For decades, a university degree from prestigious institutions like Stanford was considered an essential "ticket" into US tech corporations. The success of many prominent figures, such as LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman and Google co-founder Sergey Brin, reinforced the belief that an academic path was a reliable measure of competence and career prospects in the field.

However, that perception appears to be changing. "We used to hire many people with excellent academic records, but we have also hired many without bachelor's degrees. They can figure things out in their own way," Brin shared with Stanford students in December 2025.

Brin's statement garnered attention because Google has historically been known for prioritizing academic backgrounds in its recruitment, especially during the boom in tech talent in the US.

Nevertheless, the company has begun adjusting its approach to better suit today's younger workforce. Data from the Burning Glass Institute shows that between 2017 and 2022, the percentage of job postings at Google requiring a university degree decreased from 93% to 77%.

|

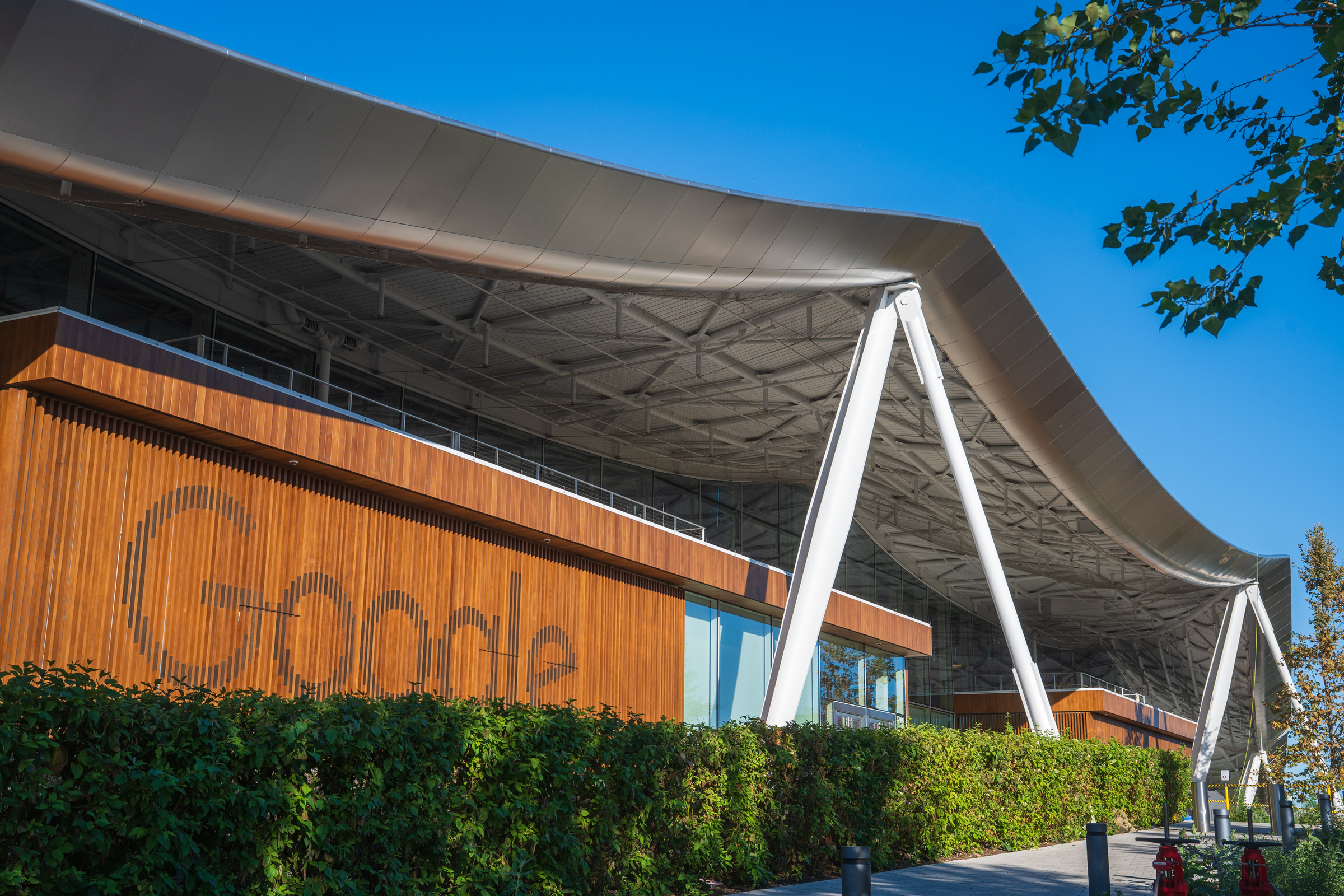

The Google headquarters in Mountain View, California, December 2025. Photo: Reuters

Google is not an isolated case. Companies like Microsoft, Apple, and Cisco have also reportedly lowered their university degree requirements for candidates in recent years.

This shift is particularly significant for Gen Z, the generation that grew up with the internet. Today, many young people acquire skills through personal projects, short courses, professional certifications, or early work experience, rather than pursuing a university education.

US companies becoming more flexible about degree qualifications provides this group of workers with more opportunities to access companies once considered exclusive to those with strong academic profiles.

The Financial Times refers to this workforce as "new collar," distinguishing them from older concepts of two main labor groups: "white collar" office workers and "blue collar" manual laborers.

The "new collar" group in the US consists of individuals hired and promoted based on skills, regardless of whether they hold a university degree. This phenomenon is not tied to specific job positions but reflects how businesses select people, from software development and data analysis to sales and operations management. The common thread is that workers' practical skills and experience are prioritized over their academic qualifications.

According to Bridget Gainer, Aon’s global head of external affairs and policy, businesses need to change their hiring policies to clearly define the skills truly necessary for each position, rather than "just demanding candidates study at better schools than the rest." Aon is a leading global professional services and risk management firm headquartered in the UK.

Many US entrepreneurs in other fields have expressed views similar to Sergey Brin.

Jamie Dimon, CEO of financial giant JPMorgan Chase, stated in 2024 that education does not equate to job performance. "I do not think that attending an Ivy League school or having high grades means you will be a good employee," Dimon shared.

Alex Karp, CEO of defense corporation Palantir, who holds three degrees, including a law degree from Stanford, was even more direct. "Once you come to Palantir, you are a Palantir person. Nobody cares about other things," Karp commented on the corporation's degree policy.

Michelle Hodges, vice president of global human resources at US airline United Airlines, said the company is also adjusting its recruitment approach. The company must retrain its own recruiting teams, helping them identify and properly assess candidate skills, rather than heavily weighing degree qualifications as before.

Matt Sigelman, president of the Burning Glass Institute, a non-profit organization in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, US, specializing in research on the future of work and the labor market, believes that a university degree is gradually becoming "a less effective signal" for evaluating candidate competency.

According to him, over-reliance on degrees not only narrows the labor supply but also hinders the career development opportunities of many talented individuals. "We are tying our own hands by creating personnel shortages in fields that do not lack candidates," he said.

By Ha Linh (Based on Times of India, Fortune, Financial Times, Forbes)