhorn, now a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington. "We helped many other countries get into the nuclear field."

The "Atoms for Peace" program stemmed from President Eisenhower's December 1953 speech, in which he warned of the dangers of a nuclear arms race with the Soviet Union and pledged to lead the world "out of this dark chamber of horrors into the light".

President Eisenhower explained that the world needed a better understanding of such a destructive technology and that its secrets should be shared for constructive purposes.

"It is not enough to take this weapon out of the hands of the soldiers. It must be put into the hands of those who know how to strip its military casing and adapt it to the arts of peace," he stressed.

But this gesture did not seem to stem purely from altruism. Many historians believe President Eisenhower was trying to cover up the US's own intensified nuclear weapons research.

He was also influenced by scientists, including J. Robert Oppenheimer, who helped develop the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, Japan, less than a decade earlier.

The Eisenhower administration also saw the program as a way to influence key players on the global Cold War chessboard, including Israel, Pakistan, and Iran. These countries were provided with nuclear information, equipment, and training for peaceful uses such as science, medicine, and energy.

The Iran that received the US research reactor in 1967 was very different from the country led by clerics and generals today. At that time, Iran was led by Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi. Educated in Switzerland, he ascended to the throne in 1941. His power was greatly consolidated after the 1953 coup that ousted Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddegh, a coup backed by the US Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). Prime Minister Mossadegh had resisted Western influence by nationalizing the oil industry.

Shah Pahlavi was determined to modernize the nation and transform Iran into a world power with US support. He promoted secularism and Western education, but ruthlessly suppressed political opposition. He diminished the influence of religion in life, banned women from wearing veils, encouraged modern art, and focused on literacy and infrastructure development.

|

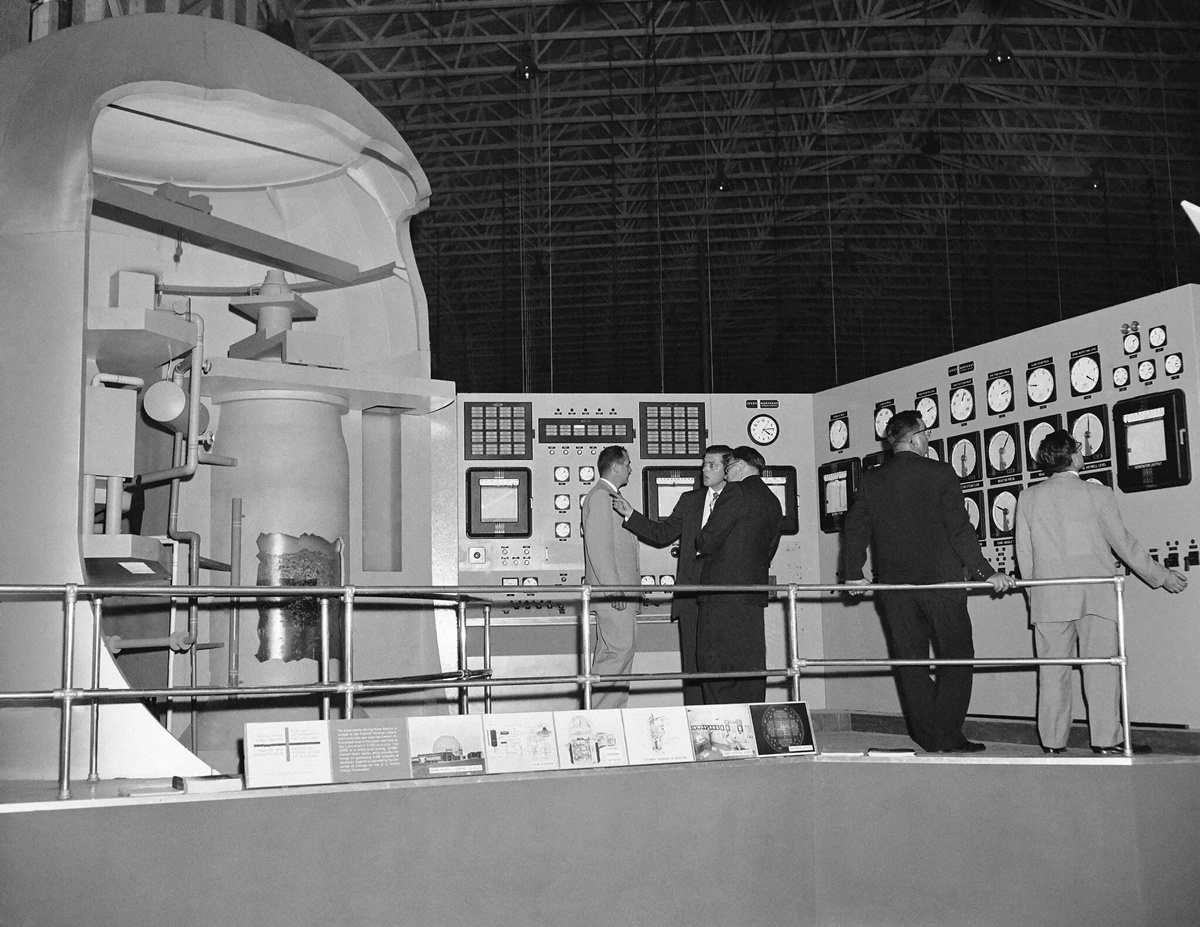

A boiling water reactor at the US exhibit at the "Atoms for Peace" exhibition in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1958. Photo: AP |

A boiling water reactor at the US exhibit at the "Atoms for Peace" exhibition in Geneva, Switzerland, in 1958. Photo: AP

Fueled by the "Atoms for Peace" program, Shah Pahlavi poured billions of dollars into Iran's nuclear program. He saw it as a pillar of national energy independence and national pride. The US regularly welcomed young Iranian scientists for special nuclear training at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

In the 1970s, Iran further expanded its nuclear program by signing a series of agreements with European allies. During a 1974 visit to Paris, Shah Pahlavi was warmly welcomed at Versailles before signing a 1 billion USD deal to buy five 1,000-megawatt nuclear reactors from France.

Initially, Iran was an ideal model for the peaceful use of nuclear energy. Shah Pahlavi was then much admired in the US.

A New England utility company ran an advertisement featuring the Shah with the message: "Mr. Pahlavi wouldn't build nuclear plants if he had any doubts about their safety. He'll wait, like many Americans want."

But even though the US persuaded Iran to sign the 1968 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty, in which Tehran accepted international safeguards and pledged not to pursue nuclear weapons, doubts about the Shah's intentions grew in Washington.

A 1974 article pointed out that Iran's reactor deal with France "made no public mention of safeguards against their use as the basis for nuclear weapons".

Soon, the Shah began talking about Iran's "right" to produce nuclear fuel domestically – a capability that could also be applied to developing nuclear weapons. He criticized discussions about limiting Iran's nuclear activities from outside as violations of national sovereignty. These are the same arguments used by Iran's current leaders.

As the US continued to express concerns, the Shah sought nuclear assistance from other countries: Germany helped Iran build more reactors, and South Africa supplied raw uranium, also known as "yellowcake".

By 1978, unable to hide its unease, the Carter administration insisted on revising the contract for the sale of eight US reactors to Iran. The new version prohibited Iran from reprocessing any US-supplied fuel for the reactors without permission, if there were suspicions it could be used for nuclear weapons.

The US reactors were never delivered. In 1979, the Islamic Revolution erupted, fueled in part by popular resentment of the US, which had backed the Shah. Pahlavi was overthrown.

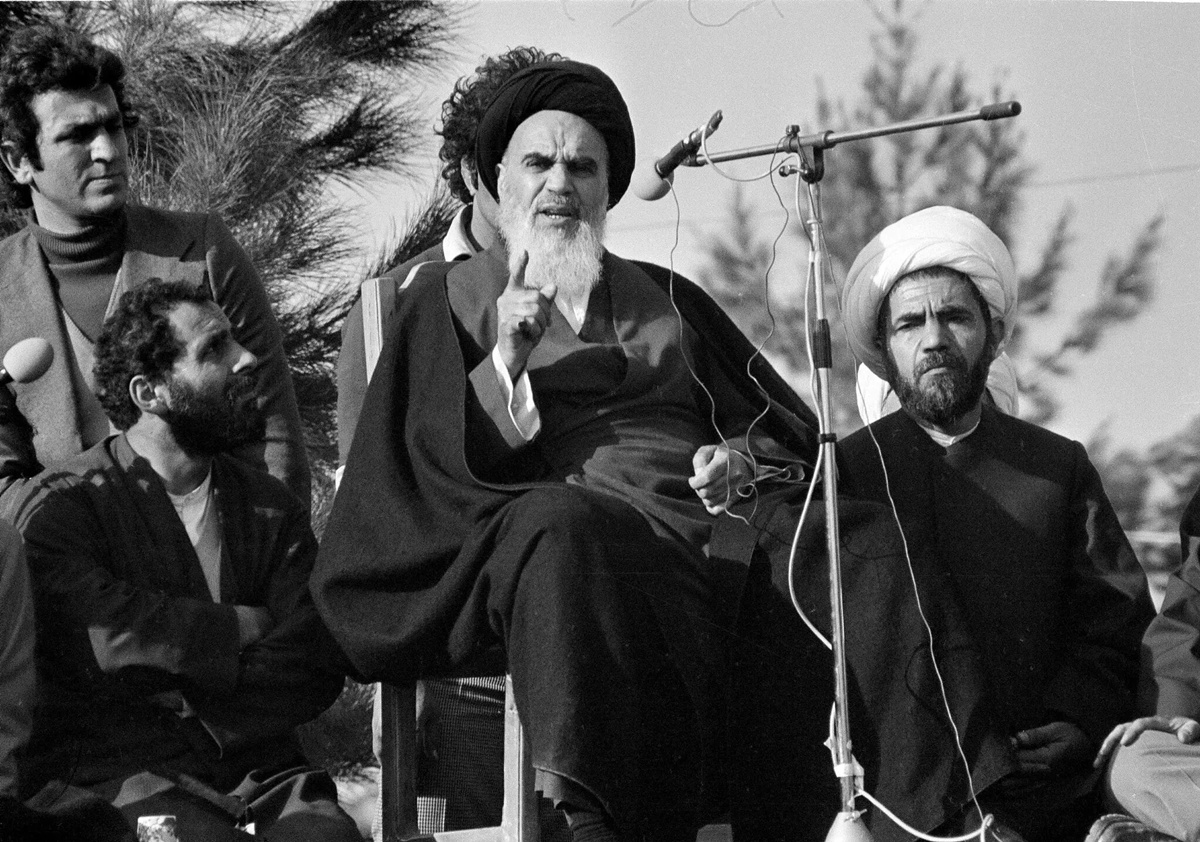

For a time, Iran's nuclear ambitions seemed no longer a Western concern. Iran's clerical leaders, headed by Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini, initially showed little interest in continuing a costly project associated with the Shah and Western powers.

But after the devastating eight-year war with Iraq in the 1980s, Khomeini reassessed the value of nuclear technology. This time, Iran turned east, toward Pakistan, another country that had benefited from the "Atoms for Peace" program. Pakistani scientist Abdul Qadeer Khan sold Iran centrifuges to enrich uranium to bomb-grade purity.

Gary Samore, a former top White House nuclear official under the Clinton and Obama administrations, said Iran's purchase of centrifuges from Pakistan was the real reason the country's nuclear program escalated into a global crisis.

"Iran's uranium enrichment program did not result from US assistance," he said. "The Iranians got centrifuge technology from Pakistan, and they developed their own centrifuges based on that technology, which was itself based on European designs."

However, these centrifuges are used by Iran's nuclear management system, which the US helped create decades ago.

For years, Iran secretly expanded its nuclear program, building more centrifuges and enriching uranium. After Iran's secret nuclear facilities were discovered in 2002, the US and its European allies demanded that it stop enriching uranium and disclose all its nuclear activities.

Iran has for years insisted it has never sought to develop nuclear weapons, citing a religious decree by Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, who has been in power since 1989, banning such weapons. They accuse Israel of "fabricating" the description of Iran's nuclear activities as a security threat.

|

Iranian Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini speaks in Tehran in 1979. Photo: AP |

Iranian Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini speaks in Tehran in 1979. Photo: AP

After more than 20 years of diplomacy and Israeli and US operations, tensions surrounding Iran's nuclear issue remain unresolved. Mr. Trump initially claimed the June 21 attack had "completely wiped out" three Iranian nuclear sites, but experts say much remains intact.

A leaked US intelligence report suggested that the US attack could only delay Iran's nuclear program by "a few months". The Pentagon earlier this month said the program had been set back by nearly two years.

Observers are now pinning their hopes on the prospect of resuming negotiations and reaching a comprehensive nuclear agreement between Iran and other parties to address the core issue.

"Iran will face the difficult decision of whether to continue pursuing its long-term nuclear goals, and if so, how," said Gary Samore, an analyst for the Financial Times.

Vu Hoang (According to AP, AFP, Reuters)