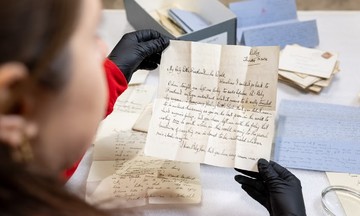

At a production workshop in Ha Ze, Shandong, Lisa Liu, 29, inspects intricate carvings on paulownia wood coffin lids. Her days, once filled with student chatter, now resonate with the sounds of saws and wood grinders.

Liu's daily routine now involves meticulously checking coffin quality, such as the lightness of a unit prepared for export to Italy. This shift occurred in 7/2023, when Liu, exhausted by years of teaching that left her hoarse and under immense pressure, decided to leave her profession. A chance interview then led her to this coffin factory in her hometown, where she now serves as the international trade manager, entering an industry often seen by many as a "bad omen."

In Trung Quoc, the topic of death is often associated with bad luck, a belief Liu initially shared. Her apprehension faded, however, when she observed factory workers casually using unused urns to hold personal belongings. To them, coffins and urns were merely wooden handicrafts.

"I realized that birth, aging, sickness, and death are natural laws," Liu stated, "and that a coffin is an essential need when someone passes away."

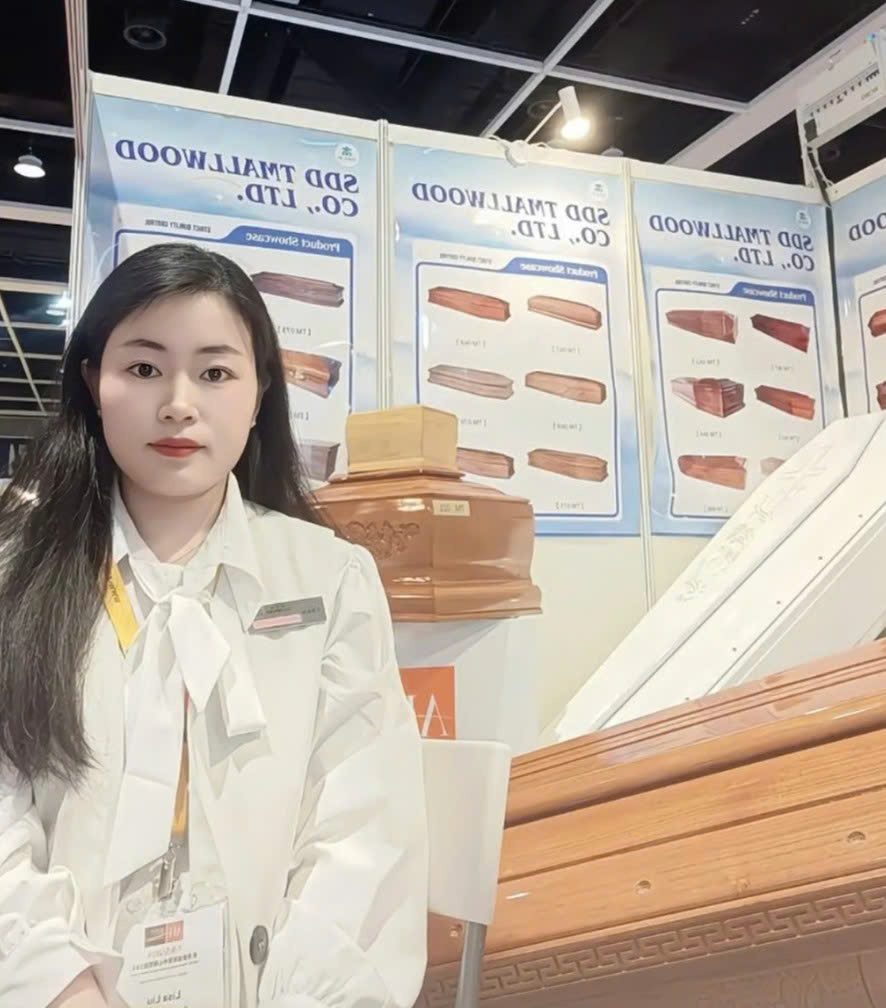

|

Lisa Liu, 29, in Ha Ze, Shandong, Trung Quoc. Photo: QQ |

Inspired by the workers' pragmatic approach, Liu began extensive market research. She identified significant cultural distinctions: traditional Trung Quoc coffins are typically heavy and dark, whereas European clients favor lighter designs adorned with intricate religious carvings. In some European nations, where bodies are cremated with the coffin, the material must be easily combustible while retaining its aesthetic appeal.

"Our factory exclusively uses paulownia wood sourced directly from Ha Ze," Liu explained. "This wood is light, possesses a beautiful grain, and perfectly meets Europe's strict standards." She noted that a raw coffin priced at 90-150 USD in Ha Ze can retail for up to 2,100 USD for European consumers.

"With people passing away daily, demand remains consistently stable," she observed. The factory currently exports approximately 40,000 units each year, generating nearly 40 million yuan (around 6 million USD) in revenue.

Ha Ze is not alone in profiting from the funeral services sector in Trung Quoc. Mibeizhuang village in Hebei province stands as the nation's largest funeral supplies hub, with its production value surpassing one billion yuan in 2020. Similarly, Huian, Fujian, earns nearly two billion yuan annually from exporting stone gravestones to Nhat Ban.

Furthermore, domestic businesses are adept at exporting biodegradable joss paper to Western markets. In the US, a stack of "hell money" (spirit money) imported from Trung Quoc for two USD can fetch 15 USD at retail.

This multi-billion dollar industry's robust growth is partly fueled by a more open perspective on death among younger generations in Trung Quoc. They are increasingly challenging traditional taboos. Recent trends include young people designing personalized, even spaceship-shaped, coffins for themselves. In Thuong Hai, "death cafes" have emerged, inviting patrons to share stories about life and death in exchange for complimentary beverages.

Luo Yan, an associate professor of sociology at Hoa Trung University of Science and Technology, describes this phenomenon as the "normalization" of attitudes towards death. A growing number of young individuals are entering the funeral industry, taking on roles such as cemetery designers and service managers.

"Facing death directly helps young people shed superficial pressures and learn to appreciate their present lives," Luo stated. She advocates for educational discussions on life to be held in public venues like libraries and museums.

Thanh Thanh (NDTV, Hindustan Times, SCMP)