|

The nerve center of Ho Chi Minh City's ERC is located at 266A Ly Thuong Kiet (formerly District 10), coordinating a network of 45 satellite stations across the city. Photo: Hoang Viet |

"Administer noradrenaline via an electric syringe pump," Dr. Tan commanded. The drug is crucial for raising dangerously low blood pressure.

In the dim light, the ambulance screeched to a halt. One nurse rechecked the patient's blood pressure while another prepared the electric pump to administer the precise dosage of the vasoactive drug. Every action was executed within minutes.

"We must get to a hospital as quickly as possible," Dr. Tan declared firmly.

Instead of An Binh Hospital, their original destination, the ambulance rerouted to Nhan Dan 115 Hospital, the closest facility.

Inside the 5-square-meter ambulance, 31-year-old Pham Dinh Duy from Tan Phu District shook his mother's hand as she lay on the stretcher, but she didn't respond. Her heartbeat, blood pressure, and breathing were faint. This was Duy's 4th time riding in an ambulance with his mother, and the most terrifying. On the previous three occasions, she had been conscious and able to talk.

Seeing her condition, Dr. Tan grew anxious. The team worked tirelessly to stabilize her vital signs until they reached the hospital. Getting her to advanced care within the golden hour was her best chance of survival.

Her deteriorating condition indicated an immediate life-threatening situation requiring specialized intervention within 10 minutes. Administering noradrenaline was the most effective action the pre-hospital team could take.

The race against time

In the 50-square-meter room at the ERC, dispatchers' eyes were glued to screens, ears to phones, and hands searching for locations on maps. They were the first responders, initiating the race to save lives.

"What's wrong with the patient, sir?" a dispatcher asked, trying to gather every piece of information from the caller. "Is the patient conscious and responsive?"

Duy frantically relayed fragmented information, repeatedly pleading for an ambulance.

On the computer screen, red, yellow, and green bars appeared, representing the urgency of each case. Duy's mother was immediately categorized as red—the highest priority—due to her age, recent surgery for a fractured leg, and underlying health conditions.

|

The 4-person emergency team, consisting of a doctor, two nurses, and a driver, reached the patient's home. Due to the cramped room, the stretcher had to be left in the common walkway. Photo: Khuong Nguyen |

The nerve center of Ho Chi Minh City's ERC is located at 266A Ly Thuong Kiet (formerly District 10), coordinating a network of 45 satellite stations across the city. Photo: Hoang Viet

The dispatch bell rang as the call ended, alerting Dr. Tan and his team. Within 5 minutes, they had gathered their equipment and were en route.

With 5 years of experience, Dr. Tan had anticipated a difficult situation, but the reality was worse than he'd imagined.

Eight minutes later, the ambulance stopped at an alley on Thoai Ngoc Hau Street (formerly Tan Phu District), where the family was waiting. Without a word, the team sprang into action. The driver grabbed the stretcher, the doctor and nurse carried the equipment, and they hurried into the musty corridor of the workers' housing complex.

The 4-person emergency team, consisting of a doctor, two nurses, and a driver, reached the patient's home. Due to the cramped room, the stretcher had to be left in the common walkway. Photo: Khuong Nguyen

The 15-square-meter room, cluttered with belongings, left only a narrow passage. Dr. Tan and his team had to maneuver carefully to reach the patient lying on the mezzanine floor.

In the dim light, 27-year-old nurse Nguyen Thanh Thao Nhi struggled for 15 minutes—three times longer than usual—to find a vein for an IV line. Years of treatment had left the patient's veins fragile and collapsed.

"Her veins were as thin as threads," Nhi said.

Duy stood outside, watching the team, wincing each time his mother cried out in pain.

"Hang in there, ma'am. It won't hurt much longer," the nurse reassured her, holding her hand.

Still conscious, the patient reacted strongly, scolding the nurse, "You're hurting me! I didn't say anything before, but now you're hurting me again."

"The situation became quite chaotic," Duy recounted.

While the nurse worked on the IV, Duy explained to Dr. Tan that his mother's symptoms had started in the late afternoon, but he hadn't called 115 until after midnight because she didn't want to go to the hospital. She was recovering from surgery for a fractured femur and had a history of lung infections and obesity.

The cramped room made treatment difficult. Every movement could cause pain to the patient's swollen, recently operated legs. Photo: Khuong Nguyen

After much effort, the team managed to establish one IV line instead of the planned two, just enough to administer medication during transport. After placing an oxygen mask on the patient, Dr. Tan checked her EKG and vital signs before moving her to the ambulance.

"Her condition is still critical," he informed Duy, who anxiously awaited news. All signs pointed to a grim prognosis.

Nurse Nhi recalled that the team still held out hope because the patient responded when called by name. In many cases, patients are unresponsive and only react to painful stimuli. The team's primary goal was to keep her vital signs stable until they reached the hospital.

At 1:42 a.m., the ambulance set off for An Binh Hospital (District 5) at the family's request, as that was where her health insurance was accepted.

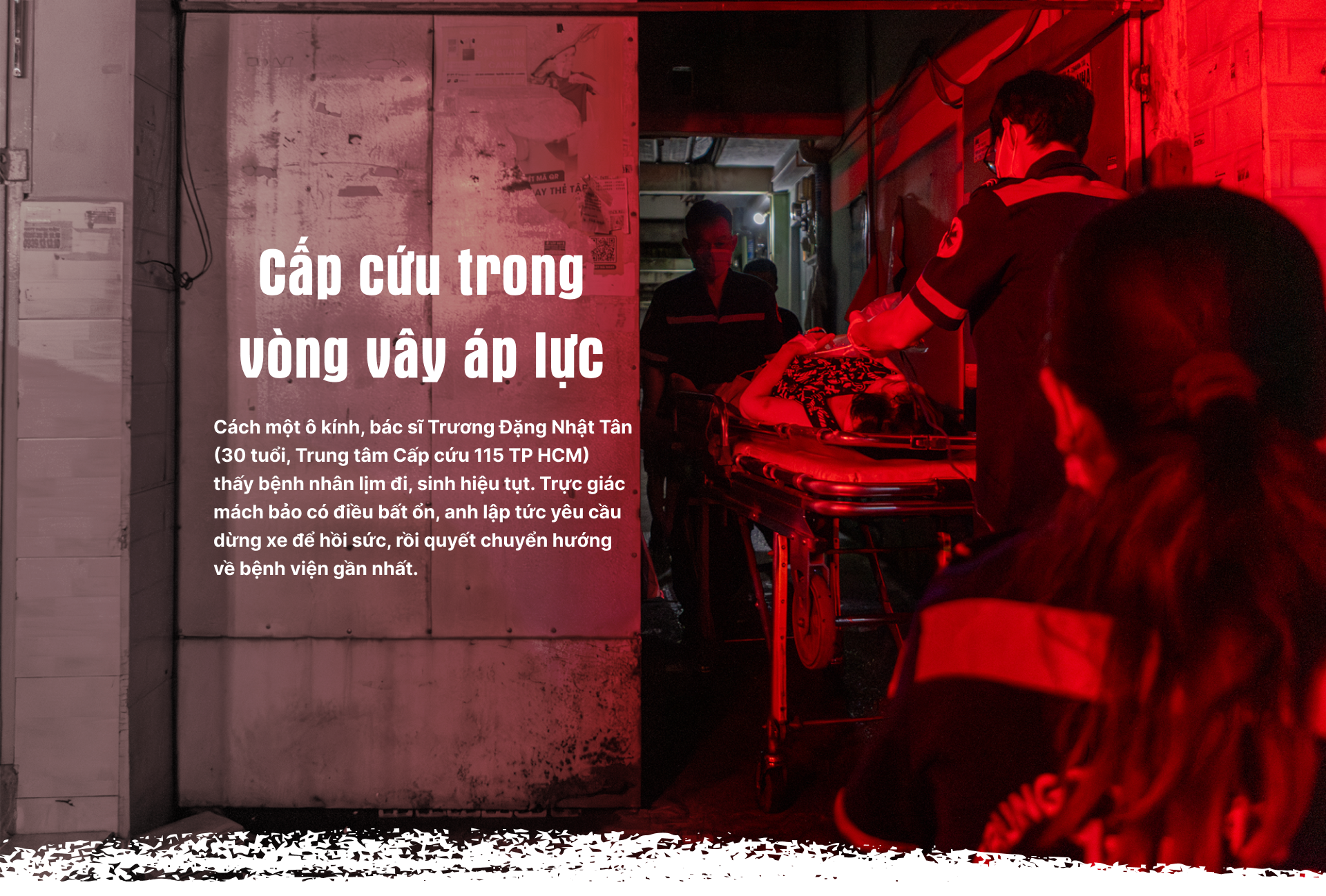

Just 3 minutes into the journey, Dr. Tan noticed the patient slipping into unconsciousness. Duy called out to her, but she didn't respond. Sensing trouble, the doctor ordered the driver to stop and recheck her vital signs.

Seeing her rapid decline, he made the decision to reroute. He called Nhan Dan 115 Hospital, warning them of a possible pulmonary embolism, which could cause a rapid drop in blood pressure and sudden death without immediate intervention.

As the team worked, Duy struggled to understand what was happening. He worried about whether his mother's health insurance would be valid at Nhan Dan 115 Hospital instead of An Binh.

"The most important thing right now is to get her to a hospital. Without timely in-hospital intervention, such as restoring blood flow, all our efforts will be in vain," Dr. Tan explained.

The nurse used an electric syringe pump to continuously administer noradrenaline to the patient, maintaining her vital functions. After 50 minutes of pre-hospital care, she was transferred to Nhan Dan 115 Hospital. Photo: Khuong Nguyen

At 2:00 a.m., the ambulance arrived at Nhan Dan 115 Hospital. The stretcher was rushed directly to the ICU.

Over the next three hours, she went into cardiac arrest three times. When her heart restarted after the first two rounds of CPR, the medical staff knew her body was failing. Hope was fading. The doctor called Duy aside, updated him on the situation, and advised him to prepare for the worst.

|

Duy sat in the hallway of the emergency department at Nhan Dan 115 Hospital, waiting for the ambulance to take his mother home. Photo: Khuong Nguyen

Duy sat silently outside the ICU, his gaze vacant. After a long pause, he decided to sign the discharge papers to take his mother home.

Under the cold fluorescent lights, Duy clutched his mother's blanket. Beside him lay a bag of diapers, medical records, and the health insurance card he had purchased that morning. As he waited for the discharge procedures, his mother's heart stopped again. The emergency room bustled with activity, but Duy remained numb, facing the reality of impending orphanhood.

"My mother is gone," he called his relatives, his voice cracking with each mention of "mother," replaying in his mind everything he could have done differently.

"We took too long at home… touched her injured leg…" he muttered.

6:00 a.m.—the time he and his mother usually woke up. He often made her breakfast and had planned to buy her a bowl of pig's organ porridge that day because she had mentioned craving it. Now, that opportunity was lost.

During the 30-minute drive home, Duy felt like a sleepwalker. He continued to manually pump the bag valve mask, desperately clinging to the last vestiges of his mother's breath.

"This is her last ambulance ride," he whispered, holding her cold hand.

Duy on the ambulance ride taking his mother home. Video: Khuong Nguyen

Emergency care within the golden hour is a race against time. Emergency responders face immense pressure, not only from their medical duties, but also from countless variables beyond their control.

When the lifeline is blocked

As the emergency call came in, 29-year-old Dr. Nguyen Hoang Tu Minh and his team received their dispatch orders. Since all 5 satellite stations near Go Vap District were busy, they had to travel nearly 12 km at 5:45 p.m., right during rush hour.

Dr. Minh worried about the elderly patient with multiple underlying health issues and difficulty breathing, recognizing the need for swift action.

The ambulance driver blared the siren but struggled to navigate the narrow, rush-hour traffic. Video: Hoang Viet

"She's stopped breathing," a woman's distraught voice informed the doctor over the phone.

The ambulance had been on the road for 15 minutes but was still almost 9 km away. Determining that the patient was in cardiac arrest, Dr. Minh immediately guided the family through CPR over the phone. He also contacted the dispatcher to continue monitoring and instructing the family in basic life support—the only option until the team could arrive.

Traffic worsened due to rush hour and light rain, slowing all vehicles. The driver honked incessantly, but the ambulance inched forward through the crowded streets. Inside, the team grew increasingly anxious. Every delay diminished the patient's chances of survival.

40-year-old driver Dam Le Thien An gripped the steering wheel, his eyes scanning for openings in the traffic.

"Sometimes, you just have to endure it; there's nothing else you can do," An said. "Often, people don't respect ambulances. They don't move when you honk. We have to roll down the window, bang on their cars, and yell, 'Make way, make way, emergency, emergency!'”

At 6:30 p.m., 45 minutes after the initial call, the team finally reached the patient's home.

|

Dr. Tu Minh and the emergency team took turns performing CPR. Photo: Hoang Viet

"Her prognosis is very poor," Dr. Tu Minh informed the family after checking her vital signs.

The patient's pulse and blood pressure were zero, her pupils dilated and unresponsive to light. Her blood oxygen saturation (SpO2) was only 65-70%, 25-30% below normal.

For 30 minutes, the team performed CPR, bag-valve mask ventilation, and administered adrenaline every 3-5 minutes—a last-ditch effort to revive her heart. But the EKG monitor showed only a flat line.

All attempts to save her were futile.

After hearing the doctor explain that there was no chance of recovery, the family nodded silently. They agreed to stop resuscitation and remove the endotracheal tube.

"She started having trouble breathing around 4:00 p.m. We didn't get the call until almost 6:00 p.m. But the traffic was so bad, and the distance so far…," Dr. Tu Minh said, her voice trailing off. Once again, she faced the reality that the line between life and death is often beyond a doctor's control.

Dr. Nguyen Hoang Tu Minh (29 years old, left) used a bag valve mask, striving to save the patient. Photo: Hoang Viet

Before its merger, the ERC served the entire Ho Chi Minh City area, with a population of over 13 million. The average response time for ambulances (excluding satellite stations) was 16 minutes, ranging from 5 minutes to 155 minutes.

According to Dr. Nguyen Duy Long, Director of the ERC, the 16-minute response time aligns with World Health Organization (WHO) recommendations. However, for immediately life-threatening cases like cardiac arrest, the target response time is 8 minutes or less. This standard has been adopted by many countries with pre-hospital emergency systems, including Thailand, the UK, and the US.

A study by Siriporn Damdin of Ramathibodi Hospital (Thailand) and colleagues, involving 5,433 out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients from 2019 to 2023, showed that response times under 8 minutes increased survival rates by 2.31 times at the scene, 1.76 times upon hospital admission, and nearly 2.09 times upon discharge.

Compared to other major cities, response times in Ho Chi Minh City are often longer, especially in Can Gio and Cu Chi (formerly) districts, where transport can take over an hour due to distance and traffic congestion.

Dr. Long noted that the demand for pre-hospital emergency services is concentrated in central districts like Districts 1, 3, 10, Binh Thanh, and Tan Binh (formerly), which have high population densities and numerous tertiary hospitals. These areas also experience frequent and severe traffic jams, especially during peak hours.

In suburban areas, the current emergency station network is limited, hindering optimal response times. Satellite stations are primarily located at public hospitals, but hospital distribution is uneven. For example, Binh Chanh District only has Binh Chanh Hospital and Nam Sai Gon Hospital (bordering former District 8), while Can Gio District has only one facility providing pre-hospital emergency care.

Furthermore, Dr. Long pointed out the lack of a tiered emergency response system to differentiate between urgent and non-urgent cases. All calls to 115 are dispatched if resources are available, even for non-critical situations like stomachaches, fatigue, and dizziness. This stretches resources thin, impacting response times for more serious emergencies.

On the return trip, the nurse sat slumped against the ambulance wall, playing pop music on her phone, staring blankly ahead. Beside her, the student intern leaned silently against the seat, speechless.

The sounds of the siren and music filled the ambulance, masking the team's silence.

"Families place all their trust in us. The saddest thing is when we can't fulfill that trust," Dr. Tu Minh confided.

|

Dr. Tu Minh offered condolences to the family before completing the death certificate. Photo: Hoang Viet

Beyond the external factors they can't control, emergency teams also face "battles" unrelated to medical expertise, stemming from patients and their families.

Non-medical "battles"

Around midnight, 28-year-old Dr. Nguyen Thi Quynh Huong and her team received a call about a traffic accident in Tan Phu District (formerly). The caller described the victim as having multiple injuries, bleeding, and being unresponsive. The team prepared splints, bandages, and other specialized equipment, arriving at the scene within 15 minutes.

Dr. Huong's first action at every traffic accident scene is to instruct someone to call the traffic police and local authorities. This is a "mandatory" step to ensure the safety of the emergency team before they can focus on treating the victim.

In her two years on the job, Dr. Huong has encountered numerous tense situations: arguments, conflicts, and even assaults against emergency personnel. She considers these unavoidable non-medical "battles."

|

A man in a car loudly obstructed the rescue, disrupting the work of the emergency team. Photo: Phung Tien

As the team arrived, tension filled the deserted street. The victim lay moaning on the pavement while a man shouted, cursed, and prevented the team from approaching.

"This guy can still smoke; why bother saving him?" the man yelled.

The stretcher was ready, but the team had to hold back. The authorities hadn't arrived yet. Amidst the chaos, Dr. Huong stepped back and called the ERC for backup: "Send the police immediately."

Just the week before, she had treated a patient who was a debtor and went into cardiac arrest on the spot after a heated argument. When they realized he couldn't be saved, his family turned their anger on the creditor, starting a brawl in the alley. The scene turned into a chaotic fight.

|

After the authorities arrived, the emergency team began first aid and administered an IV to the victim. Photo: Phung Tien

The WHO estimates that 8% to 38% of healthcare workers experience physical violence or verbal threats and abuse during their careers, mostly from patients and their families. Another study found that pre-hospital emergency personnel are almost three times more likely to experience physical and verbal violence than other healthcare workers.

Such incidents not only hinder treatment but also have a lasting psychological impact on emergency responders.

According to Dr. Nguyen Duy Long, each healthcare worker reacts differently to such conflicts. Some choose to cope silently, sharing their experiences with colleagues, while others resign due to the unbearable pressure.

In 2024, Ho Chi Minh City’s Department of Health reported that nearly 20% of healthcare workers showed signs of depression, 23% experienced anxiety, and over 14% faced stress. This is a global trend. A large-scale US survey in 2015 found that 46% of physicians experienced burnout, with the rate among emergency and critical care physicians reaching 52-53%, the highest among all specialties.

This stress, combined with irregular sleep patterns and inadequate diets, contributes to the increasing prevalence of job burnout in the emergency medical field. High-intensity stressors can lead to anxiety, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

According to Dr. Nguyen Duy Long, Director of the ERC, most pre-hospital personnel are young and passionate doctors. But their youth also means they enter the profession under harsh conditions: traumatic scenes, emotional turmoil, and sometimes even threats. In many cases, patients or their families are uncooperative, even turning to pressure and threats against the medical team. These factors present not only professional challenges but also tests of their mental fortitude.

"This kind of pressure isn't easily erased. It's silent, but it lingers," Dr. Long said.

Unlike the controlled environment of in-hospital emergency care, pre-hospital teams face various working conditions, including cramped, poorly lit spaces. Photo: Hoang Viet

To ensure the safety and mental well-being of its pre-hospital teams, the ERC has implemented several measures: increased training in field situation handling and close coordination with local police in potentially conflict-ridden cases.

According to Dr. Long, every morning meeting is an opportunity for the team to review the previous day's fatalities, emergencies, and unusual incidents. Everyone shares their experiences and learns from them. While words of encouragement may not immediately alleviate grief, they provide a sense of understanding and motivation to return to their familiar "battlefield."

Beyond systemic support, empathy from the community is equally crucial. Many healthcare workers share a lingering sense of "guilt" after an unsuccessful emergency response, even when the outcome isn't due to medical error.

|

A nursing intern sits quietly on the return trip to the ERC after an unsuccessful emergency call. Photo: Hoang Viet

At 5:30 a.m., while waiting to take his mother home, Duy received a call from a doctor at the ERC. Only then did he learn the name of the person who had tried to save his mother the previous night.

"My mother didn't make it…," Duy informed Dr. Tan.

After a brief silence, Dr. Tan offered his condolences, and both quietly ended the call.

"They did their best," Duy said, no longer blaming the team for causing his mother pain.

The conversation lasted less than two minutes, but it left Dr. Tan saddened for the rest of the day. He has maintained the habit of following up on critical cases for several years to check on the patients' conditions. He's gradually learning to accept giving his all, yet sometimes helplessly watching life slip away.

"I have to learn to accept it as part of the job. If I dwell on the sadness, I can't continue working in emergency medicine. There are critical cases every day. I have to know that I've done my best," he reminded himself.

|

Each time the bell rings at the ERC, doctors and nurses rush into the race to save lives. Photo: Khuong Nguyen

Content: Phung Tien - May Trinh - Le Phuong

Photo - Video: Hoang Viet - Khuong Nguyen

Part 1: Behind the emergency call Part 2: Emergency responders under pressure Part 3: ERC staff: 'We are not transporters' Part 4: The blurred line connecting emergency care |