In an English classroom, South Korean preschoolers fidget restlessly. They are not learning the alphabet but are getting an early start on a decisive milestone over 10 years away: the university entrance exam.

"Write a paragraph of 5-8 sentences, using five synonyms for the word 'big'," teacher Keri instructs. The children begin their assignment.

The students in Keri Schnabel's class, taught by the 31-year-old American, are among a growing number of South Korean children who begin private education programs early. These programs almost always focus on improving English proficiency, a crucial language for future career paths.

|

Keri Schnabel's English class in Seoul, South Korea in June 2025. Photo: WP |

For years, Lee Kyong-min's life revolved around shuttling her two daughters from school to private academies and then home. Lee, a former advertising professional, and her husband, who works in finance, strived to enroll their children in the best possible institutions.

Seven days a week, she waited for her children until late at night in cafes packed with other parents. Sometimes, she saw young children doing homework while eating dinner right in the cafe before rushing off to their next class.

Private academies are now ubiquitous across South Korea, meeting the demands of many parents who want their children to gain admission to the top universities.

When her daughter asked why she had to spend so much time at hagwons, Lee told her children it was necessary because academic achievement meant opportunities, and opportunities would lead to a happy life. However, her belief in this idea began to waver when her elder daughter, then around 8 years old, asked, "Mom, were you bad at studying when you were young?"

"I realized she saw that I wasn't happy. I felt like I had been hit hard on the head", Lee said.

Now, this mother questions what kind of life and happiness she is envisioning for her children. This is a question many South Korean parents face.

According to government data, 80% of South Korean students participate in private tutoring. Despite a decline in the school-age population over recent decades, this market still grew to a record 20,3 billion USD in 2024.

South Korean children are starting private courses and test preparation earlier and earlier. In one Seoul district, children as young as 4 years old take entrance exams for English-language kindergartens. Some children begin preparing for medical school entrance from elementary school.

Even in a country accustomed to fierce university competition like South Korea, this situation is concerning. The National Human Rights Commission of Korea stated that subjecting preschoolers to such high-stakes exams violates children's rights. Lawmakers, who blame test-prep centers for the mental health crisis among teenagers, affirm they will intervene.

However, Lee does not believe this reality will change easily. She herself is conflicted about putting her children into the educational grind. Part of her wants her children to have a rich education and not be dependent on university competition. But another part wants them to be among the winners.

In 2013, she enrolled her daughters, then just 4-5 years old, in an English-language kindergarten. She also mentioned they attended numerous private academies in Daechi, an affluent neighborhood in Seoul's Gangnam district. This area is home to approximately 1.200 such test-prep centers.

Lee grew up in Daechi and was familiar with its reputation. Still, she was shocked by the endless cycle of exams awaiting her children.

|

A street in Daechi district, Seoul in December 2025. Photo: Yonhap |

Most important are the "level tests" or entrance exams organized by private academies (also known as hagwons) for children from 4 years old. Some tests are so competitive that parents must send their children to another hagwon for preparation just to take the entrance exam for the desired one.

"People often say that if you want your child to get into medical school, you need to have them 'grind' through the entire high school math curriculum six times", Lee said.

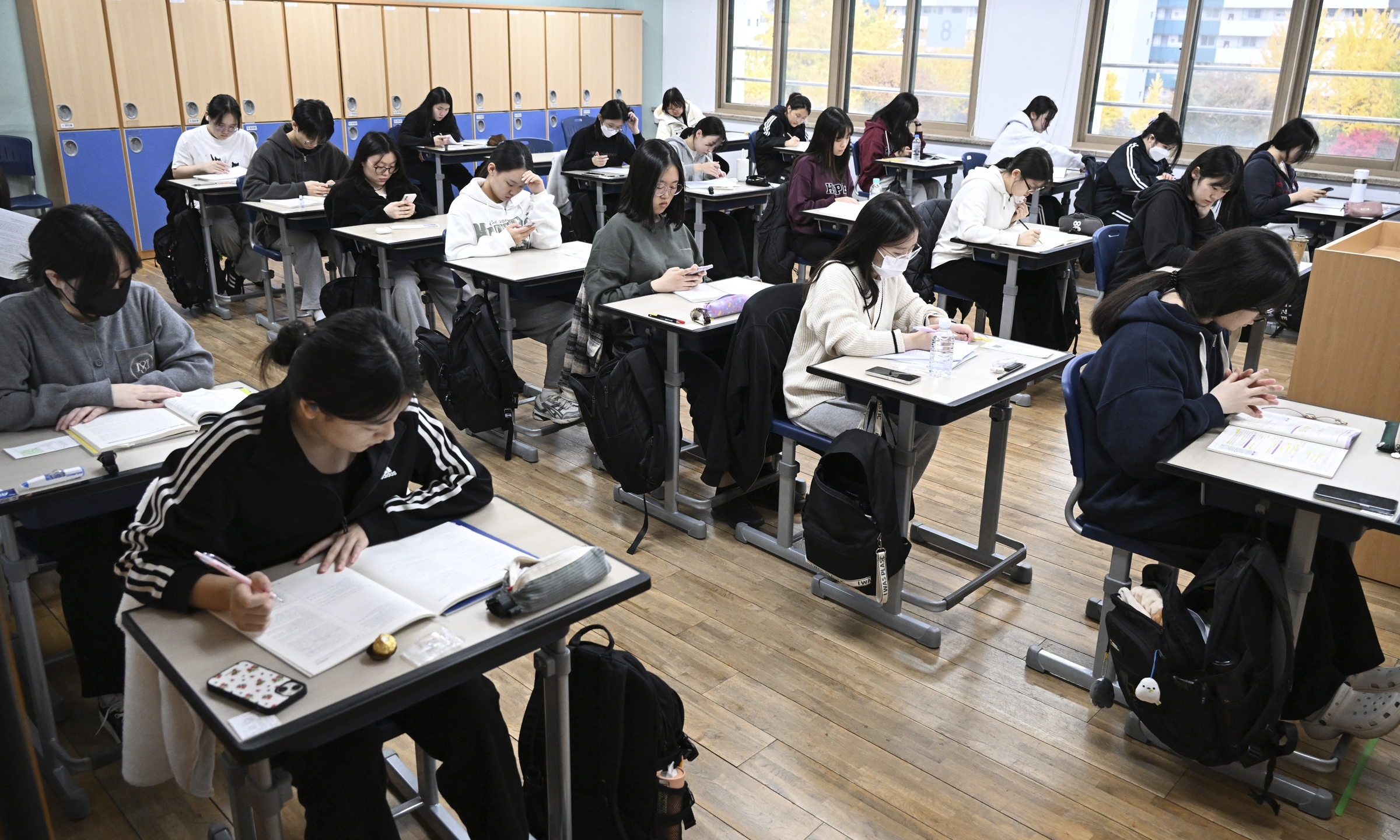

Anxiety still surrounds the Suneung university entrance exam, a "life-or-death" test whose scope and difficulty far exceed the standard school curriculum.

"Students today essentially bear two separate workloads: school grades and preparation for the Suneung exam", said Gu Bon-chang, a former teacher and current policy director for the non-profit World Without Worries about Shadow Education.

South Korea has one of the highest university enrollment rates in the world at 76%.

"There are no second chances in South Korea", observed Soo-yong Byun, a professor at Pennsylvania State University. "It's not just where you attend university, but also the first job you get afterward. All these factors have a huge impact on your ability to advance as an adult".

A teacher at a leading English test-prep chain estimated that his elementary school students spend at least 40 hours a week just on private lessons. He said he was shocked when grading a recent essay by a student, in which the 6-year-old wrote about her fear that her entire family would not be happy if she did not achieve academic excellence.

Kim Hye-jin, 37, also enrolled her child in private English classes in the Daechi area from a young age. "They say children today don't meet friends on the playground anymore but at the hagwon", Kim said. "That's unavoidable. As parents, I can only try to make the best decisions possible".

Kim and many other parents worry their children will burn out. But they also fear their children will fall behind their peers or be excluded from a system that promises elite education and a successful life.

|

Candidates prepare for the university entrance exam at a test site in Seoul, South Korea on 14/11/2024. Photo: AFP |

Peter Na, a psychiatrist at Yale University, expressed concern about the rise in depression symptoms among South Korean children under 10 years old. "Depression at ages under 10 is not common. I think it's related to academic pressures", he said.

Seo Dong-ju, a 41-year-old doctor in Seoul, does not believe the fiercely competitive test-prep path is the right choice for his son. Seo is concerned about the long-term physical, psychological, and social impacts of excessive studying on young children.

"I think this culture needs to change fundamentally", he said.

Lee, now a psychology expert, has also chosen a different path for her children. In 2024, she and her husband decided to remove their children from South Korea's intensely competitive private academies and enroll them in a private boarding school in the US. Now, her daughters are thriving at their new school.

"Just study math in Daechi to an 8th-grade level, then go to the US. Everyone will call you a genius", she said.

Thanh Tam (According to NYTimes, Washington Post, Korea Herald)