Anas Baba, a radio producer for NPR, has lost a third of his body weight after nearly 21 months living amidst the conflict in the Gaza Strip.

Months of Israeli blockades on aid, coupled with current food distribution controls, have caused widespread hunger in the region. Health officials in Gaza report dozens of child deaths due to malnutrition.

Baba describes the people around him as weak and pale. They lean on walls and fences as they walk, or move in groups for support. Women and children frequently faint in the streets.

"For the past few months, I've been eating only one small meal a day, trying to stretch my food reserves. But three weeks ago, I ran out of basics like flour, lentils, and cooking oil," Baba said.

Street vendors sell necessities at exorbitant prices, around 100 USD per kilogram of potatoes, making them unaffordable for people like Baba. He has resorted to pickling watermelon rinds and spoiled potatoes to eat.

The only remaining option for many is receiving aid from the Gaza Humanitarian Fund (GHF), a US-based organization backed by the US and Israeli governments. It provides humanitarian aid to Gaza, bypassing traditional UN-led relief mechanisms.

The organization began operating in Gaza on 26/5, distributing hundreds of thousands of meals at three locations.

"But from the very beginning, we witnessed horrific scenes of people dying daily while trying to get food at GHF distribution points," Baba said.

Gaza health authorities and international medical groups report thousands of Gazans injured or killed by Israeli fire while seeking aid at GHF locations. Many return empty-handed, their food stolen by the crowds.

|

People line up for aid at a GHF distribution point in Gaza on the night of 24/6. Photo: *NPR* |

This hasn't deterred people from seeking aid. Baba explains that prolonged hunger impairs rational decision-making. "When your body and mind crave something, you fear nothing. You'll do anything for food," he said.

On the evening of 23/6, Baba and his cousin left Gaza City, walking for hours along the coast southward, risking everything to get food at a GHF distribution point in central Gaza. They packed a small backpack with water, bandages, and a first-aid kit. Others carried knives for self-defense against robbers, a common occurrence in famine-stricken Gaza.

Around midnight, a large crowd gathered along the road to the aid center, awaiting the signal to open. Reaching it meant crossing a military zone near the Netzarim corridor, largely under strict Israeli control and off-limits to Palestinians. Those crossing before the GHF opened risked being shot by Israeli soldiers.

The GHF has no fixed opening time. They open and close distribution points within minutes. Early arrivals get the most food, and supplies quickly run out. Many try to push ahead before opening, despite the risk of being perceived as a security threat by Israeli soldiers.

At 1:30 a.m. on 24/6, a car sped past with food strapped to its roof. Those inside yelled that the GHF had opened. The crowd started running toward the distribution point, with cars and motorcycles trying to push through.

"I saw someone get run over," Baba said.

Nearing the distribution point, they saw an Israeli tank. Its presence meant the GHF hadn't officially opened. But the crowd behind kept pushing, and the tank opened fire.

Baba and his cousin dropped to the ground, hearing gunfire and the screams of the wounded. People in the crowd cried out, "My brother is dead," "My friend is dead."

At 1:48 a.m., the gunfire continued in the pitch-black darkness. The crowd waited. At 2:00 a.m., the shooting stopped. "We took this as a sign the GHF had opened. I ran with the crowd toward the distribution point, stepping over bodies," Baba recounted.

In a later statement, the Israeli military acknowledged casualties from Israel Defense Forces (IDF) fire and said they were reviewing the incident. They denied intentionally firing on the crowd.

|

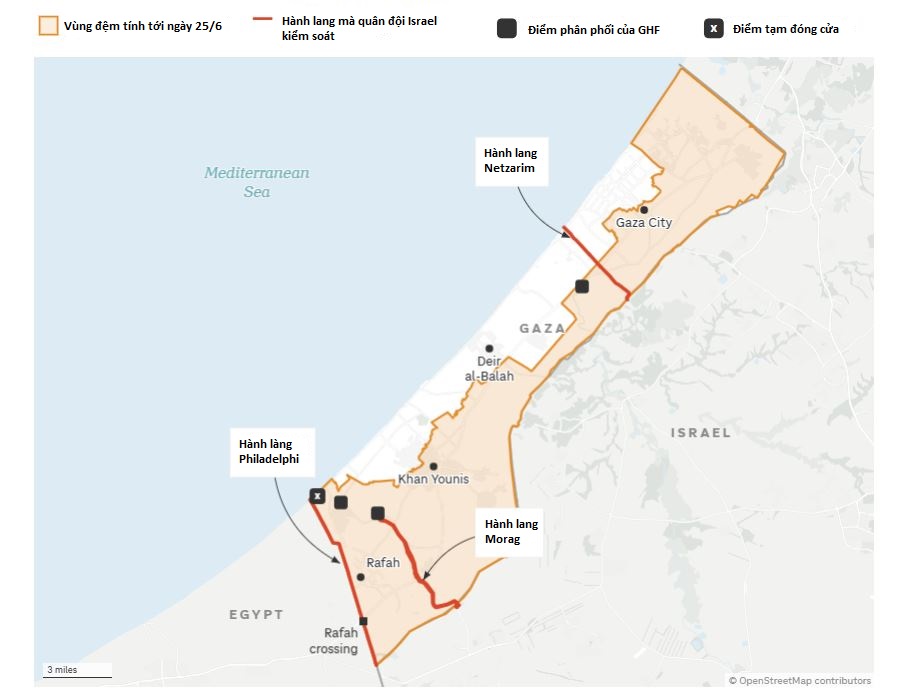

Locations of GHF distribution points in Gaza. Graphic: *NPR* |

The GHF distribution point finally opened. Baba saw hundreds of people pushing down the surrounding fence, trampling it to reach food boxes. He filmed the scene as thousands swarmed the boxes, grabbing as much as possible.

A sweating, angry woman in her 40s stood with her young son, brandishing two knives. She yelled at everyone: don't touch my son or my food. Law and order had vanished, replaced by the "law of the jungle."

Previously, hundreds of UN-run aid centers in Gaza provided flour and basic necessities. UN agencies would send text messages notifying people of their turn, and everyone would queue orderly.

Israel and the US accused Hamas of seizing UN aid, leading to the creation of the GHF to prevent this. But at the GHF point, Baba identified some people, based on their clothing, as Hamas members taking food.

"While filming, people told me to look at my forehead. Three green laser dots were on my head. Armed American guards at the GHF were aiming at me. Someone said in broken English, 'No filming'."

GHF officials acknowledge concerns about the unfixed opening times endangering Palestinians due to Israeli fire. They claim they're trying to prevent stampedes. The group says the Israeli military is working to ensure safe access, opening new roads and installing signs.

The GHF admits it can't fully screen out those connected to Hamas but claims to be preventing the militant group from controlling aid flow. They say they prohibit filming American contractors due to online threats.

A group of 170 human rights and aid organizations has called for an end to the GHF's distribution system due to the risks to Palestinians.

|

People gather at a GHF aid distribution point in Gaza on 24/6. Photo: *NPR* |

"At the distribution point, I pushed people aside and grabbed any food that fell on the ground. Cooking oil, biscuits, bags of rice torn open and mixed with dirt were all fine with me. It was food, and I could clean it later," Baba said.

Baba then struggled to pull his cousin free from the crush. Their next challenge was escaping safely with their food.

On their way back, four masked robbers with knives stopped them. They gave them two choices: hand over half their food or face the consequences.

"I offered them a little, but one started brandishing his knife. My cousin and I exchanged glances, threw the food bags at them, and ran," Baba said. "After escaping, I had enough food for about a week and a half, eating one meal a day."

Thuy Lam (*via NPR, AFP, Reuters*)