|

Ho Chi Minh City’s 115 Emergency Center receives and processes an average of 100 emergency cases daily, transferring them to hospitals throughout the city. Nhan Dan 115 Hospital (right) is one of the facilities that receives the most cases. Photos: Hoang Viet and Khuong Nguyen |

On a weekend evening, the emergency department doors constantly swung open and closed. Wheels squeaked on the white tile floor, occasionally punctuated by a "thump" as a stretcher bumped against a door. Doctor Nguyen Ba Lan, the shift supervisor, frowned, his eyes glued to a stack of emergency medical records. One hand never left his pen as he scribbled information, while the other clutched a worn black phone, answering a call from a lower-level hospital requesting a patient transfer.

"We're full up here too," he said.

The patient needed a ventilator. Although 2 of the 6 ventilators in the emergency department's intensive care unit were available, Doctor Lan hesitated. Regulations stipulated patients could only stay in the emergency room for a maximum of 6 hours for initial treatment. Patients requiring long-term or specialized care needed transfer to a specialized department, but all were overflowing. Without the necessary equipment, maintaining vital signs would be difficult.

"If we accept a patient, we must provide proper care. But currently, the intervention rooms in other departments have no available beds, which increases patient waiting times and could cost them valuable time," Doctor Lan explained.

Ho Chi Minh City’s 115 Emergency Center receives and processes an average of 100 emergency cases daily, transferring them to hospitals throughout the city. Nhan Dan 115 Hospital (right) is one of the facilities that receives the most cases. Photos: Hoang Viet and Khuong Nguyen

Ambulances urgently delivered patients, their red lights blurring through the glass doors. The red lettering on the vehicles indicated the patients came from various sources: one-third from 115 ambulances, the rest from district and provincial hospitals.

Regulations required prior notification, mainly by phone, for inter-hospital transfers, especially for critical cases needing equipment like ventilators. Otherwise, ambulances directly transported patients to the nearest and most appropriate medical facility.

Over the past 20 years, the number of patients arriving at the department has more than tripled, averaging 300 cases per day. Previously, the primary source of patients was those arriving independently and transfers from lower-level facilities, with a low rate of pre-hospital emergencies. Since Ho Chi Minh City established the 115 Emergency Center in 2014, pre-hospital coordination and transfers have increased.

Between 2014 and 2020, the total number of emergency patients rose from nearly 7,000 to 32,000. In principle, regardless of overcrowding or equipment shortages, hospitals cannot refuse patients. This has become a bottleneck between pre-hospital and in-hospital emergency care.

The rising number of emergency cases has put immense pressure on the city's hospitals. While in-hospital doctors are stretched beyond their capacity, pre-hospital medical staff struggle to find places to transfer patients. Bottlenecks at the point of patient intake have become common.

Inside the intensive care unit, where the department's most critical patients are treated, 4 stretchers lay side-by-side. The smell of medicine hung in the cool air-conditioned air. Machines beeped rhythmically, connected to pale bodies by pale gray wires. Signs of life flickered across jagged waveforms and green and yellow numbers on patient monitors.

A middle-aged man with bloodshot eyes stood numbly watching his brother, entangled in wires, his prognosis uncertain.

Suddenly, the vital signs monitor beeped erratically, the blue waveform representing the heartbeat flattening, the numbers flashing red, sometimes dropping to zero. The man rushed to the door, shouting for a doctor. Within 10 seconds, a young doctor rushed in. Quickly pressing the emergency button to alert the team to the cardiac arrest, the doctor, with only one glove on, began chest compressions. The patient's abdomen rose and fell with each compression, amidst the long beeps of the machine and the sobs of relatives watching from the doorway. Less than 30 seconds later, another doctor and nurse arrived, one administering medication, the other taking over compressions, fighting to hold onto the fading hope of life.

2 minutes and 20 seconds later: "Not yet! (heartbeat)"

"Just got a pulse back!"

34 seconds later: "There it is, there's a heartbeat!"

|

The intensive care unit, where the department's most critical patients are treated, is also where life-and-death farewells frequently occur. This photo was taken at the emergency department of Nhan Dan 115 Hospital in 5/2025. Photo: Khuong Nguyen

Under the fluorescent lights of the emergency department, Doctor Lan and more than 10 doctors and interns, along with 15 nurses, constantly moved between stretchers and the administrative area. The low hum of activity was punctuated by ringing phones and calls for consultations. Stacks of green and red files, separated by internal and external cases, never seemed to diminish.

"At peak times, there aren't enough stretchers, patients sit in chairs waiting, while all 6 ventilators are occupied. Yet, ambulances continue to bring in critical patients, forcing medical staff to take turns manually ventilating," Doctor Lan recounted.

While hospitals are overcrowded or lack equipment, the "no refusal" policy in emergency care inadvertently places significant pressure on medical professionals and creates misunderstandings among patients.

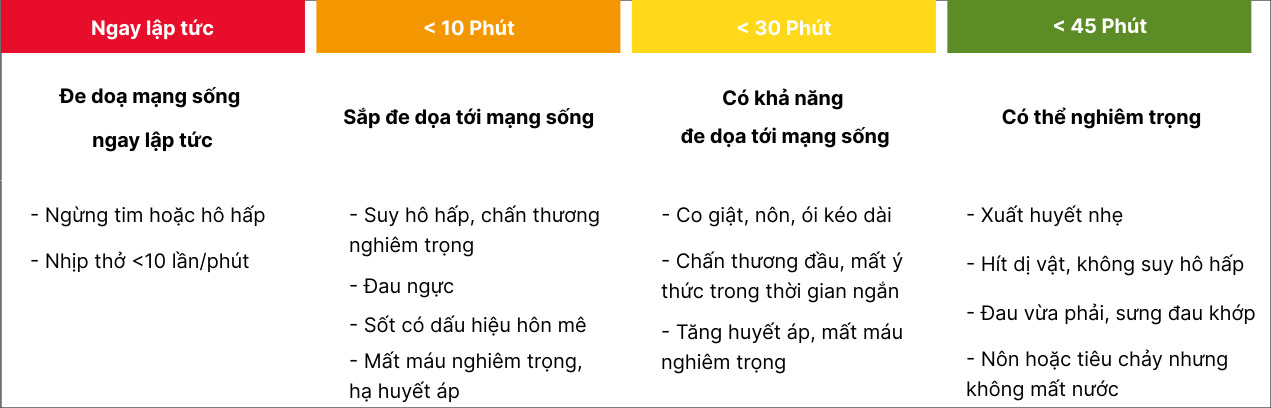

Doctor Khau Minh Tuan, head of the emergency department at Nhan Dan 115 Hospital, explained that a sudden influx of patients leads to congestion and prolonged waiting times. Emergency care is triaged based on the patient's condition, prioritizing the most critical cases. The more severe the illness and the greater the threat to life, the sooner the patient is treated, regardless of arrival time. Being the first to arrive doesn't guarantee being the first treated.

"Golden hour" treatment according to emergency triage levels:

|

Source: Circular 32/2023/TT-BYT detailing the Law on Medical Examination and Treatment. Graphics: Tam Thao

"This inherent conflict is difficult to resolve and increases negative feelings among relatives and patients," Doctor Tuan said. In his 20 years at the department, he has heard countless stories from colleagues about being chased or threatened with knives by patients' families.

To address the localized congestion, Doctor Tuan regularly communicates with the 115 Emergency Center to limit patient intake when the hospital is overcrowded or equipment needs repair.

"But that's based on personal relationships, not a shared coordination network," Doctor Tuan admitted.

A doctor at the emergency department of Nhan Dan 115 Hospital intubates a patient in 5/2025 (left). Patients in the emergency department are categorized by colored wristbands, with red indicating critical condition. Photo: Khuong Nguyen

According to Doctor Nguyen Duy Long, director of the Ho Chi Minh City 115 Emergency Center, few hospitals proactively report their status like Nhan Dan 115 Hospital. To optimize coordination, emergency teams need real-time information on the current capacity of local medical facilities. However, most pre-hospital teams remain in a reactive situation.

He gave an example of stroke diagnosis requiring a CT or MRI scan. However, if a hospital's equipment is malfunctioning and the 115 emergency team isn't informed, they might bring a patient there only to be refused, losing valuable time in transferring to another facility.

Doctor Do Ngoc Son, director of the Intensive Care Center at Bach Mai Hospital (Hanoi), having worked in emergency departments for over 20 years before specializing, recognizes the weak link between pre-hospital and in-hospital emergency systems. He believes current legal frameworks lack regulations for coordination between the two.

The concept of "pre-hospital emergency" was first recognized in the Law on Medical Examination and Treatment in 2023. Previously, the law lacked this designation, considering it simply as emergency care outside medical facilities. Doctor Son considers this legal recognition a step forward, but only a beginning.

"Connecting pre-hospital and in-hospital emergency care requires considering many factors, including specific legislation on pre-hospital emergency care," Doctor Son commented. "The relationship between in-hospital and pre-hospital emergency care remains loose and lacks binding regulations."

|

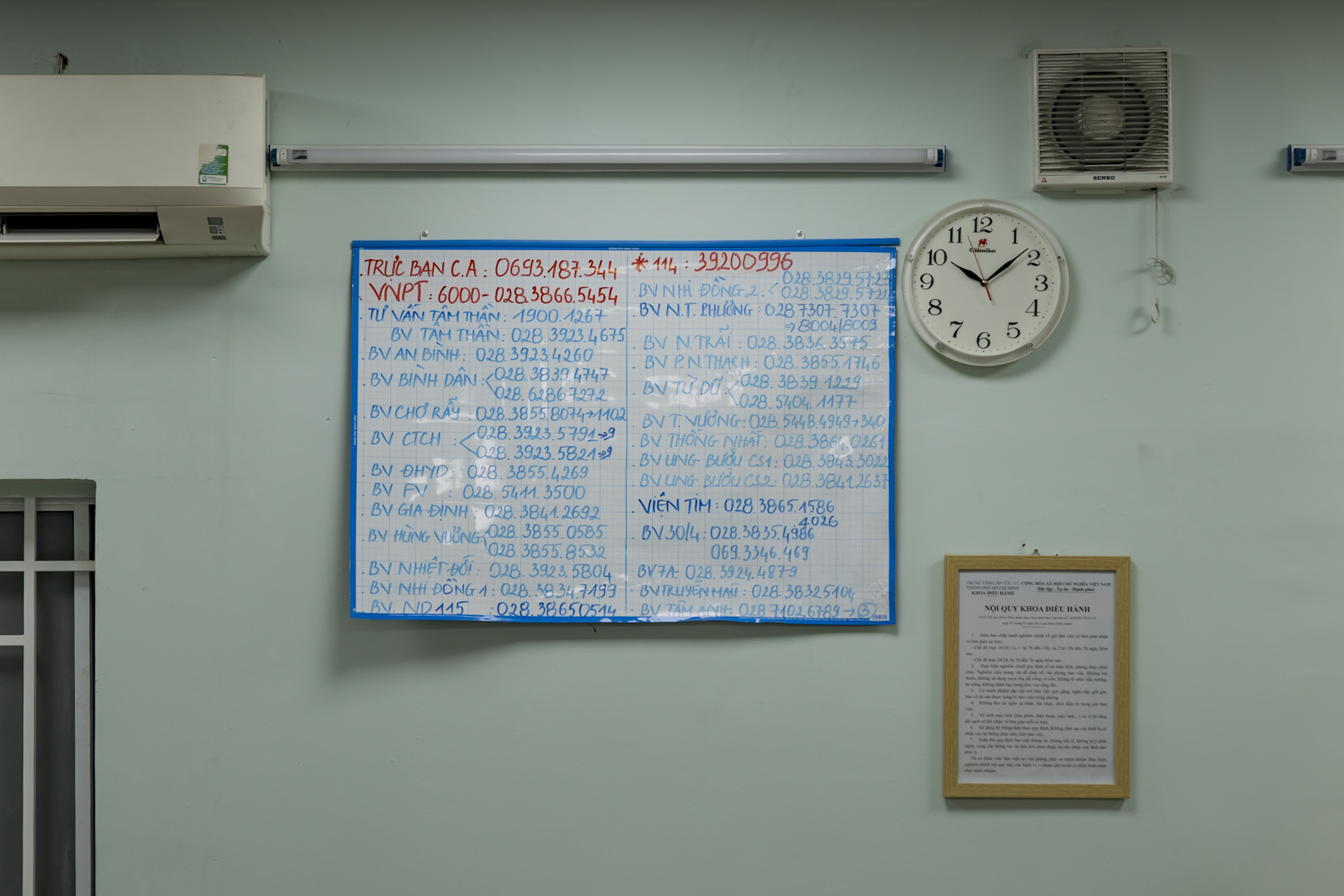

Phone numbers of hospitals and authorities are prominently displayed for emergency staff to contact them quickly. Photo: Hoang Viet

The satellite station link:

For over 6 years in pre-hospital emergency care, nurse Tran Duc Tri, from the emergency department at Le Van Thinh Hospital – one of the first satellite stations of the 115 Emergency Center – has often been torn between multiple critical cases.

The most typical pre-hospital emergency model in Vietnam involves an emergency center acting as a coordinator, with a network of satellite stations located in hospitals throughout the area. Pioneering cities like Ho Chi Minh City and Hanoi have adopted this model.

The pre-hospital emergency system operates through three main entities: the 115 Emergency Center as the primary coordinator; the emergency network within each hospital; and private medical facilities. Of the 45 satellite stations of the Ho Chi Minh City 115 Emergency Center, 42 are partnerships with emergency departments in public and private hospitals in the city, like Le Van Thinh Hospital.

Operators at the 115 Emergency Center (left) receive information, dispatch vehicles, and provide remote emergency guidance (left). Meanwhile, the pre-hospital emergency team contacts the family to verify the patient's condition, provides first aid instructions, and informs them of the estimated arrival time. Photos: Hoang Viet and Phung Tien

All calls to 115 in Ho Chi Minh City are received by operators at the 115 Emergency Center, who then triage and dispatch vehicles from the nearest station. Currently, 65% of emergency cases are handled by satellite stations.

After receiving a case, the satellite station contacts the caller, verifies the information, and advises on travel time. For less severe cases, they encourage patients to come to the hospital independently due to potential ambulance delays, especially over long distances or in traffic. However, not everyone agrees. In some cases, initially reported as severe and immobile, the patient's condition upon arrival is less critical than expected, with normal vital signs, allowing for independent travel.

While basing stations on the existing medical facility network is effective, it also has drawbacks due to uneven hospital distribution. Doctor Nguyen Duy Long points out that some large areas, like the former Can Gio district, have only one station.

The total staff, including doctors/medical assistants, nurses, and drivers, at satellite stations in Ho Chi Minh City is 692, nearly 5 times that of the 115 Emergency Center. Despite this seemingly high number, Doctor Long reveals that stations don't have dedicated pre-hospital emergency teams. Staff multitask, caring for in-hospital patients, transferring patients to higher-level facilities, responding to 115 calls, and handling the hospital's own emergency hotline. There are instances where, after contacting 4 or 5 stations unsuccessfully, the center is forced to dispatch its own vehicle, sometimes taking an hour to reach the scene.

"This is the challenge of handling both in-hospital and on-site emergencies," nurse Tran Duc Tri confided.

He explained that each pre-hospital emergency call can take up to an hour. When the department is less busy, it's easier to manage, but on busy days, he often has to interrupt tasks like drawing blood or administering IV fluids to respond to emergency calls. A shift with 5 nurses means those remaining must cover his duties when he and a doctor leave for a call.

He often has to decline calls from the 115 dispatch, but after 15-20 minutes, they often call back because they can't find another available satellite station. If he has managed to arrange his tasks and an ambulance is available, he will go; otherwise, he has to refuse again.

"What kind of emergency is this? Half an hour? I'll be dead by then," Nurse Tri recounted a common complaint from callers when he contacts them before dispatch.

"For me, it's not a top-priority emergency, but for the family, it is," he said.

According to Nurse Tri, sometimes while handling a non-urgent emergency case, a truly critical situation arises, such as a coma or traffic accident, but there's no team available. Typically, a shift only has one team for pre-hospital emergencies, unless the situation is extremely critical and the in-hospital department isn't overloaded, in which case another vehicle might be dispatched.

In addition, Le Van Thinh Hospital also receives numerous calls to its own emergency hotline. For example, in 2/2025, there were 48 calls, almost equal to the number from the 115 dispatch (55 calls).

Pre-hospital emergency care often operates under challenging and uncontrolled conditions, such as moving patients in confined spaces. Photos: Khuong Nguyen and Hoang Viet

According to Doctor Nguyen Duy Long, Vietnam has not yet implemented a tiered emergency response system based on call severity. For instance, the US uses a five-level system from delta to omega, where delta requires immediate dispatch with a specialized ambulance, while omega is the least urgent, sometimes only requiring advice, reassurance, or non-emergency transport. He notes that only 20% of calls to the Ho Chi Minh City 115 dispatch require immediate emergency response, while the remaining 80% can be delayed.

Another challenge faced by satellite stations is financial loss, including cases involving homeless patients or those without relatives, or when a dispatched vehicle arrives but the patient no longer requires emergency services. In the first 4 months of 2025, the loss rate at Le Van Thinh Hospital's satellite station was 37% of the 227 dispatched cases. At the Ho Chi Minh City 115 Emergency Center, the annual loss rate is under 10%.

Doctor Do Ngoc Son, director of the Intensive Care Center at Bach Mai Hospital, analyzes the core issue as how responsibilities and financial burdens are shared. When patients cannot pay, satellite stations might have to absorb the cost, while many are required to be financially self-sufficient.

"The current model is still based on voluntary sharing rather than a concrete system," he stated.

To mitigate financial losses, Doctor Long hopes for funding from sources like the Fatherland Front Committee, NGOs, or social insurance. Currently, only Da Nang (before merging) has a public ambulance service that doesn't charge fees, funded by the city budget.

"How can we ensure that people don't have to pay anything when they need emergency care?" Doctor Long questioned.

|

In addition to their medical duties, doctors in the emergency department must also handle paperwork, sometimes spending over 10 minutes completing a single file. Photo: Khuong Nguyen

To expand pre-hospital emergency coverage nationwide, Doctor Do Ngoc Son believes in establishing a dedicated law for pre-hospital emergency care. This law should specify investments in the 115 network and infrastructure for each administrative unit, outlining the responsibilities of involved parties and penalties for non-compliance.

"It's unacceptable that localities with higher budgets have investments and operational centers, while poorer provinces have privatized or non-existent 115 services," he said.

To connect pre-hospital and in-hospital emergency care, Doctor Khau Minh Tuan, head of the emergency department at Nhan Dan 115 Hospital, proposes a shared coordination model connecting hospitals with the 115 emergency service. This network shouldn't be limited to a single locality but should extend regionally to facilitate inter-provincial emergency care. This would allow 115 teams to check real-time bed availability and equipment capacity, especially for cases requiring ventilators, enabling more efficient and convenient patient coordination.

According to Doctor Nguyen Duy Long, this solution is part of Ho Chi Minh City's plan to develop its pre-hospital emergency system by 2030, announced in 3/2024. However, with limited resources, implementation will be gradual.

A large-scale coordination system connecting multiple entities requires digitalization of medical data. This process has been accelerated recently, including updates on hospital overcrowding and the creation of a medical expert database. For critical cases, pre-emptive connection with specialists allows for joint analysis, planning for equipment needs, and selection of appropriate transfer locations.

Since July 1st, Ba Ria - Vung Tau and Binh Duong provinces have merged into Ho Chi Minh City. These provinces lack dedicated 115 Emergency Centers, with emergency services primarily handled by a few hospitals.

Doctor Long states that initially, the 115 numbers from all three areas will be merged under the management of the Ho Chi Minh City 115 Emergency Center. Residents of the former provinces won't need to dial area codes. Simultaneously, the 115 Center will rapidly expand its satellite station network in the newly incorporated areas.

In the long term, the 115 Center will reassess station placement and ambulance parking, expanding beyond medical facilities to include high-traffic areas like shopping malls and pedestrian streets.

"Once the bottleneck between in-hospital and pre-hospital care is resolved, a widespread satellite station network will reduce emergency response times and offer better chances of survival to more people," Doctor Long concluded.

|

Medical staff from Ho Chi Minh City’s 115 Emergency Center reassure patients, helping them stay calm during the journey from home to the hospital. Photo: Hoang Viet

Content: May Trinh - Phung Tien - Le Phuong

Photos: Khuong Nguyen - Hoang Viet

Part 1: Behind the Emergency Call Part 2: Emergency Care Under Pressure Part 3: 115 Medical Staff: 'We're Not Just Transporters' Part 4: A Tenuous Connection: Bridging the Gap Between Pre-hospital and In-hospital Emergency Care |