In early August, negotiations among over 200 countries for a global plastics treaty stalled in Geneva, Switzerland.

Meanwhile, Carbios, a French company pioneering the use of bacteria in plastic recycling, has entered the recycled plastic fiber supply chain of tire giant Michelin. Carbios uses bacteria to break down plastic, resulting in a new material comparable in quality to virgin plastic.

Plastic-eating bacteria were first reported in a scientific journal in 2016 by scientist Kohei Oda, a professor at the Kyoto Institute of Technology (Japan), and his colleagues. The bacteria, named Ideonella sakaiensis, secretes an enzyme called PETase that digests plastic, producing ethylene glycol and terephthalic acid (monomers), the precursors for creating new, virgin-quality material. This method allows for infinite plastic recycling.

This discovery opened a new chapter in bacteria-based plastic recycling research. Current recycling methods are primarily mechanical, involving shredding and grinding, which degrades the plastic quality and limits the number of recycling cycles.

Since Oda's discovery, scientists, governments of developed countries, international organizations, and companies like Carbios have been promoting this method, hoping the advanced plastic recycling industry will reach 200 billion EUR (over 235 billion USD) by 2050.

However, a major challenge is the slow rate at which bacteria consume plastic compared to the rate of plastic consumption and disposal. According to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 2024, the world uses 435 million tons of plastic annually, mostly in packaging, construction, consumer goods, and textiles. This amount is projected to nearly double by 2040, generating over 700 million tons of plastic waste, primarily handled through landfilling, leading to environmental leakage.

In Oda's initial experiment, Ideonella sakaiensis took seven weeks to digest plastic at room temperature, too slow to impact the massive amount of plastic waste.

Over the past decade, scientists have worked to modify the bacteria's enzyme to accelerate the digestion process. Elizabeth Bell, a researcher at the US National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL) in Colorado, describes this process as "two steps forward, one step back" due to the difficulty of manipulating natural evolution.

Through mutations in various experiments, the bacteria's digestion time has been reduced to a few days or hours, and continues to decrease.

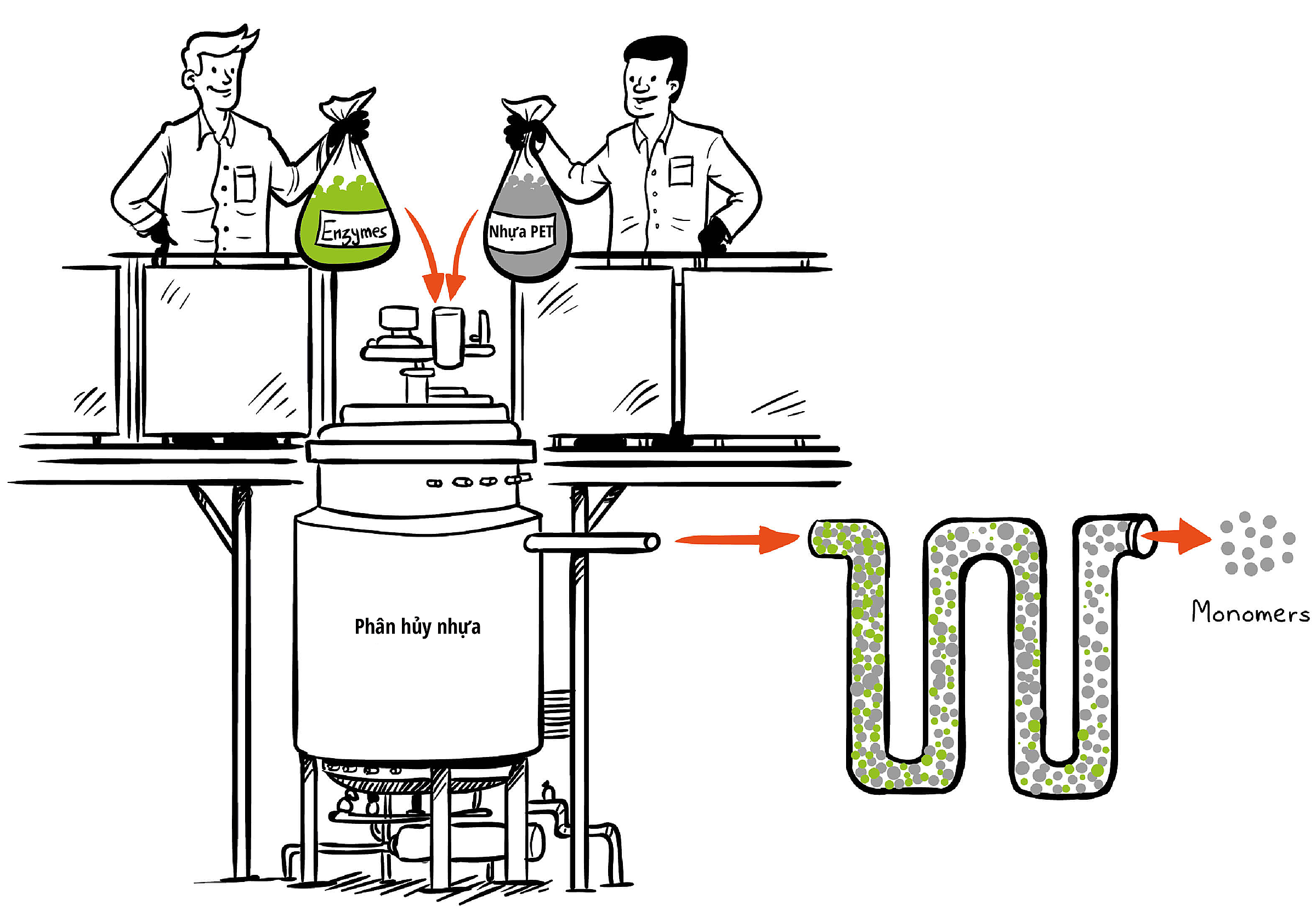

Carbios has achieved impressive results, breaking down plastic in 10 hours. This 2020 announcement was considered groundbreaking, as a plastic bottle could be transformed into new plastic precursors in just 10 hours by stirring it in an enzyme solution.

|

Carbios' enzymatic plastic recycling process. Source: Carbios |

Carbios' enzymatic plastic recycling process. Source: Carbios

A year later, they successfully processed 250 kg of PET waste daily. Backed by the EU and the French government, Carbios plans to open the world's first biological recycling plant with a capacity of 50,000 tons of PET plastic in France. This capacity is equivalent to recycling 2 billion plastic bottles, only 1/8,700 of the global annual plastic consumption. The plant was scheduled to launch this year but has been delayed due to lack of funding.

Another challenge is that bacteria can only consume certain types of plastic. While Carbios focuses on commercial-scale PET processing, research is ongoing for other plastics like PP (used in cups and baby bottles), PE (plastic bags and shampoo bottles), and PU (synthetic leather).

Besides bacteria that can recycle plastic, scientists have also found some that completely digest plastic, producing only biomass, CO2, and water. For example, the bacterium X-32, discovered by the Wyss Institute at Harvard University, can consume three types of plastic (PE, PP, and PET) but takes 22 months. In Serbia, mealworms are being trained to consume PE and PS plastics, producing only CO2 and water.

|

Mealworms consume plastic bags at a research facility of the Institute of Biological Research in Belgrade, Serbia, on 18/8. Photo: Reuters |

Mealworms consume plastic bags at a research facility of the Institute of Biological Research in Belgrade, Serbia, on 18/8. Photo: Reuters

Another obstacle to commercial-scale application is the concern about uncontrolled release of genetically modified organisms into the environment.

However, according to US scientist Elizabeth Bell, this risk is minimal. She cites Carbios, which uses enzymes rather than directly using bacteria or worms, making the process safer. The genetically modified bacteria used to collect enzymes are controlled within a laboratory environment.

"Scientists are working to develop safety mechanisms to ensure these bacteria cannot survive in nature," Bell added.

Scientists agree that addressing global plastic pollution requires a combination of recycling technologies. More importantly, during the global plastics treaty negotiations, experts recommended reducing plastic production and consumption.

The OECD suggests strict government policies like taxing or banning single-use plastics. Additionally, a circular plastic economy needs environmentally friendly packaging design and improved waste sorting before recycling.

Bao Bao (The Guardian, Hindu, HSBC)