Nguyen Do Dung, CEO of enCity, a global urban planning consultancy, shared his insights with VnExpress regarding the re-establishment of Ho Chi Minh City's Department of Planning and Architecture. Dung, who lectures on urban planning at the National University of Singapore and has worked on major projects in over 10 countries, including Ho Chi Minh City's 2040 Master Plan, emphasizes the need for a shift in approach.

|

Nguyen Do Dung during his interview with VnExpress on 17/9. Photo: Quynh Tran |

Nguyen Do Dung during his interview with VnExpress on 17/9. Photo: Quynh Tran

Dung believes a dedicated agency is essential for shaping the long-term development of a complex metropolis like Ho Chi Minh City. Re-establishing the Department of Planning and Architecture is a logical step, providing a central authority to oversee the "big picture." However, he stresses that this requires a new mindset and mechanisms for effective implementation.

Having worked on several major planning projects for the city, Dung observed that other departments often default planning responsibilities to the Department of Planning and Architecture. This is problematic, as no single entity fully grasps the multifaceted challenges and potential across all sectors.

He advocates for a collaborative approach where the Department of Planning and Architecture acts as a "conductor," coordinating input from other departments, each contributing their expertise. The Department of Education, for example, is best positioned to understand future school needs, while the Department of Industry and Trade can project industrial zone requirements, and the Department of Health can assess hospital needs. Current planning often relies on standards that may not reflect reality. Standards represent an ideal, while the actual work of each department involves navigating the path from the present to that ideal—a journey requiring extensive coordination.

Dung suggests incorporating practical needs from various departments into planning objectives. The goal should be tangible outcomes: sufficient schools, ample green spaces, clean air, uncongested roads, and minimized flooding—not just meeting abstract criteria on a blueprint.

Addressing the criticism that Ho Chi Minh City's development has resembled an "oil spill," leading to overloaded infrastructure, traffic congestion, and a lack of public spaces, Dung acknowledges some validity but emphasizes the need for a broader perspective. Urban planning involves two stages: formulation and implementation. Ho Chi Minh City's current situation reflects both. Some plans haven't accurately captured real-world needs, while others, though sound, have suffered from weak implementation.

Dung highlights Singapore as a model where planning agencies possess tools for implementation. For example, when designating a financial center or tourist area, the planning agency can bid on land and seek suitable investors. Success earns them a share of the profits. This approach links planning and implementation. Unrealistic plans won't attract investors, leading to stalled projects. Conversely, feasible plans draw resources, transforming blueprints into vibrant urban spaces.

|

Over 1,100 residents in the Ga-Gao Market area, Cau Ong Lanh ward, have endured cramped, damp conditions for years due to stalled projects. Photo: Quynh Tran |

Over 1,100 residents in the Ga-Gao Market area, Cau Ong Lanh ward, have endured cramped, damp conditions for years due to stalled projects. Photo: Quynh Tran

In Ho Chi Minh City, the Department of Planning and Architecture relies heavily on other agencies like construction, industry and trade, finance, and agriculture and environment. When plans fail, pinpointing the cause amidst complex regulations and inter-agency processes is difficult.

Dung believes the Department of Planning and Architecture needs both collaborative mechanisms and implementation tools, coupled with accountability. Quoting the Prime Minister, "the biggest bottleneck is the system, but the system is also the easiest bottleneck to remove because we created it." Empowering the Department of Planning and Architecture is achievable.

He cites Singapore's Housing and Development Board (HDB), which controls land, capital, and even the construction materials market, keeping housing prices at 4 times the average income, compared to 30 times in Ho Chi Minh City. This enables the HDB to meet 80% of housing demand, allowing young couples to afford homes within a few years of work, with government support.

Dung advocates for shifting from managing processes to managing outcomes, allocating budgets and setting objectives while leaving implementation methods to the responsible agency. They can work independently, hire consultants, or employ top experts, as long as objectives are met ethically. The desired outcome is a clean, safe living environment with accessible parks, affordable quality housing, schools, and playgrounds – not just adherence to procedures.

After merging with surrounding provinces, Ho Chi Minh City's area has tripled to nearly 7,000 km2, and its population has grown by almost 50% to 14 million. This presents new challenges for urban planning, requiring a balance between immediate concerns and long-term vision. A good plan anticipates the future, sometimes envisioning things that seem unbelievable or even draw opposition today. Phu My Hung, planned in the 1990s, is a prime example. Few believed it could become the modern center it is today, taking over 30 years to materialize.

The expanded Ho Chi Minh City faces greater complexity, addressing not only the urban core but also the vast, sprawling metropolitan area extending into Binh Duong, blurring boundaries. It also needs to connect distant, independent cities like Vung Tau, Long Hai, and Phu My.

While the scale and diversity pose challenges, they also offer advantages. The city now has more land and less local bias, allowing for optimal resource allocation in infrastructure projects.

|

Heavy rain on 5/8 caused widespread flooding, leaving many vehicles stranded. Photo: Quynh Tran |

Heavy rain on 5/8 caused widespread flooding, leaving many vehicles stranded. Photo: Quynh Tran

Previously, limited land forced the city to allocate industrial land in flood-prone areas like South Nha Be and West Binh Chanh to attract foreign direct investment. Now, with additional land in Binh Duong and Ba Ria-Vung Tau, these areas can be prioritized for ecological urban development and water retention. This promotes a more sustainable and efficient development model.

Unified coordination is another advantage. Past environmental conflicts in border areas, like the Ba Bo canal dispute between Ho Chi Minh City and Binh Duong, can now be addressed within a single administrative framework, balancing industrial development with environmental protection and water quality.

The merger also facilitates enhanced infrastructure connectivity. Metro Line 2, initially planned to terminate in Hoc Mon-Cu Chi, could extend to Thu Dau Mot, improving Binh Duong's connectivity and linking Hoc Mon-Cu Chi to two major urban areas. Planning for the Saigon River can now consider both banks, enhancing riverside landscapes, water quality, and flood control.

Dung notes that Vietnamese urban planning is often overly cumbersome, with Vietnam being perhaps the only country to both legalize and formalize master plans. The expectation to encompass everything leads to years of drafting and further years of revisions for even minor changes. The city's chairman recently called for a streamlined, one-year planning process to maximize implementation time.

Dung suggests a shift in mindset. No master plan can accurately predict 20-30 years into the future. The overall plan should be flexible, allowing adjustments during detailed implementation. Singapore's master plans are strategic frameworks, not rigid legal documents. The chief architect interprets and adapts them as needed. In contrast, Vietnam's master plans serve as both guidelines and legally binding technical documents. A road planned as straight but needing a curve due to a historical building requires lengthy revisions, wasting time and opportunities.

For the expanded Ho Chi Minh City, simply combining the three old master plans is insufficient. The city needs to redefine its overall development structure, identifying industrial zones, ecological preservation areas, main infrastructure routes, and metro lines. Sticking to old plans with minor adjustments saves time but wastes resources.

|

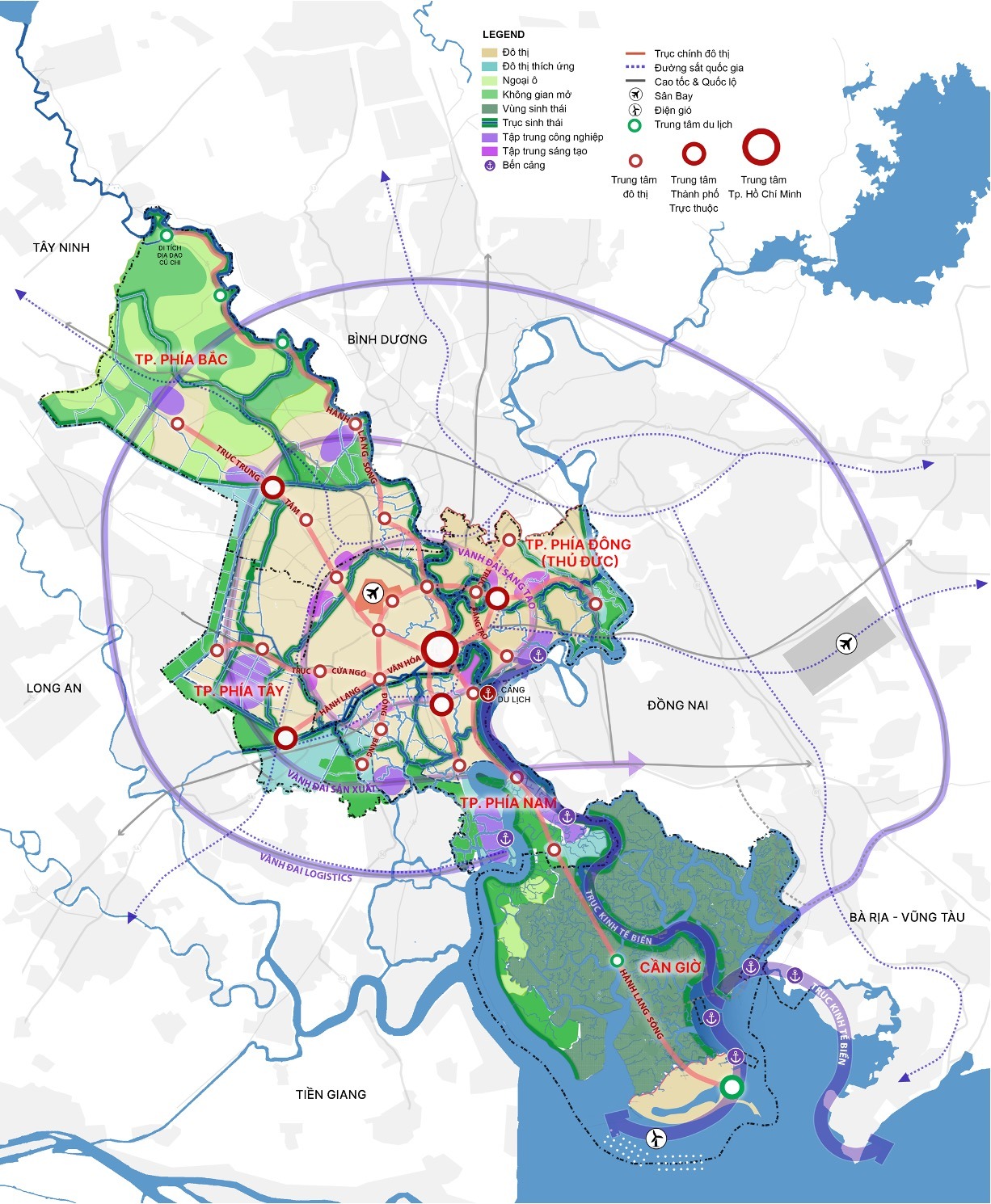

Spatial development plan for Ho Chi Minh City in the draft Master Plan to 2040, with a vision to 2060. This predates the merger with Binh Duong and Ba Ria-Vung Tau. Source: Consulting Group of the National Institute of Urban and Rural Planning (VIUP) - enCity and Ho Chi Minh City Urban Planning Institute (UPI) |

Spatial development plan for Ho Chi Minh City in the draft Master Plan to 2040, with a vision to 2060. This predates the merger with Binh Duong and Ba Ria-Vung Tau. Source: Consulting Group of the National Institute of Urban and Rural Planning (VIUP) - enCity and Ho Chi Minh City Urban Planning Institute (UPI)

Dung proposes developing a new strategic framework to guide investment and development, running parallel to the formal plan adjustment process. This framework doesn't need excessive detail but should answer key questions: What development model will the expanded city follow? Where will population and infrastructure shift? This framework, with a 100-year vision, should be developed by a task force led by the Department of Planning and Architecture, comprising capable officials from various departments and supported by experts with both international and local experience. This collaborative model ensures efficient and far-reaching urban planning.

Le Tuyet