Thailand is reeling from a scandal involving monks and a 35-year-old woman named Wilawan Emsawat, also known as Sika Golf or Miss Golf. Authorities have identified at least 8 monks romantically linked to Miss Golf, with at least 15 having transferred money to her over several years.

The number of monks implicated in the scandal has risen to over 25. Among them, Theppatcharaporn, abbot of Wat Chujit Thammaram temple in Ayutthaya province, admitted to transferring nearly $400,000 to Miss Golf.

|

Monks pray during an alms giving ceremony at Wat Phra Dhammakaya temple in Pathum Thani province, north of Bangkok, in 2015. Photo: Reuters |

Monks pray during an alms giving ceremony at Wat Phra Dhammakaya temple in Pathum Thani province, north of Bangkok, in 2015. Photo: Reuters

Amid public outcry, Thai authorities on 13/7 released bank statements from temples nationwide, revealing over $11 billion held in temple accounts. This has raised questions about the management of these substantial funds.

In 2019, the National Office of Buddhism recorded 41,310 temples across Thailand. Monks rely mainly on alms and donations. Donating to temples is a deeply ingrained cultural practice in Thailand, seen as a way to earn merit for the next life and accumulate good karma more effectively than through charitable organizations or social work.

Research by the Thailand Development Research Institute (TDRI) indicates that each temple receives an average of 3.2 million baht (nearly $100,000) annually in donations. In 2018, total donations reached approximately $1.6 billion.

The Thai government allows full tax deductions for religious donations, incentivizing contributions from businesses and wealthy individuals. Some donate hundreds of millions of baht, even gold bars, at a time.

Thus, total donations can reach hundreds of millions, even billions, of USD annually. Nominally, these funds are for temple renovations, religious ceremonies, and offerings.

Beyond public donations, temples generate income through various means: renting property, selling entrance tickets, and operating parking lots. Some popular international pilgrimage sites even have their own TV channels to promote tourism.

Many Bangkok temples own prime real estate, profiting from services like hosting night markets, flower markets, and parking.

Another significant revenue stream comes from amulets. Temples produce amulets for sale or rent, ranging from a few hundred to millions of baht each, generating billions of USD annually.

Furthermore, Thai temples receive government funding for renovations, Buddhist education, and promoting Buddhism. Budget Bureau data shows that from 2013 to 2019, the state provided an average of $92.4 million yearly in temple subsidies, peaking at $144 million in 2016-2017.

These factors contribute to the accumulation of vast sums. However, abbots generally cannot authorize expenditures exceeding 90,000 baht (nearly $2,800) without higher approval.

The Supreme Sangha Council (SSC) established spending guidelines in 2014, requiring SSC approval for expenditures over $15,400. However, implementation is challenging due to a lack of standardized accounting and internationally recognized auditing. Consequently, most funds are deposited in banks, accruing compound interest and accumulating into assets exceeding $11 billion, rivaling the GDP of some small nations.

|

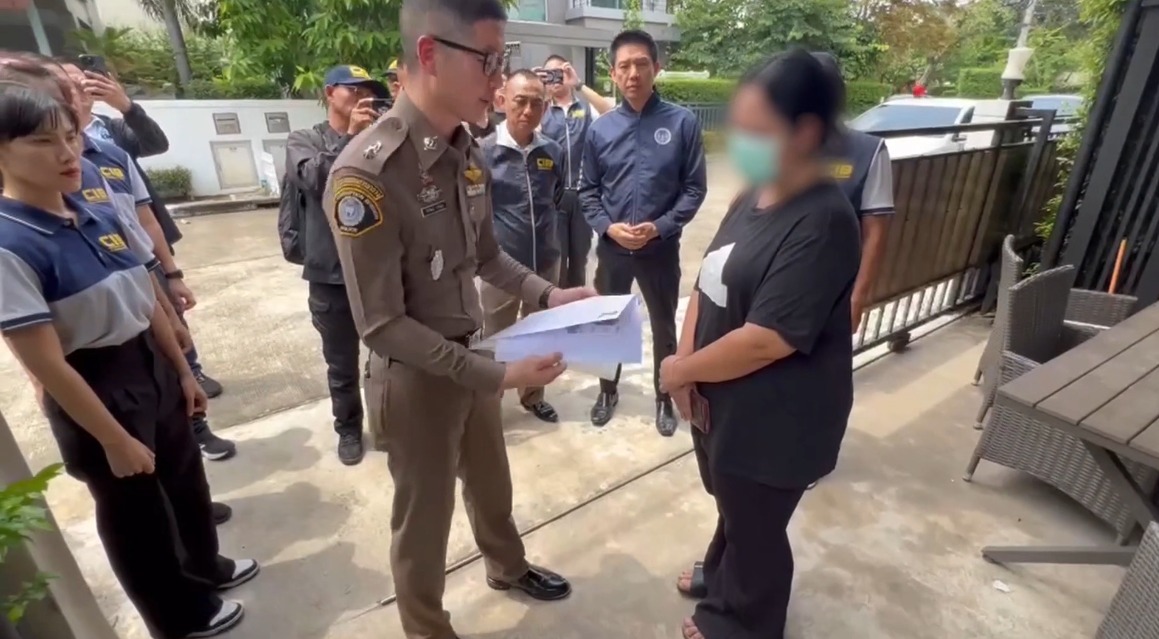

Thai police read the arrest warrant for Miss Golf on 15/7. Photo: TNA |

Thai police read the arrest warrant for Miss Golf on 15/7. Photo: TNA

Despite these holdings, a recent TDRI report highlights significant loopholes in temple financial management. The lack of oversight and transparency creates opportunities for corruption and money laundering, eroding public trust in Buddhism.

The TDRI cited several cases, including the 2014-2018 temple maintenance fund kickback scandal. Investigators uncovered corruption among National Office of Buddhism (NOB) officials who embezzled over $8 million by demanding kickbacks from temples receiving state subsidies.

Other notable cases include the monk Nen Kham, who solicited donations for a jade Buddha statue and hospital but used the funds for personal expenses, and the former abbot of Wat Rai Khing, accused of embezzling over $9 million from temple accounts for online gambling.

Such incidents raise concerns about temples being used as fronts for financial misconduct.

Public concern stems from the lack of transparency and potential for abuse in temple budget allocation, compounded by the absence of independent audits and public disclosure.

While temples are required to submit monthly financial reports to provincial Buddhist offices, the TDRI found inconsistent accounting standards. Most temples use cash ledgers without proper reconciliation or monthly categorization.

Furthermore, less than half submit reports on time, and expenditure information is rarely publicized, whether through notices or websites.

Thai authorities lack personnel specialized in temple finance oversight, and the NOB's supervisory capacity is considered weak. Power remains concentrated with abbots, and temples often resist reforms.

The TDRI urges the government to implement measures to enhance financial transparency in religious institutions and restore public trust. Without effective controls and oversight, scandals like the Miss Golf affair are likely to recur.

Vu Hoang (Bangkok Post, National Thailand, AFP, Reuters)