As President Donald Trump intensifies border control policies and immigration raids, even simple tasks like buying bread have become a source of anxiety for many Los Angeles residents.

Mayor Karen Bass recently visited a bakery in East Los Angeles one morning and found the doors locked, the people inside ignoring her knocks. It wasn't until she pressed her mayoral badge, displayed on her coat, against the glass that the owner opened the door.

|

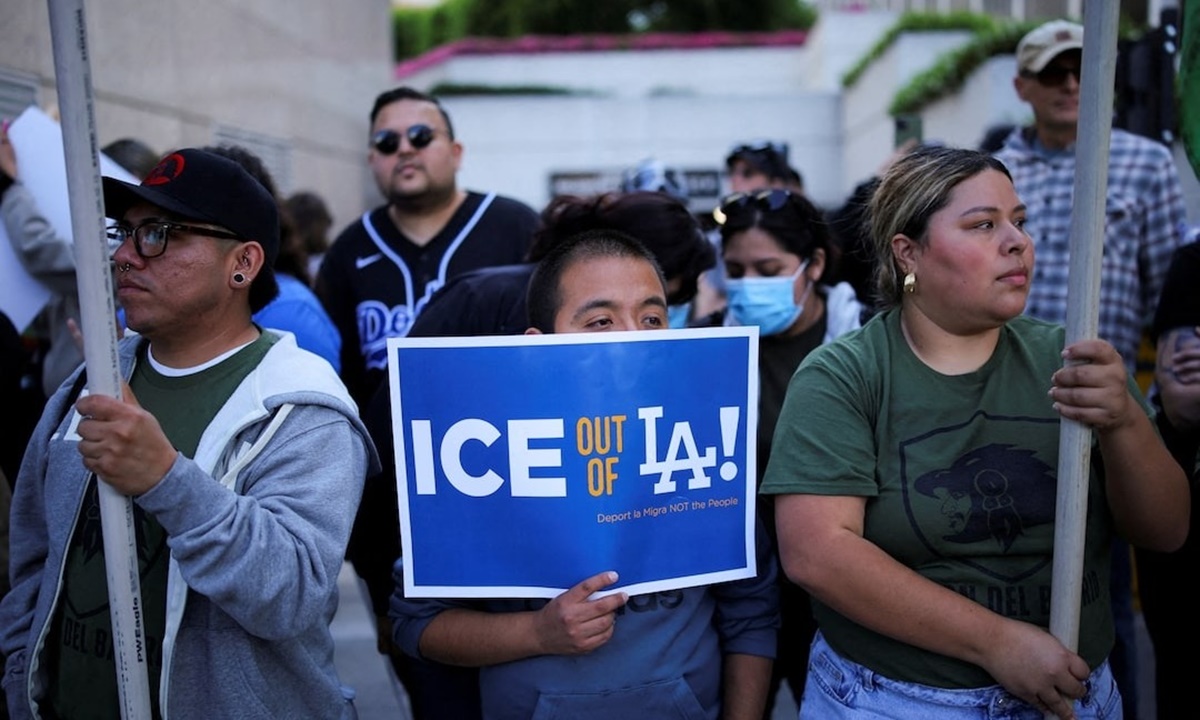

A protest against immigration raids in Los Angeles, California, in June. Photo: Reuters |

A protest against immigration raids in Los Angeles, California, in June. Photo: Reuters

"What saddens me is that people in this city are now afraid when they see a certain kind of vehicle," Bass said on 18/7 while visiting El Chapulin restaurant in Pico-Union, a predominantly Latino neighborhood, referring to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) patrol vehicles.

The initial tension of the immigration crackdown has subsided somewhat. About half of the National Guard troops, deployed by Trump to Los Angeles despite opposition from California Governor Gavin Newsom, have begun to leave. A federal judge temporarily barred ICE from using "roving patrols" to make arrests without probable cause that individuals are in the country illegally.

However, Los Angeles remains on high alert, worried about further crackdowns that many believe are inevitable.

Last month, ICE arrested over 2,000 people in seven Southern California counties, according to the Los Angeles Times. The Trump administration claimed those arrested had criminal records, but the newspaper reported that most had no prior convictions. Some legal immigrants and even U.S. citizens were also targeted.

"It's difficult because you don't know what's going to happen next," said Democratic Representative Mark Gonzalez, who represents Boyle Heights and other Latino communities in the city center.

Describing how her routine has changed in recent weeks, Dulce Maria Caro, manager of El Chapulin, said, "We don't go out with our families anymore. It's just work, home, work, home. It's like we're isolated."

"It's strange," added Jose Francisco, the restaurant owner's brother. "We live like prisoners now."

"And we feel alienated," Caro added.

During a visit to Bell, a city with a 90% Latino population southeast of Los Angeles County, Governor Newsom described the streets and shops as eerily deserted, "like a ghost town."

He told reporters about a local business owner complaining that the drop in customers was worse than during the Covid-19 pandemic. Another woman, a naturalized U.S. citizen, said the sound of helicopters during ICE raids terrified her.

"People are afraid to even go outside. We were there, and we saw not only empty stores but entire shopping centers with no one around," Newsom said.

The fear has even spread to those in high positions within the state government, such as former State Assembly Speaker Fabian Nunez.

"We all thought, 'Oh my God, it's not just the gardeners or the housekeepers who are being targeted,'" he said. "Many Latinos feel they can't leave their homes without their U.S. passports to prove their citizenship."

In last year's election, 30% of Los Angeles County voters cast their ballots for Trump, who campaigned on a promise of mass deportations. However, as ICE raids reach unprecedented levels, many of those voters have voiced their opposition.

"This has gone way beyond the initial promises, like 'We have to get rid of dangerous criminals, drug cartels, and gang members,'" said Sam Yebri, a lawyer and president of the centrist political group Thrive LA. "It's creating terrible economic consequences. I know many Trump supporters who don't agree with the raids, so I think the group that supports this approach is definitely a very small minority."

Department of Homeland Security spokesperson Tricia McLaughlin refuted reports that most of those targeted by ICE were not criminals. She said ICE raids have resulted in the arrests of "drug traffickers, MS-13 gang members, convicted rapists, convicted murderers, people you wouldn't want as neighbors."

|

Empty stalls inside El Mercadito, a Mexican marketplace in Los Angeles, in June. Photo: NPR |

Empty stalls inside El Mercadito, a Mexican marketplace in Los Angeles, in June. Photo: NPR

"Yet, Karen Bass, instead of thanking law enforcement, continues to smear and attack them," McLaughlin stated.

The pervasive fear among Latinos has deeply affected Mayor Bass. Her late husband was Mexican American, and many of her family members, including her deceased daughter, stepchildren, and grandchildren, are of Latino descent.

"Yes, this affects me directly, because I know all Latinos, anyone who looks Latino, are now under suspicion," she said, referring to a comment by Tom Homan, Trump's immigration advisor, that "looking a certain way" is enough for federal authorities to detain someone.

The federal judge who blocked the immigration raids in Los Angeles said administration officials had relied on improper factors like race, occupation, or regional accent in their sweeps.

McLaughlin, meanwhile, said it was a "despicable smear" to suggest that law enforcement targets individuals based on their skin color. "Legal status and criminal history, that's all we focus on," she asserted.

However, this does little to dispel the anxiety gripping many parts of Los Angeles.

"People don't feel safe," said Representative Gonzalez. "Daily life has been completely disrupted by these raids."

State Senator Sasha Renee Perez, a U.S.-born citizen, always carries her passport because her parents insist on it.

Tony Marquez, 72, a retired worker born in San Diego, used to carry only his phone while walking around his neighborhood. Lately, he also brings his driver's license for identification.

"Just in case," he said. "I'm a boring old man who likes to walk, living in Boyle Heights. For the first time in my life, I feel unsafe."

Hector Mata, 22, a U.S. citizen, avoids taking the bus for fear that ICE agents might conduct random checks on public transportation in Los Angeles. "I have brown skin, and that's all they need," he said, referring to how ICE agents conduct random checks and arrest people they suspect of being undocumented immigrants.

Since the immigration raids began this month, Los Angeles County's public transportation system has seen a 10% to 15% decrease in bus and train ridership. Latinos make up a significant portion of the system's passengers.

Todd Lyons, acting director of ICE, blamed politicians for stoking fear in the community about the enforcement of immigration laws.

According to Lyons, ICE agents have been carrying out their duties since before June, but are now being falsely portrayed as the cause of chaos. "That is absolutely false," he asserted. "It's the elected officials out there spreading this rhetoric, and they are the ones causing the fear."

In downtown Los Angeles, the Mexican marketplace on Olvera Street, a popular historic and tourist destination, has become increasingly deserted. Normally, visitors can easily find Hispanic snacks in Olvera. But on a recent afternoon, many shops were closed, and few people were around.

For undocumented gardeners, nannies, housekeepers, and day laborers, the fear of raids has made them wary of every move. Some have stopped working. Others only travel between their homes and their employers' homes.

|

Federal immigration agents near MacArthur Park in Los Angeles on 7/7. Photo: Los Angeles Times |

Federal immigration agents near MacArthur Park in Los Angeles on 7/7. Photo: Los Angeles Times

An undocumented woman who has been in the U.S. for over 20 years and works as a nanny said the fear of being randomly checked by ICE agents led her to skip her daughter's graduation ceremony. She agonized for days over whether to attend, but ultimately told her daughter, "I want to be here when you get back."

Tito Rodriguez, executive director of the Local Hearts Foundation, typically helps organize back-to-school events and Thanksgiving food drives in Long Beach and South Central Los Angeles. He has shifted his focus to distributing food to undocumented families too afraid to leave their homes to shop.

Rodriguez said he has been receiving messages from families across Southern California, from Long Beach near south Los Angeles to the San Fernando Valley further north, in recent weeks.

"There are so many messages, I can't handle them all," he said. "They're terrified. They don't dare go outside."

Christian Medina, 27, a grocery delivery driver living in Whittier, said even with U.S. citizenship, he limits going out unnecessarily. "Many people are afraid of being arrested by ICE, simply for stepping out of their homes," he said.

Vu Hoang (Politico, AFP, Reuters)