From small workshop to Parisian shelves: the rise of Vietnamese chocolate.

On the last night of 2018, as fireworks lit up the sky, Nguyen Hong Huy sat in the reception of a small hotel in Bui Vien, TP HCM. Instead of celebrating, he wrestled with the financial calculations for his dream: building a chocolate production line using local cacao beans. After countless revisions, he finally decided to take the leap and invest everything he had.

Just over a year later, the first Hallelu chocolate bars emerged from his small Thu Duc workshop, produced on a machine he designed himself. The initial batch was shipped to France. "I vividly remember standing amidst the whirring machinery, hearing the news from my partner and thinking I was dreaming," Huy recalled. "I had to step outside and sit down to truly grasp that it was real."

The genesis of an idea

The idea sparked in 2017 during a trip to the Mekong Delta. Huy stumbled upon abandoned cacao orchards laden with neglected fruit. The price of fresh cacao had plummeted to a mere few tens of thousands of VND per kilogram. Traders stopped buying, and farmers resorted to chopping down their trees in despair. "At one point, cacao was only 30,000-45,000 VND per kg," he said. "Many lifelong cacao farmers had never tasted chocolate made from their own beans."

Nguyen Hong Huy inspects the drying process of cacao beans after harvest.

Intrigued, Huy delved deeper, uncovering the weaknesses of the domestic cacao industry. At the time, Vietnam had just over 3,400 hectares of cacao plantations – a modest figure compared to major exporters in West Africa and South America. Processing technology relied heavily on imported or manually assembled equipment, resulting in high costs and difficulties meeting export standards.

The question of why the Trinitario cacao variety – highly regarded by international experts – was being neglected haunted Huy. He embarked on a journey to learn the art of fermenting, roasting, butter pressing, and grinding cacao, determined to create high-quality chocolate right at the source.

His research revealed a promising niche: artisan chocolate. Unlike mass-produced chocolate, often made with blended beans and standardized recipes, artisan chocolate is crafted at the origin, preserving the unique flavors of the terroir. This became the guiding principle for Hallelu Chocolate.

6 months for a grinding machine

By day, Huy managed a small hotel in Bui Vien, a steady income that fueled his passion. By night, he'd travel nearly 40 km to Di An (Binh Duong, now part of TP HCM) to borrow a friend's warehouse and assemble his machinery. These evenings stretched late into the night, even through torrential rain, as he meticulously worked on each technical detail.

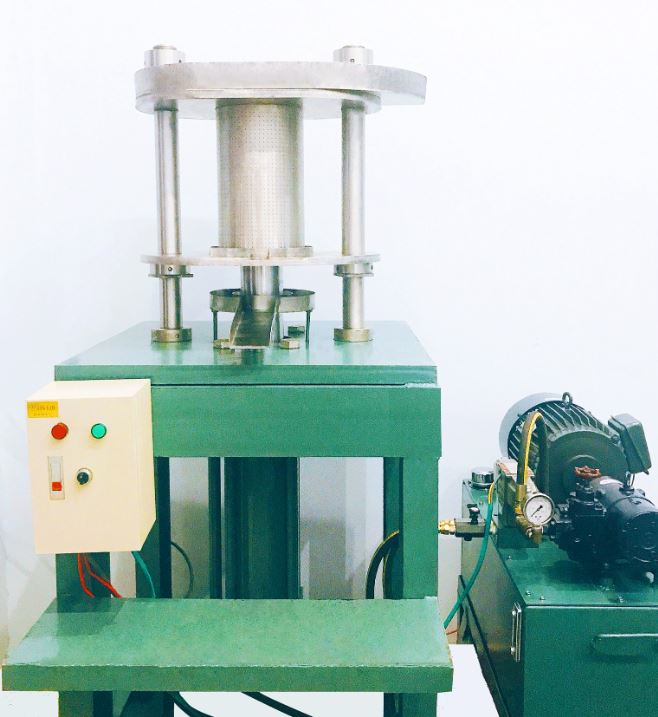

The first grinding machine took six months to complete, requiring over 100 dismantlings and reassemblies. The most challenging part was the grinding rollers, crucial for the chocolate's texture and taste. "Metal couldn't be used because it generates heat, which ruins the flavor," Huy explained. "I scoured quarries in Binh Dinh and Vung Tau to find the right natural granite, durable enough and able to maintain a stable temperature."

He once transported a hundred-kilogram granite block back to the city, spending a week cutting and polishing it to precise specifications. After numerous failed attempts, the machine finally ran smoothly. Huy poured roasted cacao beans into the hopper and pressed start. The machine hummed quietly, no longer the rattling sound of before. The beans transformed into a thick, glossy brown paste, flowing steadily.

"It felt like a dream come true," he recalled. For the next three days, Huy barely slept. He kept turning the machine on, watching the chocolate flow, then turning it off, then on again. "Like a child with their first toy," he said, his eyes shining as he remembered one of his most cherished moments.

|

A pressing machine in the Hallelu production line. Photo: NVCC

A homemade production line: going against the grain

Hallelu developed its own production line with six machines: a huller, butter press, grinder, tempering machine, vibrating mold, and enrober. The tempering and enrobing machines incorporated independent cooling systems – a first in Vietnam – ensuring a smooth, glossy finish suitable for the tropical climate.

"Chocolate needs to be cooled at a very precise temperature. A few degrees off, and it cracks or loses its shine," Huy explained. "I once stayed awake for 48 hours just to adjust the parameters. My eyes were swollen, my hands shaking from too much coffee, but seeing that first perfectly glossy chocolate bar, I knew I had succeeded."

Furthermore, IoT sensors are embedded in the fermentation tanks, continuously monitoring temperature and humidity for 5-7 days. "Hallelu only purchases beans with a fermentation rate of 95-100%. No added flavors. We preserve the original cacao taste of each region," Huy affirmed.

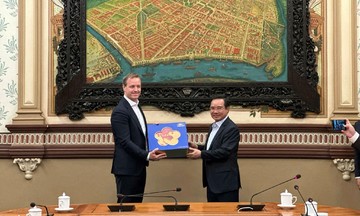

CEO Nguyen Hong Huy adjusts the cacao press and welcomes guests to observe the process.

Huy believes Europe's advantage lies in its technological mastery, while Vietnam possesses valuable raw materials. According to the Vietnamese chocolate entrepreneur, importing machines from the US, Germany, or China could cost up to 500 million VND for a small production line, while technical expertise would still be reliant on external sources.

Justin Jacquat, Asia-Pacific Cacao Manager, notes that the unique flavor profile of Vietnamese cacao has helped it capture the high-end market segment. However, to fully exploit this strength, the industry needs investment in further processing, technology application, and developing a sustainable supply chain from farms to businesses.

|

Hallelu products displayed at an airport shop.

Turning crisis into opportunity

In early 2020, the Covid-19 pandemic brought Hallelu's export activities to a standstill. Orders were canceled, markets froze, and revenue plummeted to zero. The company was forced to downsize from 30 employees to a core team of 8 to stay afloat.

"I knew that waiting passively would be fatal. We had to do something, anything, to survive," Huy recalled. He reassessed available resources, particularly cacao butter, the main ingredient in chocolate production. After much experimentation, a new product emerged: natural lip balm made from cacao butter.

"It started as a stopgap measure, but it unexpectedly gained traction in the market. This allowed us to maintain cash flow, retain staff, and avoid collapse during the most challenging period," he shared.

As the pandemic subsided, Hallelu reconnected with former partners and expanded its e-commerce channels for domestic distribution. The first orders trickled back, not in droves, but enough to restart the engine that had been idle for months.

Emerging from the crisis, Huy maintained his focus on artisan chocolate made with local ingredients. The production facility expanded, and the workforce gradually grew. Products like dried mango and chocolate-covered cashews were added to the export portfolio.

"I'm not chasing scale. The priority is quality control, preserving the flavor, so that every chocolate bar we produce is truly something to be proud of," Huy stated. This, he believes, is how Vietnamese cacao will earn its rightful place on the world map.

Profit beyond numbers

At Hallelu's small experience store in Thao Dien, dozens of customers, mostly foreigners living in the area, visit daily. During a conversation, Thomas, a French teacher, was surprised to learn that the chocolate was made entirely from Vietnamese ingredients. "The flavor is very natural and similar to what I used to have back home," he remarked.

Customers sample Hallelu chocolate at the experience store.

Not far away, at the 500 m2 workshop in Thu Duc, Huy walked among stacks of dried cacao beans nearly two meters high, calculating production plans in his head. A total of 7.5 tons of raw materials were ready for roasting, grinding, and processing. For him, this figure represented more than just output; it symbolized the connection between farmers and consumers. "If each year we can help a few dozen farming households improve their lives through cacao, then the company is on the right track," he said.

According to the International Cocoa Organization (ICCO), only about 12% of global cacao exports are classified as "fine flavor" – a premium category with distinct flavors and prices 5-10% higher than standard varieties. Vietnam was once recognized for having up to 40% of its cacao in this category, but most of it is still exported raw.

|

From a borrowed warehouse to a vertically integrated production system, Huy's entrepreneurial journey is not just a business story; it's a testament to restoring the value of Vietnamese cacao. The owner of Hallelu believes that farmers should take pride in their product, and Vietnamese consumers can enjoy quality chocolate that rivals imported brands.

Thai Anh