Do Ngoc Minh Luong, a Vietnamese computer science student, recently graduated from Seoul National University (SNU) – the top 1 university in the country. Despite holding a prestigious degree, Luong still faced visa issues during internships at two major corporations.

“At one company, I was their first foreign employee, so they took a lot of time to prepare sponsorship documents because they were unfamiliar with the process”, Luong recounted.

Rosa Haque, from Bangladesh, who graduated from Yonsei University and holds a master’s degree from KAIST (Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology), faced a similar situation. Additionally, she encountered obstacles because she did not find any job postings for international students on two popular platforms: Google and Naver. She often had to email human resources departments directly but received advice to apply through open recruitment processes alongside local candidates.

|

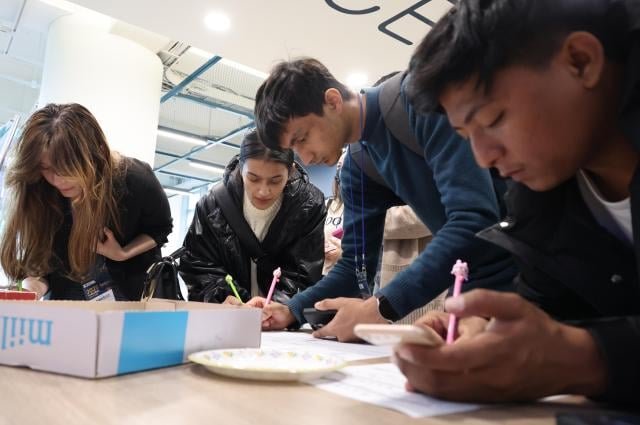

International students fill out job applications at the TU Global Job Fair in Busan, 11/2025. Photo: *Yonhap* |

According to data from the South Korean Ministry of Education, the number of international students who found employment in the country increased from 1,700 in 2018 to nearly 5,000 in 2024. However, the actual picture is less optimistic, as the total number of graduates also doubled during the same period. Consequently, the actual employment rate only slightly increased from 9,6% to approximately 13,8%.

Meanwhile, surveys indicate that 60-80% of international students wish to find employment in South Korea. This significant disparity is causing frustration for many.

Park, an employee at a company specializing in helping major South Korean corporations recruit foreign talent, noted that the number of jobs available for this group is sharply declining. If hired, positions are often at the executive level, rarely for new hires.

The already narrow path comes with numerous challenges. According to Rosa, Samsung, SK, and other companies all have their own standardized tests in Korean instead of English. Even South Korean applicants spend months preparing for these exams, so foreign applicants with limited Korean language proficiency face a significant disadvantage.

Beyond the language barrier, visa complexity is also a factor that makes businesses hesitant to hire international students, according to Hugo Adam, a French international student at SNU.

After graduation, international students must switch to a D-10 visa to stay for a one-year internship. However, to transition to an official employment visa (E-7) after this period, the application must match one of 90 job codes with extremely stringent requirements.

For example, a 450-page guide on visa requirements is available on the government immigration portal, but it is only in Korean. The section specifically for the E-7 visa is 105 pages long.

For businesses, sponsorship is often costly, administratively complex, and time-consuming. Therefore, many employers avoid hiring foreign candidates, unless for highly skilled positions or those requiring specific expertise.

This burden led Andrua Haque, Rosa’s twin brother, to an ironic decision when starting his own business. Despite being a foreigner himself, Andrua stated that he “would not consider hiring international students”.

Andrua added that in addition to meeting numerous paperwork requirements, companies must also meet specific ratios of South Korean to foreign employees. This means that for every foreign hire, his company would need to employ an additional South Korean staff member.

Responding to complaints from international student groups, the South Korean Ministry of Education stated it is aware of the situation and is working to improve it, through Korean language classes and by requiring local governments to demonstrate efforts to attract foreign talent to receive government support.

“But I have not seen any improvements so far”, Adam said.

Khanh Linh (Source: The Korea Herald, Inquirer)