According to historian Janetta Rebold Benton in her book "Understanding Art," photography emerged nearly 200 years ago following a series of inventions by French and British scientists. Initially, it was purely a scientific field, with cameras simply used to record reality, not considered an art form.

In 1864, the field turned a new page when a woman nearing 50 unveiled her soft-focus photographs. That woman was Julia Margaret Cameron, a British artist who pioneered the use of photography as a fine art.

Coinciding with the exhibition "Julia Margaret Cameron: Arresting Beauty" at The Morgan Library & Museum (New York), Artnet published an article looking back at Cameron's career. Written by veteran journalist Sarah Cascone and published on 10/9, the article hails Cameron as "the Victorian woman who changed photography".

Born Julia Margaret Pattle in 1815 in British India, Cameron was educated in France and spent most of her life during Queen Victoria's reign, hence the label "Victorian." In 1835, she moved to the Cape of Good Hope (South Africa) to recuperate from a serious illness. There, she met two men who would change her life: Charles Hay Cameron, her future husband, more than 20 years her senior, and astronomer John Herschel, a lifelong friend who introduced her to photography.

Herschel, also a photographer, invented the cyanotype process, a blueprinting method widely used in technical drawings. In 1839, he wrote to Cameron about cameras. Three years later, he gifted her 12 calotype and daguerreotype (images printed on metal plates, invented by Louis Daguerre) photographs. This was her first encounter with photographic images.

|

Portrait of Julia Margaret Cameron by her son, photographer Henry Herschel Hay Cameron, in 1870. Photo: Victoria & Albert Museum |

Cascone describes Cameron's passion for photography as a slow but unexpected development. Initially, she simply posed for portraits, keeping the photos in family albums. Later, she observed photographers at work, even hiring one to photograph her neighbor and friend, the poet Alfred Tennyson, at his home. She then practiced developing other people's negatives.

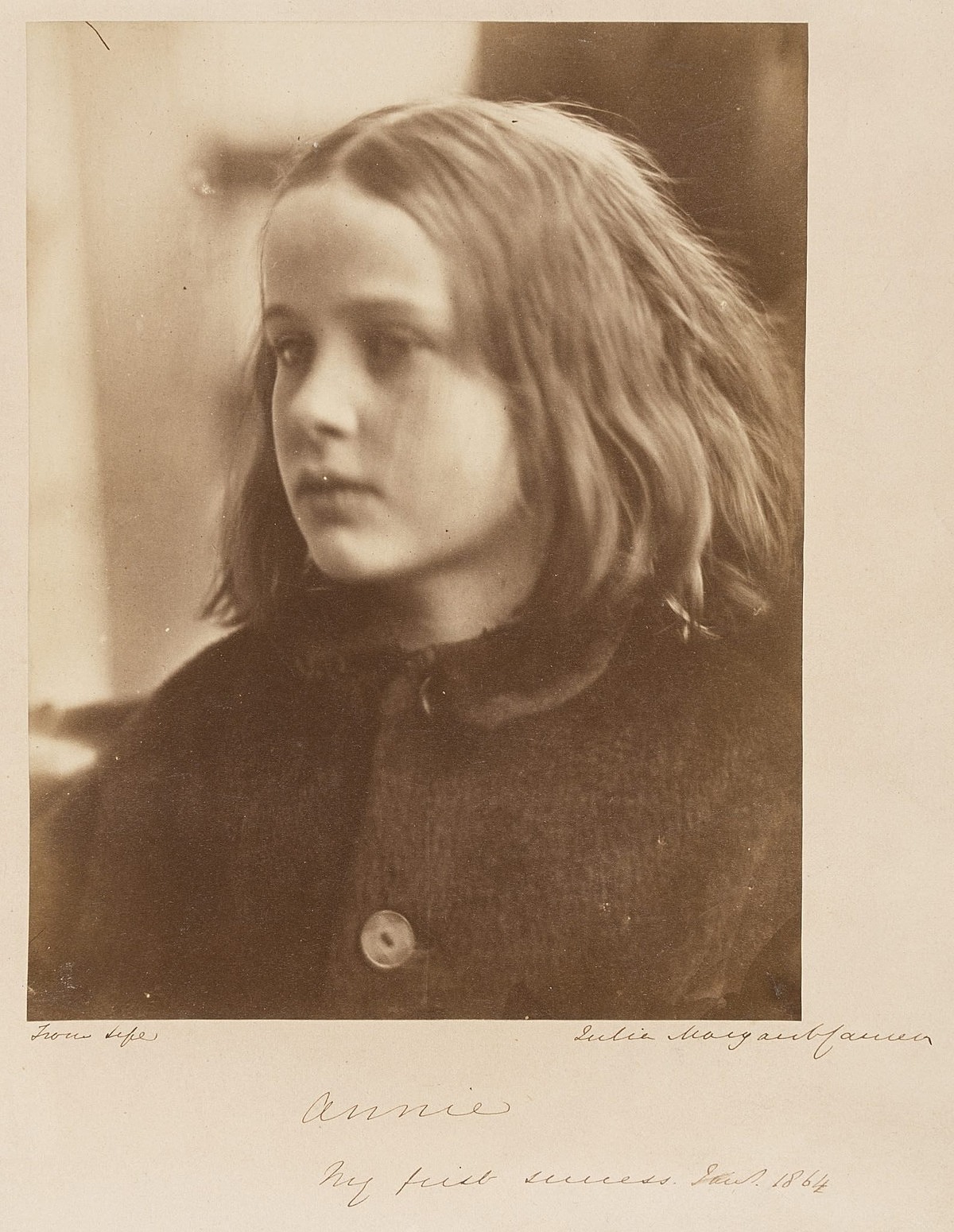

At Christmas 1863, Cameron received a camera from her daughter, marking the start of her new career. Within a month, she created her first soft-focus work, featuring her young neighbor Annie Philot. Cameron called it her "first success".

|

Portrait of Annie Philot (1864). Photo: Victoria & Albert Museum |

According to Artnet, to achieve her signature soft-focus effect, Cameron deliberately left streaks, swirls, ripples, and even fingerprints on the coating of her glass plate negatives. She then dipped the glass in silver nitrate, quickly placed it in the camera, and exposed it before the coating dried. She coated photographic paper with a glossy emulsion of egg white and salt, sensitizing it with silver nitrate and UV light. Once dry, she placed the paper on the negative and exposed it to sunlight to develop the image. Finally, she toned and washed the print to fix it.

Morgan assistant curator Allison Pappas notes that Cameron's photographic process required skill and dexterity, explaining that capturing and developing a single image could take two days.

Amidst the burgeoning photography scene in 1860s Britain, Cameron held her own exhibitions shortly after embarking on her career and became a member of the Photographic Society of London. However, her work was controversial. At an 1864 exhibition, judges remarked that her technique would improve if she learned to use the equipment properly.

Yet, Artnet argues, these "flaws" created her unique style, securing her distinct position in the field and enduring popularity. Instead of adhering to the prevailing sharp-focus standards, she drew inspiration from art history, employing chiaroscuro (strong contrasts between light and dark) and sfumato (blurring outlines to create a hazy effect), techniques popular during the Renaissance and Baroque periods and developed by Leonardo Da Vinci.

* Some of Julia Margaret Cameron's works

Cascone argues that for Cameron, "photography wasn't just a mechanical means of soullessly recording the world." Her photographs were "fully realized works of art," often illustrating scenes from poetry, literature, drama, mythology, and art history.

Cameron also photographed leading cultural and intellectual figures of her time, including Charles Darwin, the "father of evolution," poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, and Alice Liddell, the inspiration for the novel "Alice in Wonderland" (1865). According to Cascone, Cameron left behind "a legacy that is both historically fascinating and aesthetically striking".

|

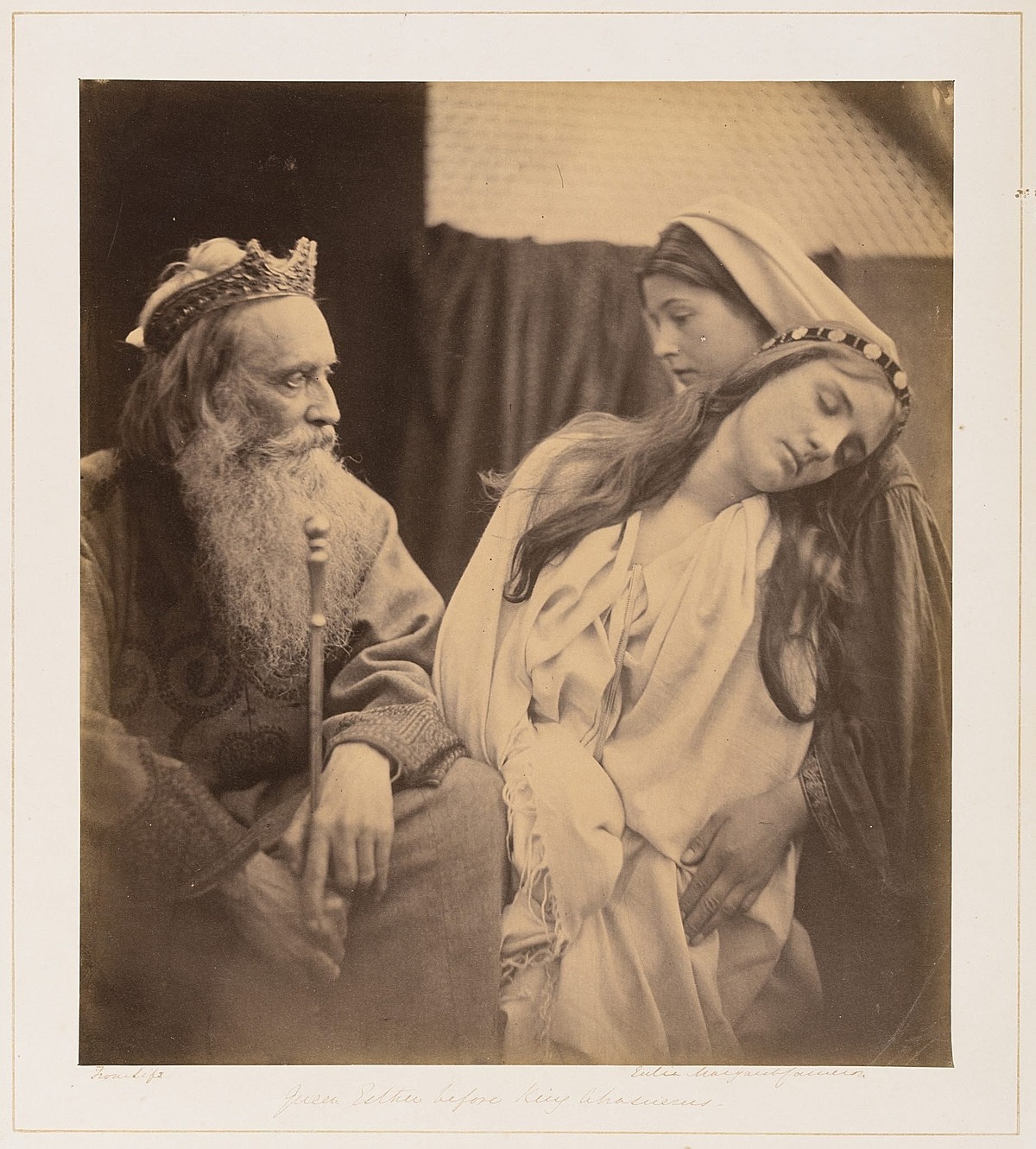

"King Ahasuerus and Queen Esther in Apocrypha" (1865) depicts a scene from a biblical play. This is one of the artist's most dramatic works. Photo: Victoria & Albert Museum |

In 1865, Cameron began selling her photographs through the art dealer P. & D. Colnaghi, now the oldest commercial art gallery in the world. She also exhibited at the South Kensington Museum, London (now the Victoria & Albert Museum, or V&A), which acquired 63 of her prints. The V&A purchased the photographs as artworks, not documents. Later, Cameron became the institution's first artist-in-residence, with a dedicated portrait studio within the museum.

Despite considering herself an "amateur" and primarily photographing acquaintances rather than clients, Cameron sought to commercialize her work due to her family's financial constraints. Her husband's investment in a rubber plantation in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) proved unprofitable. "Cameron and Colnaghi priced her photographs very highly. She put a lot of work into them. Unfortunately, she never really broke even. It was an expensive undertaking, and she often gave away more prints than she sold," Pappas explains.

In 1875, the Camerons moved to Ceylon, unable to afford life in Britain. This decision effectively ended her 11-year photography career. The high cost of materials and unsuitable weather conditions in Ceylon likely contributed to her retirement. She passed away there 4 years later.

Reflecting on Cameron's legacy, Cascone concludes that although she wasn't the first to stage photographs or capture "elaborate subjects for photographic effect" instead of everyday moments, Cameron succeeded in demonstrating that artists could imbue their images with emotion.

Trinh Lam (adapted from Artnet)