Latest data released last year by China's National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) confirms the country's demographic crisis is accelerating, with the population declining for the third consecutive year. By the end of 2023, China's total population decreased by 2.08 million people to 1.409 billion, a much sharper decline than the 850,000 people recorded in 2022. The number of newborns continued its downward trend to a record low of 9.02 million, a 5,6% drop from the previous year, while deaths increased to 11.1 million.

|

Shen Yang's family of four. Photo: HK01

When China officially abolished its one-child policy and allowed a second child in 2016, policymakers anticipated a population boom. However, reality painted a contrasting picture. The China Statistical Yearbook shows that the number of second births plummeted from a peak of 7.18 million in 2016 to just 3.72 million in 2022.

To understand this phenomenon, Professor Shen Yang from Shanghai Jiao Tong University and Professor Jiang Lai from Shanghai University of International Business and Economics conducted an extensive qualitative study since 2017. Their research involved more than 40 families in major economic centers such as Shanghai, Guangdong, and Jiangxi. The findings, published in 10/2024 in a report titled "The New Childbearing Era", reveal a demographic shift. Specifically, the group choosing to have a second child now primarily consists of the elite, those with high education and stable positions in the public sector. Their decision to have children no longer stems from the traditional belief of "more children, more blessings" but is the result of a rational calculation, where all risks and supporting resources are carefully weighed.

The primary motivation for these women to have a second pregnancy often arises from purely emotional needs: the desire for their first child to have a companion and the anxiety of losing their only child. However, between desire and reality lies a gap filled with demanding conditions. First is the "safety net" provided by family. In cities like Shanghai, where maternity leave is only 158 days but children must wait until they are three years old to be admitted to public kindergartens, the role of maternal grandparents becomes critical. This dependence is so significant that one interviewee admitted she had to "consult her mother before discussing it with her husband", and only after receiving her mother's approval was the plan to have a child activated.

But support from the older generation is only one half of the equation; the other half lies in the strict assessment of the husband. Before deciding to become pregnant, modern women must observe whether their partners are self-sufficient and willing to share household chores. Yet, even when husbands participate in child-rearing, women remain trapped in more subtle forms of inequality. As Shen Yang noted, the modern family has become "the most frequent and discreet arena for power struggles", where women bear the majority of "cognitive labor".

|

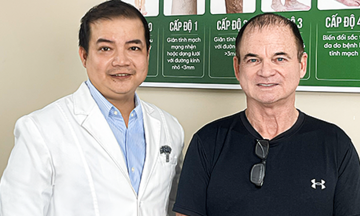

Professor Shen Yang feeding her second daughter. Photo: HK01

Cognitive labor is the invisible burden of planning, managing information, and making decisions—from choosing diapers to enrolling in school. He Yue's case exemplifies the loneliness of motherhood when her husband frequently traveled for work, leaving all major and minor decisions to her. Even for buying a house near a good school, from gathering information to real estate transactions, her husband was entirely absent.

Inequality also permeates aspects that seem open-minded, such as the right to name a child. Research indicates that about 20% of children carry their mother's surname, but this "privilege" often comes with expensive financial compromises from the maternal family. Song Yuhan's story reveals a reality where, despite living in a house bought by her parents, her husband secured a job through her father-in-law's referral, and she provided 3,000 yuan monthly to her in-laws, the husband's family still expressed dissatisfaction when the grandchild bore the mother's surname. This, coupled with many highly educated women only daring to expect their husbands to "be able to earn money, not gamble, and not have affairs", led Jiang Lai to exclaim that gender equality awareness remains very fragile.

Beyond facing internal family pressures, mothers are also surrounded by a fiercely competitive education system. Shen Yang herself was once caught in the cycle of investing time and money in her children until she realized the absurdity of making her child the absolute center of the family universe. Her awakening came during a piano lesson, where she recognized the need to prioritize her personal needs to reduce the stress of raising children. Her family later declined an invitation for her child to join a fencing team, despite being selected, simply because the training location 8 km from home would disrupt their family routine.

"The new philosophy is that the family is not just a place to serve the child, but a unit that needs to ensure the healthy development of all members", the professor stated.

|

Professor Jiang Lai (far right) with her husband and son. Photo: HK01

However, for individual mindsets to change, society must transform its systems. Scholars emphasize that reproduction should not merely be a policy slogan, a national duty, or an idealized story detached from reality. Instead, it must be viewed through the lens of personal experiences and the practical difficulties families face. Professor Jiang Lai affirmed: "Our view is simple: only when you protect women in the workplace will they dare to have children at home".

Policies cannot solely focus on subsidies but must protect women's rights and status in the workplace. Additionally, there needs to be increased investment in medical research, such as reproductive risks after age 35, to build a truly supportive care system.

Jiang Lai, who once had a child while "unprepared", concluded: "Having a child is not like opening a mystery box; you need to understand everything clearly before choosing whether or not to have one".

Binh Minh (According to HK01)