"To create these 11 km of tunnels, my entire village had to dig for three months using knives and shovels," said Nguyen Thi Lai, 87, from Phuc Thinh commune (formerly Nam Hong commune), Dong Anh district.

She is not only a historical witness but also one of the people who, for almost 80 years, has taken on the responsibility of preserving and protecting the tunnel system. Her modest 30-square-meter house is also one of the two remaining tunnel entrances today. The other entrance is located within the premises of Pham Van Doc's house, in the same commune.

|

Nguyen Thi Lai, 87, next to the tunnel entrance located under her bed in Ve hamlet, Phuc Thinh commune (formerly Nam Hong commune), Hanoi, on the morning of 13/8. Photo: Nga Thanh |

Nguyen Thi Lai, 87, next to the tunnel entrance located under her bed in Ve hamlet, Phuc Thinh commune (formerly Nam Hong commune), Hanoi, on the morning of 13/8. Photo: Nga Thanh

At the end of 1946, Dong Anh district was chosen as a safe zone for the central government's headquarters in the face of intense French raids. Nam Hong commune, where many high-ranking officials operated, became a primary target. In 1/1947, the Nam Hong guerrilla team was formed with the determination to "hold the land, keep the village". The idea of digging an interconnected tunnel system for long-term resistance was embraced by both the government and the people.

"The young men had gone to war, so those digging the tunnels were all women over 40. We divided into groups: some dug, some shoveled, some carried the earth. Each group had to dig 10 meters of tunnel per day," Lai recounted.

Their tools were short-handled hoes about 40 cm long and hammers. The work took place in absolute secrecy. The excavated earth was placed in sedge mats and scarves, then carried to the river or mixed with garden soil to avoid detection by the enemy.

After three months, nearly 11 km of tunnels running through the hamlets of Tang My, Doai, Dia, and Ve of Nam Hong commune were completed, connecting to Bac Hong and Nguyen Khe communes. The tunnels had a fishbone structure, with a main shaft connecting branches leading to each household, along with 465 secret bunkers and over 2,600 fighting pits.

One of the two remaining entrances is located directly beneath Lai's bed in her main room. The entrance was camouflaged with a piece of wood, covered with bamboo, and then filled with earth level with the floor. The entrance is just wide enough for two shoulders, but it widens further inside, reaching a height of about 60 cm, facilitating movement.

|

Duong Van Giang, 97, redraws the Tam Hung tunnel system at his home in Van Khe hamlet, Tam Hung commune, Hanoi, on the afternoon of 13/8. Photo: Quynh Nguyen |

A tunnel entrance located under the bed in the modest house of Nguyen Thi Lai, 87, in Phuc Thinh commune (formerly Nam Hong commune).

|

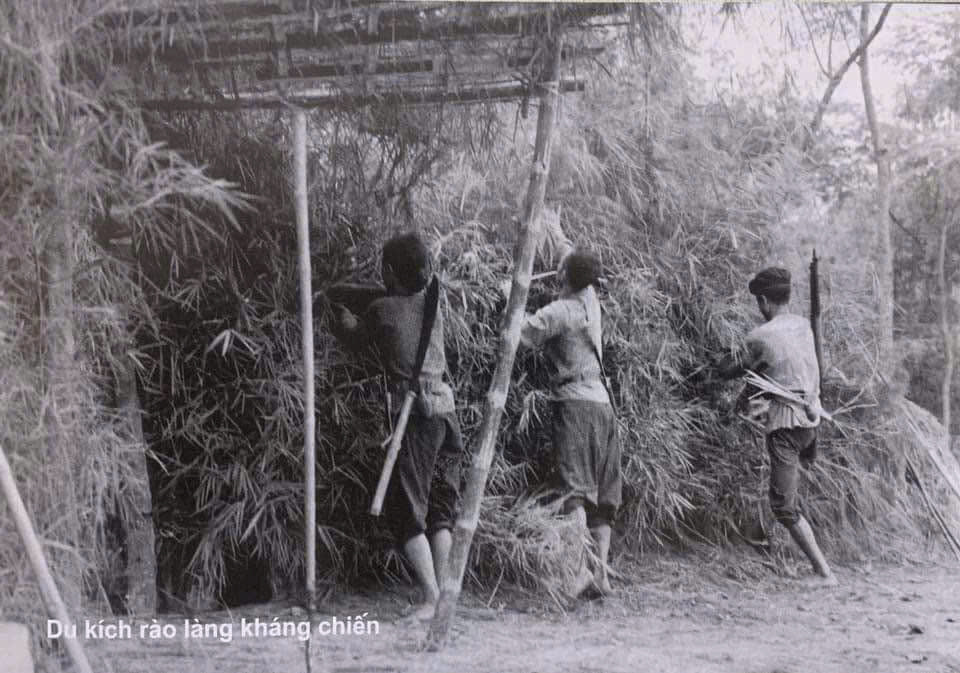

Tam Hung guerrillas utilized the bamboo hedges surrounding the village to create an impenetrable barrier. Photo: Historical archives of Tam Hung commune |

Compared to the original tunnel entrance, the current one is wider to accommodate visitors.

|

Apart from the restored entrance, the entire tunnel system remains in its original state.

|

The tunnel has a unique fishbone structure, with a main shaft connecting branches leading to each household.

|

A total of 11 km of tunnels were dug by the people of Nam Hong commune through the hamlets of Tang My, Doai, Dia, and Ve, connecting to Bac Hong and Nguyen Khe communes, over three months.

|

Nguyen Thi Lai's grandson, descending into the tunnel from the family's entrance.

|

Some damaged and collapsed areas within the tunnel have been repaired by the local authorities.

When the tunnels were completed, protecting the officials became the top priority. Whenever there was an alert, people evacuated to bomb shelters in the fields. "No civilians went down into the tunnels, as they were reserved for soldiers and to avoid being discovered," Lai explained.

The sacrifices made by the people of Nam Hong to protect the secrecy of the tunnel system are immeasurable. The enemy suspected but could not find them. They continuously terrorized, tortured, and even beheaded a villager as a warning. Two guerrillas were captured upon exiting the tunnel, and despite brutal torture, they refused to reveal anything and were eventually hanged in Lai's garden.

"Who could bear to see their loved ones killed, but for the revolution, everyone had to endure it," she said.

From 1947 to 1950, French looting and bombing left the fields abandoned, and people suffered constant hunger but still shared their food with the officials. Cooked rice was hung in bamboo clusters near the tunnel entrances for the soldiers to retrieve at night.

Guerrillas and residents of Nam Hong commune fought 308 battles but also endured 244 raids and the destruction of over 2,000 houses.

In 1/1996, Nam Hong commune was awarded the title of "Hero of the People's Armed Forces". The Nam Hong tunnel system was recognized as a National Historical-Cultural Relic, with about 200 m preserved, serving as a testament to a heroic historical period.

|

Duong Van Giang, 97, redraws the Tam Hung tunnel system at his home in Van Khe hamlet, Tam Hung commune, Hanoi, on the afternoon of 13/8. Photo: Quynh Nguyen

Nearly 40 km from Nam Hong, the resistance village of Tam Hung also built an "underground fortress". Initially, the tunnels were used to shelter officials and store food, later becoming a fighting position to block enemy raids.

Duong Van Giang, 97, one of the key guerrillas of that time, explained the village's importance: "Holding Tam Hung meant securing a safe corridor for the Ha Dong province's base. Losing Tam Hung would allow the enemy to threaten a vast area, so we were determined to hold it at all costs."

From 1948, the people of Tam Hung implemented the policy of "each village a fortress". Before digging the tunnels, the whole village built a ground defense system. Dense thickets of thorny bamboo surrounding the village were woven together to form natural walls. The only paths into the village were blocked, replaced by a network of communication trenches, camouflaged gun emplacements, and punji stake pits.

The entire village became a fighting unit, each person with a task such as guarding, preparing food, sharpening stakes, or digging tunnels. A widespread defense was set up, ready for the enemy.

Unlike Nam Hong, Tam Hung's soil is a mixture of clay and gravel, hard and difficult to dig. The tools were still rudimentary, including only short-handled hoes, hammers, and shovels. The soldiers and civilians divided into 6 groups, tasked with digging tunnels connecting the hamlets. The tunnels were about 1.2 m underground, 1.5-2 m high. "We just squatted and dug, switching shifts when tired. The more we dug, the more enthusiastic we became, just hoping to finish quickly so the soldiers would have a place to hide," Giang recalled.

To maintain secrecy, the excavated earth was put into baskets and winnowing trays, waiting until nightfall to be transported to the fields. "We didn't dump the earth into the ponds because it would be easily detected. The earth was carried to distant fields and spread in thin layers so no one would notice," Giang said.

|

Tam Hung guerrillas utilized the bamboo hedges surrounding the village to create an impenetrable barrier. Photo: Historical archives of Tam Hung commune

The Tam Hung tunnels were not dug straight but winding and zigzagging to limit the damage from grenades and the enemy's firing angles if they entered. Every few meters, there was a sudden turn or a "bottleneck" - a section of the tunnel suddenly narrowed, just enough for a thin person to squeeze through. This design aimed to stop large French soldiers, giving the guerrillas time to retreat safely. Ventilation holes were cleverly disguised as termite mounds, mounds of earth, or kitchen vents in houses, with smoke blending into the air, making it impossible for the enemy to suspect.

In over a year, the people of Tam Hung created a defense system consisting of nearly 8 km of bamboo fences, over 400 secret bunkers, and nearly 5 km of tunnels.

This system transformed Tam Hung into an impenetrable fortress, the "backbone of the guerrilla warfare strategy", where suicide squads could appear and disappear like ghosts to attack enemy posts and then vanish without a trace.

Giang recounted times when French troops occupied the village for 2-3 days, walking on the ground unaware that civilians and guerrillas were living right beneath their feet. The highlight was the raid on 19/9/1949. Tam Hung guerrillas repelled multiple attacks by nearly 1,000 French troops supported by artillery. This victory led the Ha Dong Provincial Committee to promote the "Tam Hung Resistance Village" model throughout the province.

To maintain absolute secrecy for the base, many people accepted sacrifices. Until the liberation of North Vietnam, the Tam Hung tunnel system was never discovered.

In 12/1949, the Lien Viet Front awarded the commune four golden words: "Tam Hung Anh Dung" (Tam Hung Heroic). In 12/1995, the commune was awarded the title of "Hero of the People's Armed Forces" by the State.

At the age of 97, Duong Van Giang, one of the creators of the legendary tunnel system, concluded: "Being Vietnamese means not being afraid of hardship. The strength of the people is the key factor that creates historical victories."

|

The only remaining entrance to the Tam Hung tunnel system, located within the Boi Khe pagoda area, Tam Hung commune.

|

To accommodate visitors, 18 m of the tunnel have been renovated and widened compared to the original design.

|

The tunnel displays photographs and artifacts used by the people of Tam Hung during the resistance against the French from 1948.

|

The tunnel displays photographs and artifacts used by the people of Tam Hung during the resistance against the French from 1948.

|

In addition to war memorabilia, the tunnel displays flags recognizing the commune's contributions to the resistance, including the four golden words "Tam Hung Anh Dung" awarded by the Lien Viet Front in 12/1949. In 12/1995, the commune was awarded the title "Hero of the People's Armed Forces" by the State.

|

Archival photo of the Tam Hung Guerrilla Team.

|

Members of the Tam Hung Guerrilla Team practicing martial arts in front of the Boi Khe Pagoda gate in the late 1940s.

|

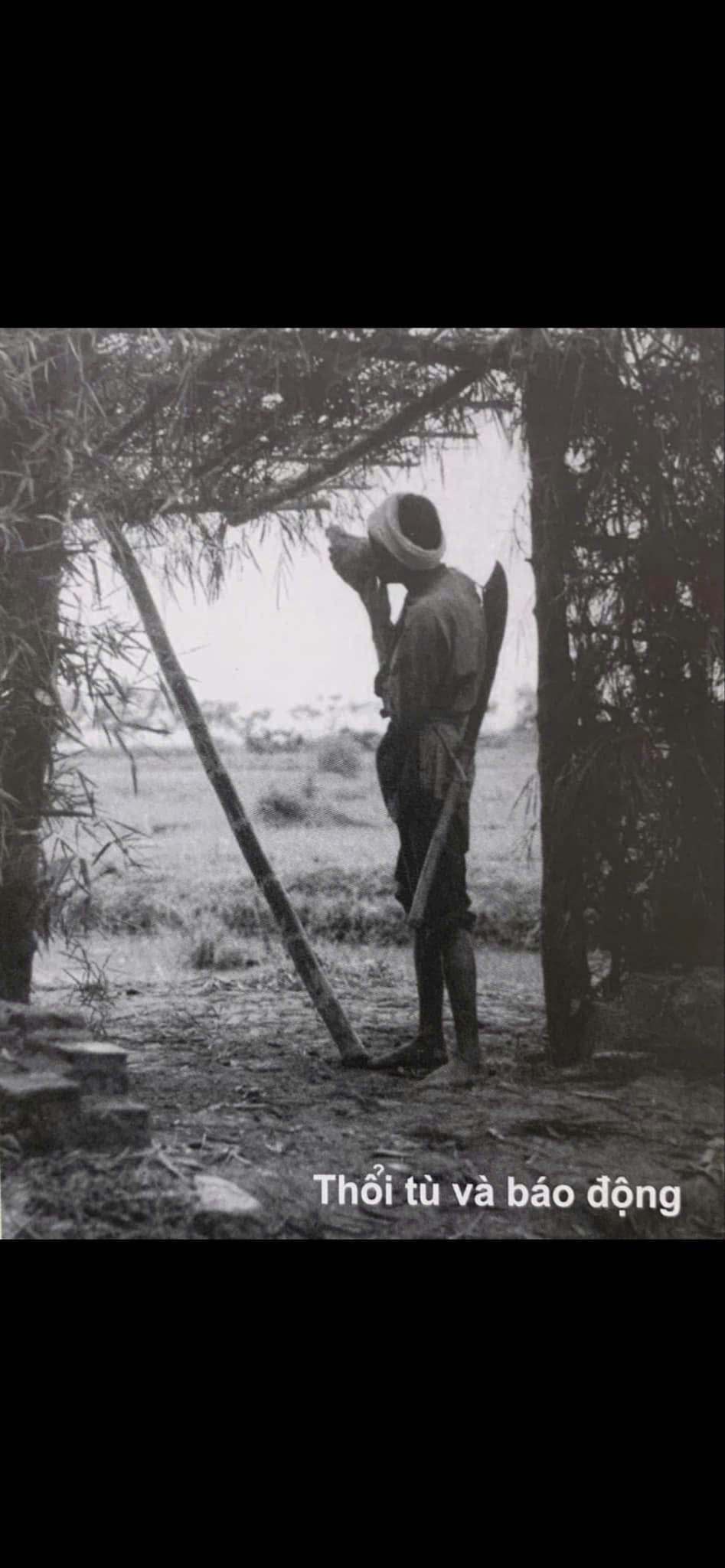

Militia members of Tam Hung commune blowing horns to warn of an impending French attack.

|

In 12/1995, the commune was awarded the title "Hero of the People's Armed Forces" by the State.

Quynh Nguyen - Nga Thanh