|

The late Deputy Prime Minister Vu Khoan. Photo: VGP |

During a jovial dinner in Bali, Indonesia, years ago, a remark by ASEAN diplomats stunned Vu Khoan: "The matter discussed yesterday has been agreed upon!"

"Agreed upon when? How come I didn't know?", Vu Khoan, then Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, asked. His ASEAN colleagues replied that they had reached an agreement on the golf course that morning.

When he protested, "Vietnam wasn't present at the golf course this morning", the ASEAN officials responded half-jokingly, "That's not our fault, it's yours for not playing golf".

This anecdote, recounted by the late Deputy Prime Minister Vu Khoan in his book "Stories of the Profession, Stories of the Diplomatic Profession", encapsulates Vietnam's challenging journey of joining and participating in ASEAN. Learning that diplomacy doesn't just happen at the negotiating table, he resolved to learn golf to bridge that gap, with a single goal: to bring Vietnam closer to the region.

"I started playing golf out of political necessity, not out of any fashionable hobby," he wrote.

|

The moment Vietnam and the US announced the normalization of relations. Video: AP |

This story reflects the difficulties and persistent efforts of Vietnamese diplomats to integrate the country into the international community. In the 1980s, following the long struggle for reunification, Vietnam faced another battle: overcoming international isolation, embargoes, and diplomatic ostracization.

"Vietnam was under siege by the US and the West, facing embargoes across all aspects of politics, economy, trade, and diplomacy. It's fair to say that Vietnam had no path to connect with the outside world," Ambassador Do Ngoc Son, former Director of the ASEAN Department, told VnExpress.

While the embargo tightened its grip on Vietnam externally, the domestic situation was equally dire. The post-war economy was in crisis, hyperinflation was rampant, and people faced immense hardship.

Meanwhile, the world was undergoing dramatic changes, with cooperation, integration, and globalization replacing confrontation. Vietnam faced a crucial choice: continue enduring the current predicament or find a way to break free and open the door to integration.

The 6th National Congress of the Communist Party in 1986 provided a path forward, declaring that Vietnam would "expand relations with all countries on the principle of peaceful coexistence". In this context, breaking the embargo and isolation was identified as the key to creating a peaceful, stable environment for Vietnam's economic development, according to Son.

A crucial decision was made: joining the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) would be the "breakthrough" to overcome the embargo and isolation.

"Why ASEAN? I think it's quite understandable. It's a geographically close region, with many historical and cultural similarities, making it easier to find common ground. Vietnam had also established diplomatic relations with most countries in the bloc. To go out, we first had to establish relations with our neighbors," Son explained.

ASEAN was founded on 8/8/1967 in Bangkok, with five original members: Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand. Brunei joined in 1984, and during this period, the bloc often stood in opposition to Vietnam.

Yet, ASEAN was also seen as the necessary gateway for Vietnam to re-enter the world stage. Normalizing relations and joining the Association would help Vietnam address both security and political legitimacy, Son said.

The late Prime Minister Vo Van Kiet also recognized ASEAN's role, stating that "more than any individual nation, ASEAN can be a bridge connecting Vietnam's economy with the world economy... ASEAN will be one of Vietnam's main partners, as a group of countries".

The ASEAN countries then had more developed economies than Vietnam, meaning Vietnam could benefit from their experience, capital, and markets.

"With a post-war crisis economy and a renovation process in need of capital, markets, and technology, joining ASEAN was the shortest path to those benefits," Son said.

Along with the ASEAN integration process, Vietnam would also eliminate the pretexts used to isolate the country, paving the way for cooperation with the region and the world.

"Vietnam needed to join ASEAN to play the big game... It was a life-or-death decision for Vietnam's benefit," assessed Ambassador Vu Quang Minh, former Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs.

Exploration and untying the knot

Foreign Minister Nguyen Co Thach sent the first signal to ASEAN during contacts between 1986 and 1987. At the Asia-Pacific Roundtable for Journalists in Ho Chi Minh City in 10/1989, General Secretary Nguyen Van Linh announced Vietnam's readiness to establish friendly relations with ASEAN and other countries in the region.

ASEAN gradually received these signals, as admitting Vietnam was also in the Association's interest. From its inception, ASEAN's goal was to build a community encompassing all 10 Southeast Asian nations.

Ambassador Son said ASEAN hoped that Vietnam, upon becoming a member, would lead the remaining group of Laos, Cambodia, and Myanmar to join, fostering cooperation and development with the original six members.

Ambassador Vu Quang Minh believed that Vietnam's normalization of relations with China in 1991 motivated ASEAN, as Vietnam was then seen as an important gateway to China's vast market.

Another important factor was the US announcement to lift the trade embargo and subsequently normalize relations with Vietnam on 7/11/1995. "This showed that all opposition and pressure on Vietnam were gone. Clearly, Vietnam had been recognized by major powers, and our Doi Moi policy had been effective in raising the country's standing," Ambassador Son said.

These factors created favorable conditions for Vietnam to make a "breakthrough" into ASEAN. However, Vietnam also understood that the biggest obstacle to normalization and ASEAN membership was the Cambodian issue.

After the Khmer Rouge regime was overthrown, Vietnam sent numerous officials and experts to Cambodia to assist in building local governments and restoring the socio-economy. However, this effort caused misunderstandings and tensions between ASEAN member states and Vietnam.

To address this, Vietnam actively participated in informal dialogue mechanisms like the Jakarta Informal Meeting (JIM), initiated by Indonesia, which served as a forum for Vietnam and ASEAN countries to discuss their differences regarding Cambodia.

In 1989, Vietnam withdrew all its volunteer troops from Cambodia as agreed between the two countries, fulfilling a noble and rare international obligation. Vietnam then participated in the Paris Conference on a comprehensive political settlement for the Cambodian issue.

After much diplomatic negotiation, the Paris Peace Accords on Cambodia were signed in 10/1991, ending years of tension between Vietnam and ASEAN and opening the door wider for Vietnam to join the Association.

In a 1991 interview with the Hong Kong-based Far Eastern Economic Review (FEER), Minister Nguyen Co Thach stated that Vietnam could join the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia (TAC).

The TAC, first signed in Indonesia in 1976, aims to promote lasting peace, friendship, and cooperation in the region based on respect for independence, sovereignty, territorial integrity, and non-interference in each other's internal affairs. Joining the treaty was considered a prerequisite for Vietnam's ASEAN accession.

Ambassador Son considered Minister Nguyen Co Thach's statement to an English-language magazine, rather than through traditional diplomatic channels, a noteworthy move. "This was Vietnam's exploratory step to gauge ASEAN's reaction," he said.

|

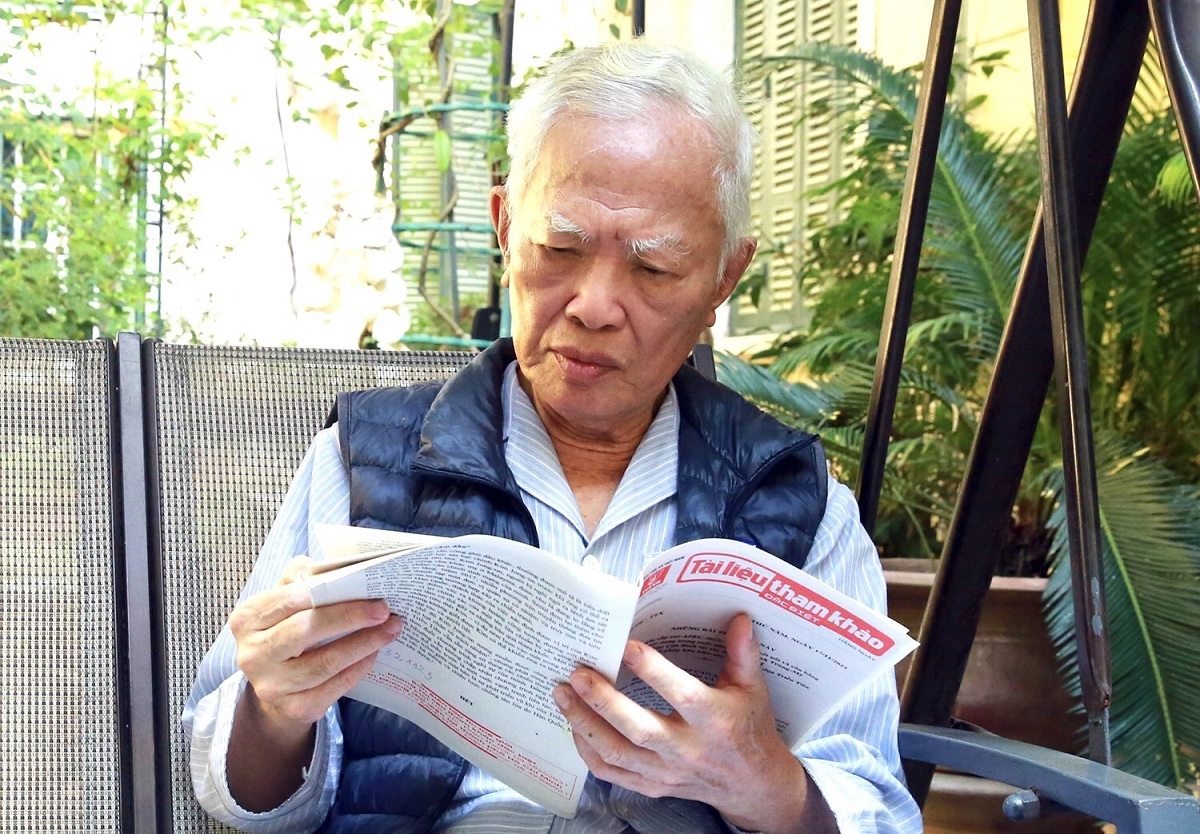

Ambassador Do Ngoc Son, former Director of the ASEAN Department, interviewed by VnExpress. Photo: Anh Phu

But "it takes two to tango", Ambassador Minh wittily remarked. Vietnam's ASEAN accession could not succeed with effort and goodwill from only one side. Throughout the process, ASEAN played a significant role in guiding and shaping a favorable political environment for Vietnam's regional integration.

Following Minister Nguyen Co Thach's exploratory move, the ASEAN Senior Officials' Meeting (SOM) in Bangkok agreed to admit Vietnam. Deputy Foreign Minister Vu Khoan then had to meet with the SOM to discuss procedures.

"I began by formally saying 'Your Excellencies...', but was immediately corrected by my ASEAN counterparts: 'There are no Excellencies here, only friends or colleagues'," Vu Khoan recalled about his initial encounters.

When ASEAN officials requested Vietnam to sign the Common Effective Preferential Tariff (CEPT) scheme before joining, Vu Khoan was taken aback and asked, "What is CEPT?".

The Vietnamese Deputy Foreign Minister's question surprised the ASEAN officials. "You don't know what CEPT is, and you want to join ASEAN?" they asked, then instructed him to discuss further with the head of the Thai SOM, who was then the Chair of the Economic Ministers' Meeting.

The two sides agreed that Vietnam would sign CEPT after joining ASEAN, and Vu Khoan had to "lead a multi-sectoral delegation on a tour of ASEAN countries to learn more".

ASEAN member states demonstrated their support for Vietnam according to their position and capacity. Indonesia, considered the "big brother" of ASEAN, played a key role in mediating and leading regional dialogue, initiating JIM1 and JIM2 as mechanisms for resolving the Cambodian issue between Vietnam and ASEAN.

Thailand invited Vietnam to participate in numerous economic seminars and forums as a potential partner, helping build trust and laying the foundation for Vietnam's economic integration into the region. Singapore provided technical assistance, training courses for Vietnamese officials, and advice on reforms aligned with ASEAN standards.

Malaysia, the Philippines, and Brunei also expressed their goodwill, welcoming Vietnam to the ASEAN community and contributing to the absolute consensus within the Association, a prerequisite for admitting new members.

In 7/1992, ASEAN countries invited Vietnam to attend the ASEAN Foreign Ministers' Meeting in Manila, Philippines, where Vietnam signed the TAC and gained observer status.

The observer status typically lasts five years, but by 1994, the Association hinted at admitting Vietnam.

"They asked if Vietnam felt ready to join ASEAN. It was a positive and subtle suggestion. ASEAN officials didn't want to create the impression that the Association was inviting Vietnam to join, but rather that we were doing so voluntarily. But that statement also signaled, 'We are ready to admit you'," Son said.

A few months after the US lifted its trade embargo on Vietnam, on 10/17/1994, Foreign Minister Nguyen Manh Cam formally applied for ASEAN membership. At the 27th ASEAN Foreign Ministers' Meeting (AMM) in Bangkok that year, the countries agreed to admit Vietnam as the 7th member in 1995.

A last-minute gamble

As preparations for Vietnam's admission neared completion, a last-minute incident threatened to derail the historic plan, forcing the Vietnamese delegation into a "high-stakes gamble" with their partners.

During the ASEAN Standing Committee (ASC) meeting in Brunei on 7/24-25/1995, while reviewing documents for submission to the 28th ASEAN Foreign Ministers' Meeting (AMM 28), the Vietnamese delegation discovered a draft declaration on the boat people issue, which had not been previously discussed.

This surprised everyone, as Vietnam had held bilateral discussions with each ASEAN country receiving Vietnamese refugees to resolve the boat people issue during the accession process.

"After learning this, I reported to the leadership in Vietnam and had my team investigate the draft's origin. I also rushed to meet the Secretary-General of Brunei's Ministry of Foreign Affairs, who was preparing for the meeting, to inquire about the newly arisen issue," recounted Son, then Director of the ASEAN Department.

The Vietnamese delegation learned that the boat people draft was proposed by Malaysia. Malaysia had also drafted a declaration on the Bosnia and Herzegovina war (1992-1995). Kuala Lumpur had sent 1,500 troops to support Bosnian Muslims, so "they wanted ASEAN to issue a statement supporting Bosnia and condemning the then-Yugoslav government," Son said.

However, Vietnam had stated its position of non-interference in the internal affairs of other countries, instead calling for dialogue to resolve conflicts. This stance made Malaysia concerned that Vietnam would reject the draft on the Yugoslav situation, so the boat people draft seemed intended to pressure the Vietnamese delegation.

The urgent task for the Vietnamese delegation in Brunei was to convince Malaysia to withdraw the boat people draft, otherwise, ASEAN membership was at risk.

With the admission ceremony just days away, Son said Vietnam decided to use a "psychological tactic", proposing to ASEAN that Vietnam's admission be postponed until the issue of Malaysia withdrawing the boat people draft was resolved.

"We understood that ASEAN would be very apprehensive about delaying the announced admission without a valid reason. They were also wary of the reaction from the Vietnamese public," he explained.

While firmly rejecting the boat people draft, Vietnam also showed goodwill by agreeing to a statement on Yugoslavia, provided it didn't specifically condemn any party. Finally, Malaysia agreed to withdraw the boat people draft, while Vietnam accepted the statement on Yugoslavia with wording adjustments aligned with its views.

"This is a memorable anecdote about ASEAN cooperation. In Vietnam, there's a saying 'a good beginning makes a good ending', but in this case, 'the beginning went well, but the ending... got a little stuck'," Son described, adding that it demonstrates the complexities of multilateral diplomacy, where unexpected situations always arise, requiring flexible and astute responses from diplomats.

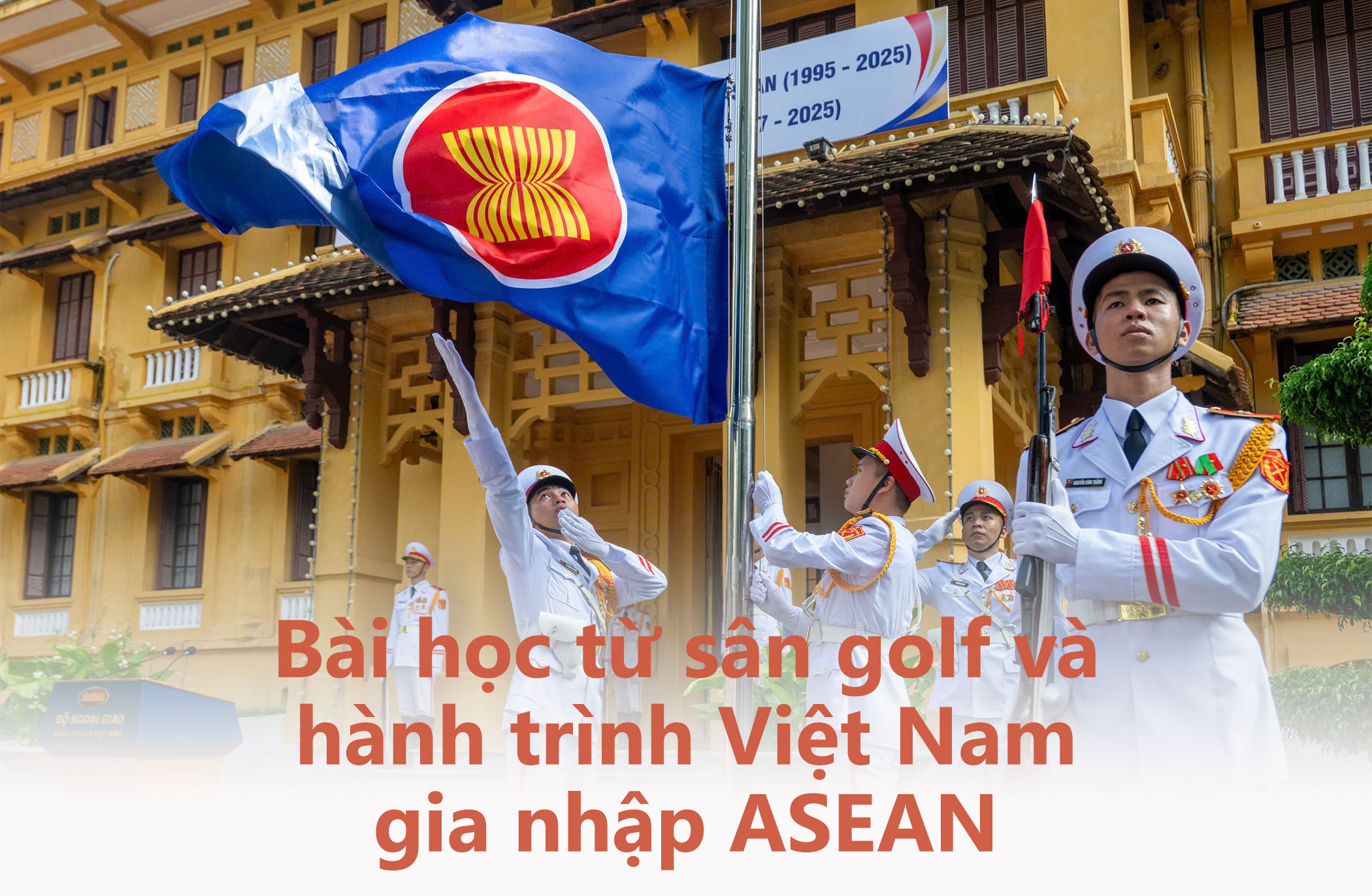

Finally, the momentous day arrived. On the afternoon of 7/28/1995, Vietnam's admission ceremony into ASEAN took place in a solemn atmosphere in Bandar Seri Begawan, the capital of Brunei. ASEAN Secretary-General Ajit Singh, Foreign Minister Nguyen Manh Cam, and numerous officials from member countries attended the ceremony at the International Convention Centre.

Vietnam's admission ceremony as the 7th member of ASEAN took place on 7/28/1995.

Do Ngoc Son, Director of the ASEAN Department, was tasked with handing the Vietnamese flag to the ASEAN Secretary-General for the Bruneian honor guard to raise. The red flag with a gold star flew in the ASEAN sky, marking the moment Vietnam officially became the organization's 7th member.

Every time he recalls that special moment, Son still cannot hide his emotion. "Amidst the resounding national anthem, I felt very proud and thought to myself, 'Vietnam did it'," he recounted.

"So the period of hostility with neighboring countries has ended! Our nation shed so much blood to reach this day," Vu Khoan recalled his feelings at that moment.

Ambassador Do Ngoc Son recounts the day Vietnam joined ASEAN. Video: Anh Phu

Adaptation and affirmation

Integrating into ASEAN wasn't simply about walking through a door. It involved adapting to ASEAN's culture, principles, and working style. It was a period of both learning and asserting oneself, enabling Vietnam to quickly integrate into the regional "playing field" and subsequently rise to affirm its position.

Upon becoming an ASEAN member, Vietnam had to learn and become familiar with new working styles, commitments, values, and interactions.

"We used to joke that there were three additional criteria for joining ASEAN: knowing English, playing golf, and singing karaoke," Ambassador Son shared.

Not just Vu Khoan, many Vietnamese leaders and diplomats had to learn golf, a popular sport globally and within ASEAN at the time. Beyond exercise, ASEAN diplomats, politicians, and businesspeople viewed golf as a crucial way to connect with counterparts informally, addressing unresolved issues from official meetings.

"While riding in golf carts or playing golf together, they could discuss matters that couldn't be addressed at the negotiating table or even during dinners," Son explained. "We had to know how to play golf so that when sensitive, delicate issues arose that couldn't be discussed during negotiations, dinners, or meetings, we could take each other golfing."

In his book "Stories of Diplomatic Missions in the Era of Integration," Ambassador Nguyen Duy Hung recounted that in 1996 or 1997, during discussions on the Draft Joint Communique of the ASEAN Summit in Kuala Lumpur, some points remained unresolved and required reporting to the ministers for instructions.

However, that afternoon, the ministers were all participating in a golf tournament followed by a dinner reception, leaving no time to review the emerging issues in the Draft Joint Communique, a document scheduled for approval the following morning.

Around 6 PM, the ministers returned to the hotel, chatting cheerfully about the afternoon's golf game. Ambassador Hung and the Vietnamese delegation were anxious, unsure if the ministers had forgotten about the Joint Communique, as it contained a few unresolved issues related to Vietnam.

"Members of our delegation greeted Minister Cam and, seeing him smiling brightly, quickly asked about the Joint Communique to prepare accordingly. Minister Cam simply said, 'It's all done'. It turned out the ministers had discussed and agreed on everything on the golf course," Hung recounted.

Malaysia would revise the draft, and the ministers would approve it during the evening reception. "Everyone breathed a sigh of relief," Hung said.

Besides golf, ASEAN officials also maintained another form of relaxation after long, tense meetings: karaoke.

"After each foreign ministers' meeting, all ASEAN foreign ministers and their counterparts from the 10 dialogue partners would take the stage to perform karaoke and dance," Ambassador Son said. "This enhanced bonding and camaraderie, potentially facilitating informal discussions at the working level."

|

Foreign Minister Nguyen Manh Cam speaks at the 28th Annual ASEAN Foreign Ministers' Meeting on 7/29/1995, one day after Vietnam became the bloc's 7th member. Photo: TTXVN

In the 30 years since joining, diplomats have laid the groundwork for Vietnam's position within ASEAN. From initial reservations and apprehensions, Vietnam gradually became an active, proactive, and effective member.

Murray Hiebert, senior expert on Southeast Asia at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) in the US, likened Vietnam's efforts to open the door to ASEAN 30 years ago to "the blind men and the elephant".

"Vietnam entered the room, not knowing what the ASEAN 'elephant' was like. They needed time to 'warm up' and get acquainted, but they quickly became a key member of the Association," Hiebert told VnExpress.

Malaysian Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim also described Vietnam's three decades in ASEAN as an "impressive journey", emphasizing that the bloc's 7th member is now an "indispensable pillar".

Within the ASEAN family, Vietnam has truly found trust and strong bonds, assessed Deputy Prime Minister and Foreign Minister Bui Thanh Son. Vietnam is proud to participate in and contribute to ASEAN's milestones, from realizing ASEAN-10, signing the ASEAN Charter, establishing the ASEAN Community, and most recently adopting the "ASEAN 2045: Our Shared Future" document.

The position Vietnam holds in ASEAN today is partly due to the quiet efforts of its diplomats. The red flag with a gold star flying alongside the ASEAN and other nations' flags is not just symbolic; it represents a proud history of the nation's rise.

"Joining ASEAN not only ended the period of isolation but also marked a historic milestone, ushering in an era of active and proactive international integration for Vietnam," affirmed Ambassador Nguyen Trung Thanh, former Head of Vietnam's SOM to ASEAN from 2004 to 2007.

Thanh Tam - Thanh Danh