Srinivasa Ramanujan (1887-1920), an Indian mathematician, is renowned for thousands of astonishing theorems. Notably, he often concluded complex formulas without proof, yet these became foundational for many advanced areas of physics and mathematics.

Ramanujan was born into a poor Hindu family in Tamil Nadu. His father worked as an accountant, and his mother sang hymns at the local temple. At seven, a smallpox attack nearly claimed his life, while his three younger siblings were not as fortunate.

In elementary school, Ramanujan studied Tamil (his mother tongue), English, geography, and mathematics. He achieved the highest exam scores in the district in 1897, subsequently attending an English-medium high school.

He quickly surpassed the curriculum, beginning to self-study fundamental theorems in trigonometry, geometry, algebra, calculus, and differential equations using an advanced book he found. Almost entirely lacking an academic environment, Ramanujan developed his mathematical thinking in solitude, with only a few rare books and hours of solitary contemplation.

He received a university scholarship in 1904. However, Ramanujan subsequently lost interest in everything except mathematics. As a result, he failed most subjects and lost his scholarship. In 1906, he enrolled in other institutions, but the pattern repeated, and he did not obtain any post-secondary degrees.

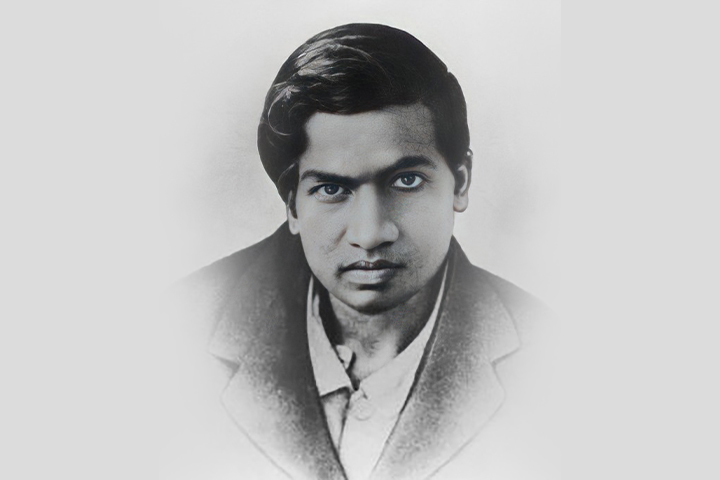

|

Srinivasa Ramanujan. Photo: CFAL India

In 1909, after an arranged marriage by his mother, Ramanujan immersed himself in mathematics day and night, often forgetting to eat or sleep. The responsibility of caring for his parents and wife then fell upon him, forcing him to seek a livelihood. He relied solely on meager earnings from tutoring students. Despite being so poor that he only had enough paper to write down results, solving problems on slate, Ramanujan continued his diligent research.

A turning point arrived in 1912 when he sent a letter to G.H. Hardy, a renowned mathematician at Cambridge University, England, filled with unusual formulas on continued fractions. Hardy frequently received numerous letters from around the world daily. Thus, at first, he merely glanced at Ramanujan's letter—from a clerk without a university degree. He initially thought the author was either a fraud or a madman.

However, upon reading the letter more carefully, Hardy realized it was written by an extraordinary genius. The theorems presented brilliant ideas, though heavily based on intuition rather than preliminary steps—beyond Hardy's own comprehension.

Hardy then arranged a scholarship for Ramanujan at Cambridge University. In 1914, Ramanujan traveled to England, where he studied and collaborated with Hardy for 5 years.

This period marked Ramanujan's immense productivity, during which he published over 30 significant papers. His works covered a broad range in pure mathematics, including continued fractions, elliptic functions, and partition theory.

One of his most unique research directions involved highly composite numbers—numbers possessing more divisors than any smaller number (e.g., 12, 24, 360).

He discovered that when a highly composite number is expressed as a product of prime numbers, the exponents consistently decrease in order.

However, throughout his time in England, Ramanujan struggled with illness. He returned to India in 1919 in poor health. Ramanujan intended to accept a university professorship in Madras upon recovery, but this did not materialize. He passed away a year later, reportedly from tuberculosis, at just 32 years old.

Before his passing, he left a notebook containing over 100 pages on mock theta functions. Ramanujan never explained how he discovered them, but a century later, scientists recognized these functions as key to understanding black hole entropy and string theory in modern physics.

Over 100 years have passed, and the world is still striving to "catch up" with Ramanujan's vision. The legacy of that impoverished young Indian continues to shape the future of human science.

Khanh Linh (Sources: Ebsco, Swarajya, Quanta Magazine)