Once a month, around midnight, guards at the Saydnaya prison on a hillside outside Damascus would call the names of dozens of prisoners at a time to a room. There, guards would place nooses around the prisoners' necks and then kick the tables out from under them. The prisoners' last gasps echoed in the silent darkness.

By mid-3/2023, the pace of executions at Saydnaya prison had increased significantly, according to six witnesses who were imprisoned there under President Bashar al-Assad.

|

People gather outside Saydnaya prison in 12/2024. Photo: AFP |

People gather outside Saydnaya prison in 12/2024. Photo: AFP

"They gathered 600 people to execute in three days, about 200 people each night," said Abdel Moneim al-Qaid, 37, a former Syrian rebel. Al-Qaid was arrested after surrendering under an "amnesty agreement" with the government.

The 2023 mass executions at this "death prison" are revealed through accounts from former prisoners, former government officials, and hundreds of pages of documents found at Saydnaya and other Syrian security offices.

Saydnaya, known in government documents as "Military Prison Number One", is the largest detention and execution center among dozens of prisons established under Assad.

For the past 14 years, the name "Saydnaya", after the small mountain town where the prison is located, has become a source of terror for Syrians. People often use the phrase "disappeared in Saydnaya" to refer to someone being arrested and never returning.

In addition to the thousands killed in organized executions, former prisoners and war crimes experts say thousands more may have died at Saydnaya from torture and harsh prison conditions.

Imprisoned in lice-infested, steel-walled cells with a single slit for a window, prisoners were forbidden to look guards in the eye. If they did, they would be severely beaten and left on the floor.

"Saydnaya is a terrifying nightmare. Most of those who enter never leave," said Ali Ahmed Al-Zuwara, 30, a farmer outside Damascus who was arrested in 2020 for dodging military service.

According to the Syrian Observatory for Human Rights, approximately 160,123 Syrians have "disappeared" in more than 10 years of civil war, mostly those imprisoned in Saydnaya.

Some families of the missing still hope their loved ones are alive. Others have held funeral services in absentia, accepting they are no longer living, but still wondering how or when they died.

"Although we knew he was imprisoned in Saydnaya, we didn't know what happened. We never received his body," said Dina Kash, wife of Ammar Daraa, a wholesaler who was arrested and disappeared in 2013 at age 46.

Thanks to documents found in an intelligence headquarters after the Assad regime fell, her family received confirmation last December that Daraa had been taken to Saydnaya.

"We have to pray to God to have mercy on his soul, but we always have to add 'whether he is alive or dead'," Kash said.

Military Prison Number One in Saydnaya was built in the 1980s under Hafez Assad, Bashar al-Assad's father.

In 2011, during the "Arab Spring" uprisings that toppled the presidents of Tunisia and Egypt, thousands of Syrians took to the streets demanding greater political freedom.

When the uprising broke out, Mohammed Abdel Rahman Ibrahim, a soft-spoken 26-year-old, was tutoring students with his advanced math degree. He still lived with his parents on the southern edge of Damascus, in a neighborhood of car mechanics and delivery drivers.

That summer, Ibrahim was drafted and sent to guard an airbase in the north of the country, where government fighter jets took off to bomb rebel positions in nearby Aleppo.

He deserted in 1/2013, joining a rebel brigade near Damascus. After a few months, however, Ibrahim became exhausted and abandoned the fight. Fleeing to a rebel-held area in southern Syria, he spent four years teaching math and working at a small corner shop, living as an exile, unable to return home to Damascus for fear of arrest.

In 2018, the government announced an amnesty for some rebels in the south. Tired of living in fear as he passed through government checkpoints, Ibrahim decided to accept the deal.

He surrendered at a military police headquarters in Damascus. Upon arrival, Ibrahim presented his ID and a copy of the amnesty papers to an officer.

"Who gave you this?" the officer shouted, throwing the papers to the floor.

After four days of interrogation, he was blindfolded and taken to the Syrian Air Force Intelligence headquarters at Mazzeh airbase. Officers demanded he sign a document confessing to killing government soldiers.

At first, Ibrahim refused. He was immediately beaten with batons and hung from the ceiling. After being lowered, the officers threatened to harm Ibrahim's mother and sister, forcing him to comply. Ibrahim then signed and fingerprinted the confession without being allowed to read it.

|

Prisoner uniforms and other belongings left behind in a cell at Saydnaya prison. Photo: WSJ |

Prisoner uniforms and other belongings left behind in a cell at Saydnaya prison. Photo: WSJ

"Maybe I signed my own death warrant. I don't know," said Ibrahim, now 40.

An intelligence officer told Ibrahim that he would "never see the sun again" as he pushed him into the back of a truck. One morning in 4/2019, Ibrahim and about 40 other prisoners were taken to Saydnaya.

There, guards stripped Ibrahim naked and shoved him into a rubber tire so they could beat his limbs. After the initial torture, he was locked with seven other men in a cell barely large enough for all of them.

Bruised, bleeding, naked, and shivering from the cold, the men huddled together for warmth in the darkness. The cell's single toilet overflowed onto the floor around them.

"I'm sure I'll die before morning," one man said.

Everyone in Ibrahim's cell survived until the next morning. The guards opened the door, gave them gray uniforms, and led them upstairs to regular cells.

What Ibrahim experienced the previous night was "standard procedure", which some former prisoners called the "welcome party". It was like a ritual to crush their will.

Some prisoners died during this initial beating, often receiving up to 100 blows to the legs. Bashar Mohammed Jamous, 35, a former rebel soldier who was imprisoned in Saydnaya, said he had his left foot amputated after the "welcome" beating.

This was also an introduction to the life that awaited the prisoners inside the prison, where they were deprived of their most basic human rights. They were forbidden to speak loudly and were stripped of their shoes, books, and writing materials.

Strong winds blew through the prison almost year-round. The men shivered in their paper-thin uniforms in unheated cells.

They recounted that many were forced to drink their own urine, were sexually assaulted, and were constantly beaten by guards with water pipes or plastic tubes. Jamous remembers when they showered, the blood from the beatings would mix with the soap and water, flowing across the floor.

"Every time they opened the door, they beat you," Ibrahim said.

Prisoners were often starved or deprived of drinking water. A crowded cell received only a single cup of rice for the entire day’s ration. The lack of food emaciated them. Once, the guards cut off the water for 17 consecutive days. A prisoner named Bassam Rahman had to drink water from the toilet, which caused him to die from illness a few days later, recalled Mahmoud Omar Warde, 34, Rahman’s cellmate.

"We started with 25 people. In the end, there were only 8 left," said Warde, who now lives in the town of Afrin in northern Syria. "All those who died, died right in front of us in the cell, mainly from beatings."

In the summer of 2011, as Assad began cracking down on the uprising, Muhammad Afif Naifeh was sitting in his Damascus office when a group of security officials appeared. They asked him to gather people and take them to a cemetery in the countryside south of the capital.

At the designated location, a cemetery in the town of Najha, the security personnel brought a refrigerated truck containing 10 bodies and ordered them buried. Naifeh's body trembled.

"I didn't ask any questions," he said.

In the following weeks, security personnel came constantly, asking for more people as the number of bodies needing burial continued to increase, always at night. Once, an air force intelligence officer gave Naifeh a list of bodies. They were not named, only numbered.

"That's when I realized they died from torture," Naifeh said.

Government documents reveal that inside the government's secret system of military hospitals and morgues, bodies shipped from Saydnaya and other security facilities were piling up.

By 2013, the Najha cemetery was full. Naifeh and his team were summoned to a vacant lot on the northern outskirts of Damascus. There, near the town of Qutayfah, they were instructed to continue digging graves for the increasing number of bodies.

According to analysis of satellite imagery from the German Aerospace Center conducted for the war crimes trial of a Syrian official in Germany, the mass grave at Qutayfah expanded from 19,000 to 40,000 square meters between 2014 and 2019.

During this period, two to three trucks a week brought bodies to Qutayfah, sometimes up to hundreds of people. Some bodies had marks around their necks. Others still had nooses around their necks, which Naifeh later realized meant they came from Saydnaya.

|

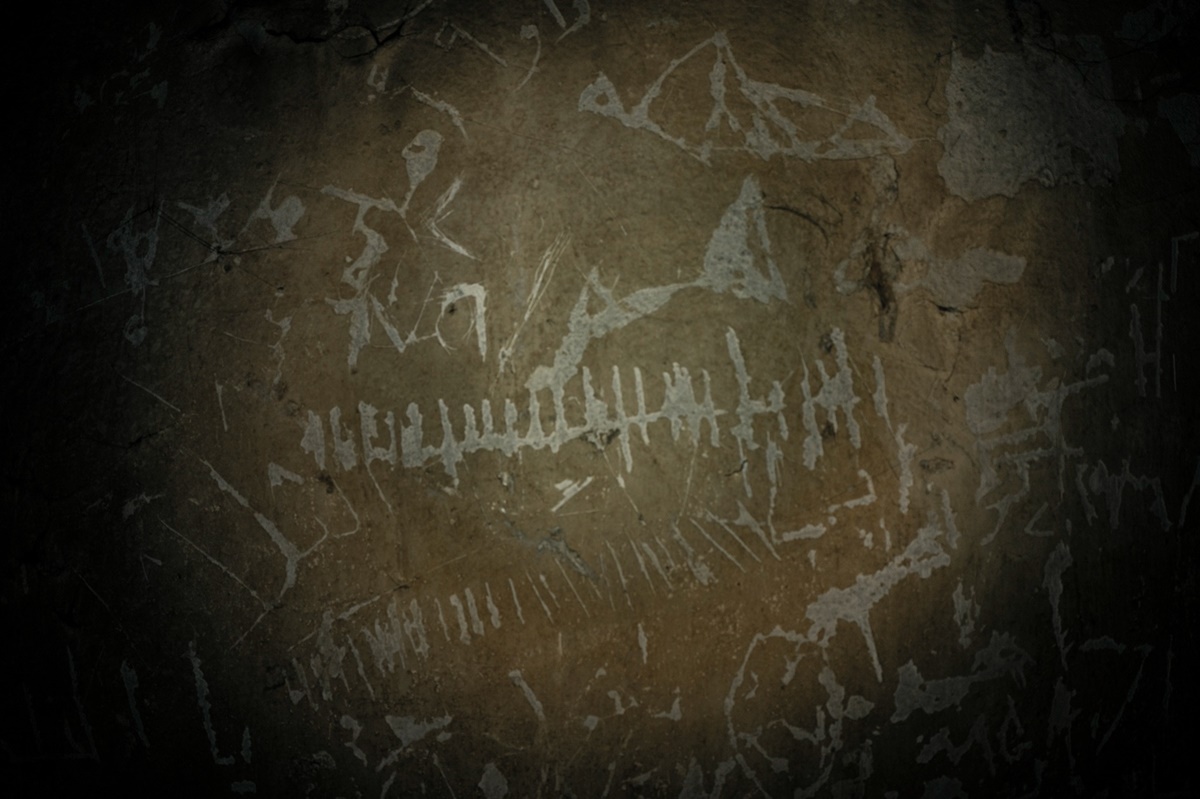

A calendar etched by prisoners on the wall of a solitary confinement cell inside Saydnaya prison. Photo: WSJ |

A calendar etched by prisoners on the wall of a solitary confinement cell inside Saydnaya prison. Photo: WSJ

Naifeh defected in 2017 and fled to Germany. There, he testified in the war crimes trial against a Syrian government official. For years, he kept his identity secret.

"It destroyed me emotionally and physically," he said. "I've had nightmares ever since I came to Germany."

Today, the mass grave is a muddy field next to a highway, adjacent to several military bases.

Mohammed Ibrahim returned to Saydnaya prison for the first time as a free man in February. He walked through the building, pointing out his old cell and the room where the "welcome" torture took place.

"I still hear the screams in my head and the sounds of the whips," he said. "It's as if it's all happening before my eyes."

At the same time, Ibrahim said that visiting the prison had helped him gain closure.

"The first few days after I got out, I was afraid to sleep. I kept thinking it was just a dream and I would wake up back in Saydnaya," he said. "Now, I know it's really over."

Vu Hoang (According to WSJ, Aurora Israel, AFP, Reuters)