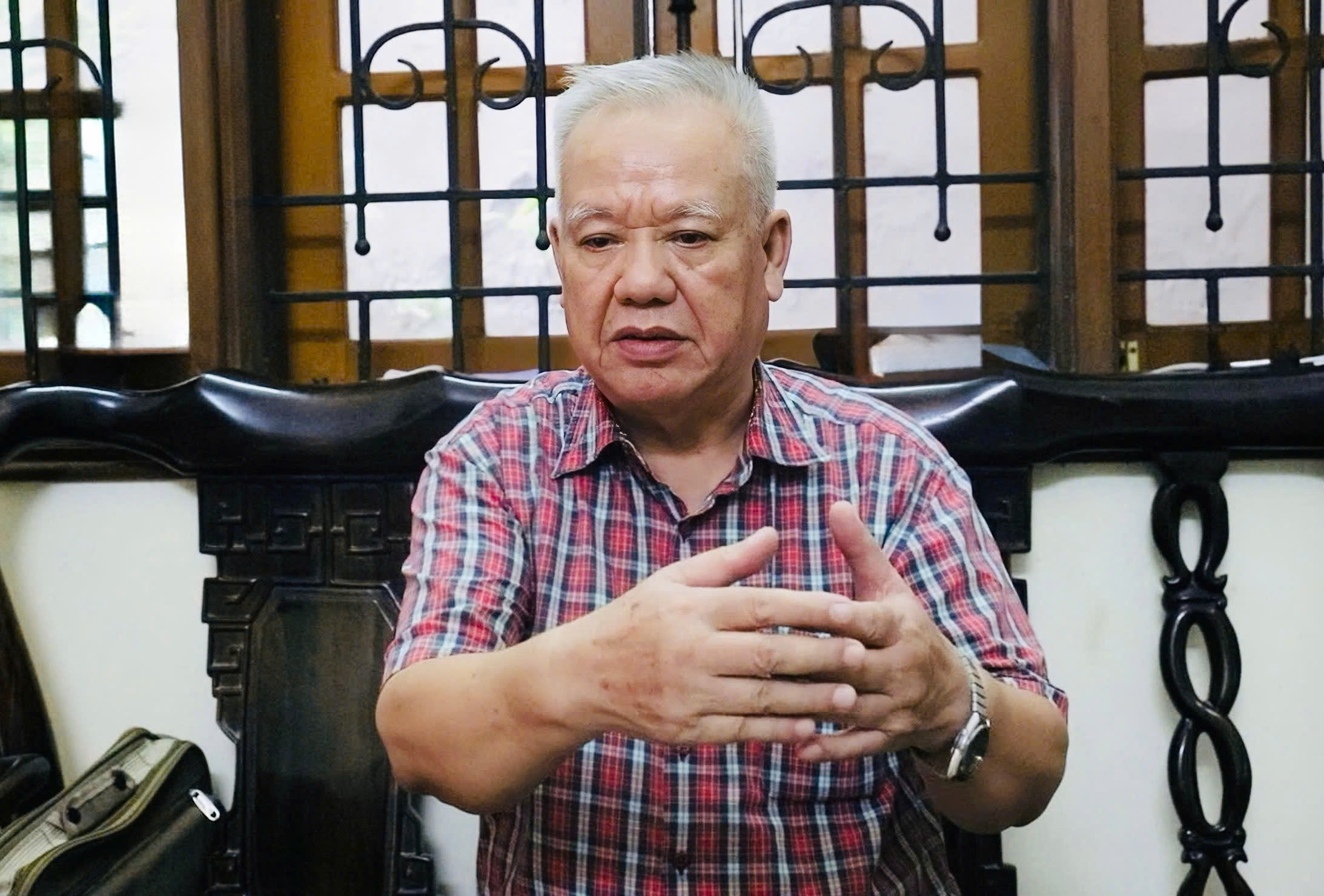

In late September, in a house on Tran Cung street, Cau Giay, 78-year-old Doan Nhu Lam and his fellow telegraph operators gathered to reminisce about their "battle" on the airwaves 57 years earlier.

"For seven years on the battlefield, we received and transmitted hundreds of thousands of telegrams to the north. But the most moving was the one announcing the victory on the morning of 30/4/1975," Mr. Lam recounted.

That day, at 8 a.m., Mr. Lam's station, located at the National Liberation Front's headquarters in Tay Ninh, received a plaintext (uncoded) telegram from a station accompanying Vo Van Kiet, the Secretary of the T4 Party Committee (Saigon-Gia Dinh area): "Reporting to the Standing Committee. We have received Duong Van Minh's surrender. We are preparing to enter. Signed: Sau Dan."

Telegraph operator Le Quy Dieu received the message. However, because the telegram was sent in plaintext, violating security protocol, Mr. Lam's station initially refused it. The sender insisted it was urgent and needed immediate relaying to the National Liberation Front, so the station complied.

The telegram was later confirmed as authentic, sent by Mr. Sau Dan (Vo Van Kiet's alias). The news of victory sparked jubilation. "People hugged each other and cried, some sang, and I fired my gun into the air in celebration. We knew that our country was finally unified," Mr. Lam said.

|

78-year-old Doan Nhu Lam recounts his journey across the Truong Son trail to support the southern battlefield. Photo: Nga Thanh |

78-year-old Doan Nhu Lam recounts his journey across the Truong Son trail to support the southern battlefield. Photo: Nga Thanh

In April 1968, 21-year-old Doan Nhu Lam, a Hanoi Post Office employee, embarked on the arduous journey across the Truong Son trail to serve as a telegraph operator in the south.

During the Vietnam War, communication was crucial. The north-south information network relied on three methods: telephone, mail, and radio. Radio was the fastest but most dangerous, as each transmission risked detection and attack.

The mission of telegraph operators from the north was to maintain uninterrupted communication, even under the harshest conditions. Thousands of young people like Mr. Lam volunteered for this duty.

Mr. Lam's group of 200 traveled by car from Hoa Binh to Ha Tinh, then trekked for five months through the Truong Son mountains. These postal workers, accustomed to machines and Morse code, now faced a test of survival, conquering steep slopes, battling malaria, and enduring enemy attacks. Many perished in the jungle.

"Our goal was to reach 'B2 S9 Ong Cu'," Mr. Lam explained, the codename for the B2 battlefield logistics, one of the fiercest battlegrounds in the south.

Former telegraph operators from the north recount their experiences during the Vietnam War, from 1968 to 1975. Source: Quynh Nga

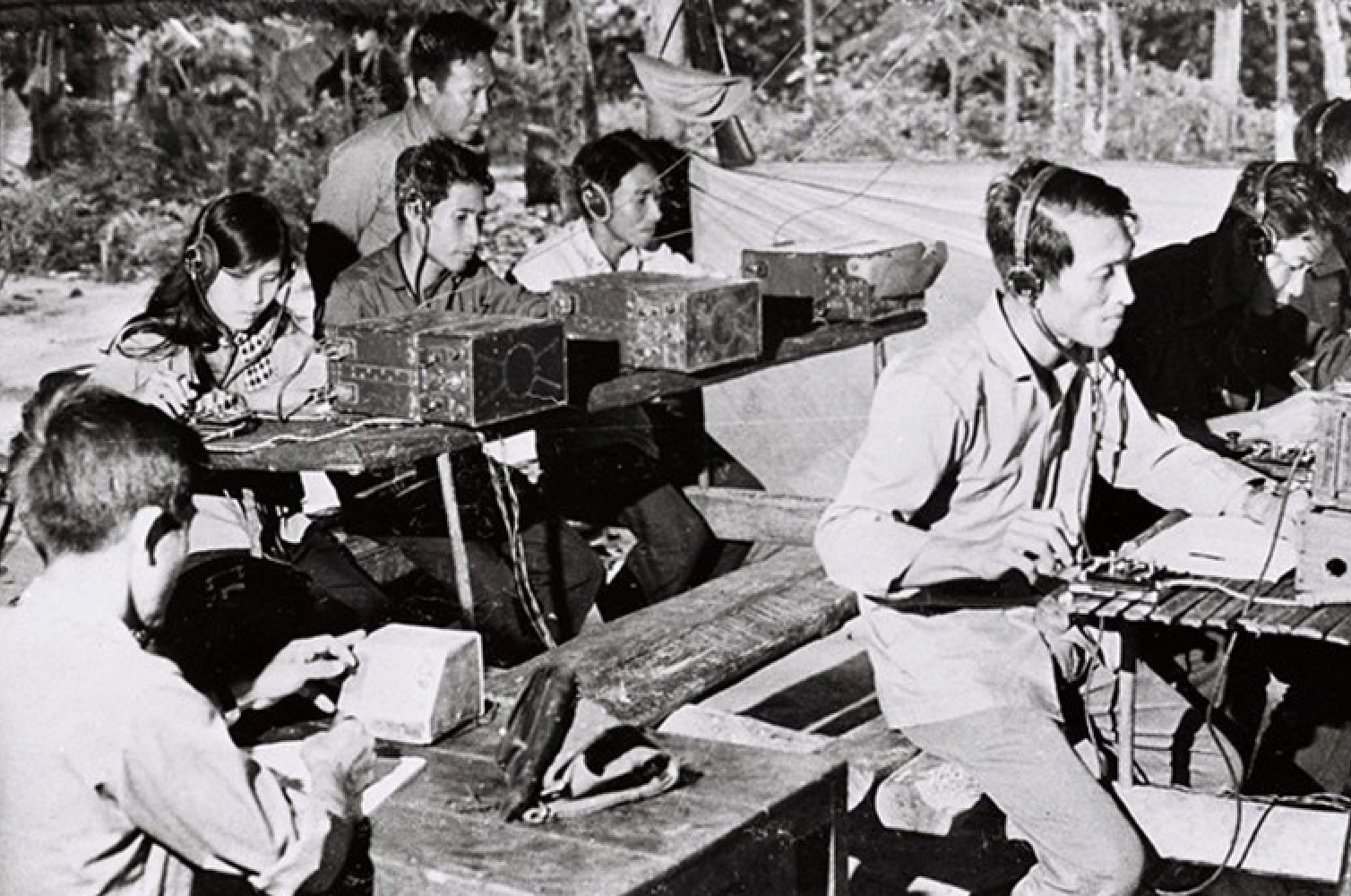

Upon arrival, Mr. Lam was assigned to station B20. Work primarily took place at night, when signals were prone to interference. Telegraph operators required intense focus, one hand tapping code, the other adjusting the receiver. Their ears strained to hear both their colleagues' Morse code and the sound of enemy aircraft. At the slightest rumble, transmissions ceased to avoid detection and bombing.

This was a constant mental battle. To survive, stations constantly relocated, changed frequencies, and adhered to strict rules: no cooking, no loud talking, and no returning fire when ambushed to maintain secrecy.

"The communications unit also set up a decoy station, B6, which transmitted jamming signals to attract enemy attention, drawing B-52 bombers towards it while the main stations operated safely," Mr. Lam shared.

|

A radio station of the R Radio Information Unit (Central Office of Communications) in the Tan Bien war zone before 1975. Photo: VNPT TP HCM |

A radio station of the R Radio Information Unit (Central Office of Communications) in the Tan Bien war zone before 1975. Photo: VNPT TP HCM

In March 1970, Mr. Lam's station relocated to Cambodia to evade enemy sweeps. Each person carried a part of the communication equipment, navigating the jungle while dodging B-52s. Three months later, the enemy located their new base. B-52s bombed relentlessly every 15 minutes. The unit took cover in bunkers during attacks, emerging to work during lulls, surviving on roasted rice and stream water for days.

"Despite the constant bombing, our unit suffered no casualties. However, the neighboring B19 station, with five telegraph operators, was buried alive in their bunker," Mr. Lam recalled.

Vu Ngoc Luong, 77, also has vivid memories of Cambodia. After graduating from telegraph school in Ha Nam, he volunteered for service in the south at 24, four years after Mr. Lam. When B-52s disrupted supply lines, Mr. Luong's station resorted to trapping rats for food.

In late 1972, near the signing of the Paris Peace Accords, telegram traffic surged. Operators worked 3-4 days straight without sleep. "One hand on the receiver, one tapping code, and a foot pedaling the generator. To fight off sleep, I'd slap myself to stay awake and ensure accurate transmission," Mr. Luong said.

In April 1973, Mr. Luong accompanied the Party Secretary to Military Region 8 (Mekong Delta) to transmit vital intelligence to the National Liberation Front. He carried a 15W radio, antenna, generator, and other equipment, totaling almost 40 kg, while weighing just over 50 kg himself. Despite the muddy terrain and constant enemy pursuit, no one could fall behind. Their mission was to reach their designated position and transmit accurately.

For telegraph operators, equipment was more valuable than life. If ambushed, the first priority was burying the equipment before escaping.

|

From left: Doan Nhu Lam, Vu Ngoc Luong, and Nguyen Van Thanh, former telegraph operators who served in the south during the Vietnam War from 1968 to 1975, at a private residence on Tran Cung Street, Cau Giay, on the morning of 15/9. Photo: Nga Thanh |

From left: Doan Nhu Lam, Vu Ngoc Luong, and Nguyen Van Thanh, former telegraph operators who served in the south during the Vietnam War from 1968 to 1975, at a private residence on Tran Cung Street, Cau Giay, on the morning of 15/9. Photo: Nga Thanh

Nguyen Van Thanh, 75, head of the northern chapter of the Southern Information Block War Veterans Club, said thousands of postal workers from the north supported the south during the war, significantly expanding the communication network. Telegram traffic increased from 3,000-4,000 in 1968 to 80,000 per month by late 1973. Notably, of the nearly 300 radio stations operating across the south, 250 were assembled by the soldiers themselves.

Maintaining this communication network came at a cost. Over 20 years, the postal service suffered over 4,400 casualties and more than 2,000 injuries.

Individuals like Mr. Lam, Mr. Luong, and Mr. Thanh received the Order of Victory and numerous commendations. However, their joy of victory remains bittersweet.

"We were fortunate to return, but we mourn our fallen comrades. Many remain missing, their remains undiscovered, and their families without closure," Mr. Thanh lamented.

Mr. Thanh's club was established to honor these sacrifices. They not only share memories but also search for missing comrades, visit and support families of martyrs, offering solace and healing in the aftermath of war.

Quynh Nguyen - Nga Thanh