"We were speechless," the mother recounted. "We love our son so much, and to be treated like this felt like a betrayal."

The text messages between their 8th-grade son and his friends also left the couple stunned. The boy showed no hesitation in using profanity and insulting his teachers and parents.

Le said she had never cried so much in her life. In her distress, she sought advice from a parent group, only to be further hurt by judgments like "Spoiled brat" and "Children react based on their parents' behavior."

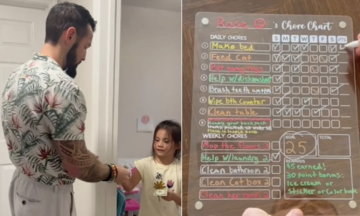

|

Giving offensive nicknames to parents is not uncommon, but it indicates underlying problems in the parent-child relationship. Illustration: Sohu. * |

Kim Thanh, a psychologist in Hanoi with years of experience counseling parents and children, believes that children giving offensive nicknames to their parents is quite common, especially during adolescence. This is a period when they are developing emotionally, testing boundaries, and reacting to pressures from family or school.

Phan Van Le Son, a master's student at IPU Berlin, Germany, explains that this phenomenon is often referred to as covert resistance or identity distancing in psychology.

"Many teenagers use shocking or disrespectful nicknames for their parents as a way to gain control in a world where they often feel voiceless," Son says. This is particularly prevalent among introverted teens who rarely share their feelings and are going through a phase of psychological separation from their parents to establish their own identity.

Other contributing factors include peer influence and online language, which normalize vulgar nicknames and can even facilitate social integration within peer groups.

From the perspective of attachment theory, Dr. Tran Kieu Nhu, a researcher on children and families at Leiden University (Netherlands), explains that the early relationship between a child and their primary caregiver forms either a secure or insecure attachment (including avoidant, anxious, and disorganized).

"Children with secure attachments, even when experiencing negative emotions towards their parents, are still capable of direct communication and dialogue. Giving offensive nicknames, if it happens, is usually playful and within limits," Dr. Nhu explains. "But for children with insecure attachments, this behavior can be a way of signaling distress."

Dr. Nhu recalls working with a boy whose mother was gentle and never resorted to scolding or physical punishment. In response, he gave her the "cold shoulder" and an offensive nickname.

After in-depth conversations, the expert realized the mother often used negative emotions to control her son. Whenever he disobeyed, she would lament, saying things like "You're hurting me so much." This communication style made the boy feel manipulated and unable to be himself, ultimately leading to his reaction.

Many parents often say "Kids these days have it too easy" or "They're spoiled" when talking about Gen Z teenagers and beyond. In her book *The Price of Privilege*, American psychologist Dr. Madeline Levine, with 35 years of experience working with children and parents, concludes that despite material advantages and educational opportunities, children of every generation grapple with psychological issues, from depression and rebellion to substance abuse and self-harm, at higher rates than any previous generation.

Humans have always had the need for autonomy, developing their abilities, and building relationships with others.

But within the group of children considered "spoiled," Dr. Madeline found that well-meaning parents were inadvertently hindering their children's development of self. This happens when parents apply pressure, emphasize superficial measures of success, are overly critical, indifferent, or impose their own emotions.

When children are not given the opportunity to experience and shape their own identity, rebellious behavior, offensive nicknames, or silent withdrawal may emerge. And as long as these needs remain unmet, the "psychological pandemic" among young people will continue to escalate.

Experts agree that such manifestations should not be equated with "disrespect" or "being spoiled." Language is just the surface; the focus should be on the motivations, emotions, and needs behind the behavior.

"What children write or save on their phones or social media doesn't reflect their entire being. It's just a snapshot of their mood at a particular moment, sometimes fueled by negative emotions or peer influence," Son says.

He advises that instead of reacting with criticism or punishment, parents should view this as a signal to listen and understand what difficulties their child is facing and what they need, thereby learning how to reconnect.

"Le, forgive your son and yourself," the expert advises. "Consider the nickname as a message to reflect on your relationship: Does your son feel safe, heard, and connected? What emotions is he experiencing, what difficulties is he facing, and what deeper needs is this behavior ultimately trying to fulfill?"

The same evening the incident was discovered, Le's husband spoke directly with their son. The boy expressed remorse. In a letter to his parents, he apologized, explaining that his language was influenced by his close friend, that it had become a habit, and that it made him feel accepted by the group. He saved those nicknames right after being scolded by his mother, which left him feeling resentful.

"Reading his letter, I realized he's still my son, and I understood why he has this other side," Le shared.

The mother wrote a letter back to her son. "In the letter, I expressed my desire to become a trustworthy mother so that he would open the door to this other version of himself," she said.

Phan Duong