Released in August, the book offers glimpses into the lives of Vietnamese volunteer soldiers on the southwestern border front, during and after the war. Instead of focusing on the battles, Doan Tuan tells stories about his comrades through everyday life. The book reveals the personalities and emotions of each soldier. Writing about them is Tuan's way of repaying a debt to the past, ensuring his comrades are not forgotten.

In the introduction, Tuan explains the book's title. Smoke was the first thing he saw upon returning home after 5 years of fighting: "Smoke from the Central Highlands. Smoke fragrant with the scent of fields and gardens. [...] The homeland appeared not with flags, not with slogans, but with that faint blue smoke."

Yet, those who returned could not leave the war behind. Deeply etched in Tuan's memory is the "incense-less cemetery" where he buried his comrades. He felt "those deaths still silently emitted smoke towards the horizon. Smoke you couldn't see, but still smoldered in the memories and guilt of the living." Later, seeing the smoke of peaceful life rising from across the country, he remembered those who had fallen. Smoke became a symbol of remembrance. Thus, he "wrote to hold onto them, so they don't fade into silence, aren't forgotten amidst the bustling life. Writing, like offering an invisible stick of incense."

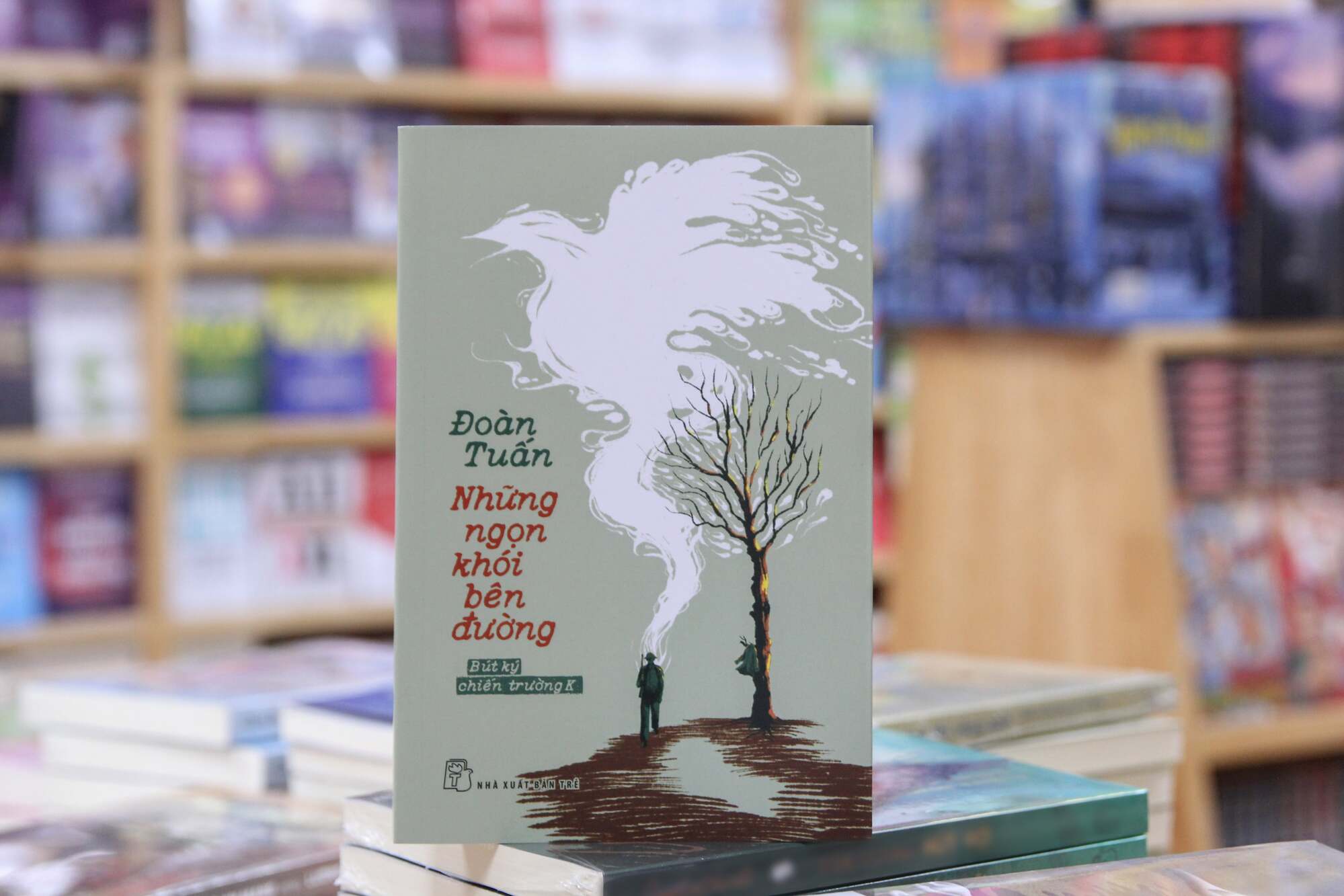

|

Cover of "Those wisps of smoke along the road." Photo: Tre Publishing House |

Cover of "Those wisps of smoke along the road." Photo: Tre Publishing House

The essays in "Those wisps of smoke along the road" revolve around Battalion 8, Regiment 29, Division 307 of the Vietnamese volunteer army in northeast Cambodia, particularly Preah Vihear province. The stories follow their journey from guarding posts in Gia Lai - Kon Tum to crossing the border for international duty, crossing the Mekong River in pursuit of Pol Pot's forces, then moving to Preah Vihear to protect the Cambodian border and prevent Pol Pot's incursions.

Tuan tells stories of soldiers facing the harsh realities of war, bearing physical and emotional scars. Yet, they still laughed, sang, played jokes, and yearned for peace for both countries. Amidst the harshness, ordinary moments became precious: "From the 27th day of Tet, the enemy constantly shelled us. They knew it was Tet, so they were determined to prevent our celebrations. They blocked our supply routes and shelled us. But in the bunker, Liem still made alcohol. And taught me how to distill it. Despite the shelling, the alcohol still flowed."

Tuan explores the "human" side of the soldiers. In "The fermented fish paste addict," a scout named Sinh loved Khmer fermented fish paste, often trading gifts for it, eventually falling for a Khmer woman. He said, "You guys talk about fighting in Cambodia like it's all booms and bangs. But me, I have a fighting story, a love story, and even a fermented fish paste souvenir. That's what being a soldier on Battlefield K is all about!"

Through everyday stories, the book reveals not only camaraderie among soldiers but also the bond between the Vietnamese army and the Khmer people. They exchanged goods, gifts, conversations, and sometimes even romantic feelings. Vietnamese soldiers would sleep in villagers' homes, asking for a fish here, an onion there. There was no hatred or discrimination. Both shared a desire for peace: "The Vietnamese volunteer army gave the Cambodian people their blood and bones without hesitation." Even towards the enemy, there was tolerance: "We didn't hate Pol Pot's soldiers. Before they were soldiers, they were civilians. Farmers. Working in the fields. The brutal Pol Pot regime forced them into the army. Soldiers everywhere suffer. Sharing with them, who knows, maybe we could change their minds?"

Tuan also depicts the war's brutality: the burning thirst, lurking diseases, ubiquitous landmines, bloodshed, and horrific wounds. Death was a heartbeat away.

Having witnessed countless comrades die, Tuan tells their stories, how they fell, preserving their short but bright lives. These are "Silent deaths, but forever sacred!" He writes: "A soldier's life can be very short. Only 3 months in the army. Just a few days at the border. Not yet knowing all the names in his squad. Not yet having written his first letter home from the battlefield. And died in his first battle. A painful death." Burying comrades became routine. The soldiers grew accustomed to it, but they did not forget.

After the war, returning home and reunions are frequent themes. The book includes many such encounters, even at gravesides. Like other veterans, Tuan often visits the cemetery where his comrades lie, to offer incense. At the graves, he sees his friends again, aged eighteen or twenty.

He also thinks about the fallen comrades whose remains haven't been found, or those who have been found but remain unidentified. Despite efforts to bring them home to their families, time and losses are obstacles. Tuan remembers them, conveying the gratitude of the living: "Though nameless, no one forgets you - my comrades. You died so I could live and return."

|

Author Doan Tuan. Photo: Vietnam Writers' Association |

Author Doan Tuan. Photo: Vietnam Writers' Association

A screenwriter, Tuan paints portraits of soldiers with concise, vivid language, capturing their spirit through evocative details. The book contributes to the body of work on Vietnamese soldiers, intertwined with the nation's history of struggle for independence and defense.

Doan Tuan, 65, a former student at Hanoi National University's Literature Department, graduated from the USSR State Institute of Cinematography (VGIK) in 1991. He fought in Cambodia from 1978 to 1983. His screenplays include "Women's Alley" ("Love story in a narrow alley"), "The Golden Key," "Letter Street," and "Legend of Quan Tien." He has also published books such as "Love Spell," "Spring Prelude," "Land Outside the Homeland," "Season of Premonition," and "That Season of War."

Khanh Linh