Although presented as a novel, Ocean Vuong's latest book, "The Emperor of Gladness" (EG), feels more like an autobiography—a diary reimagined through the lens of fiction. Following the resounding success of "On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous," EG continues the narrative of the Vietnamese-American characters introduced in his debut novel.

However, the focus shifts from the family's reasons for leaving Vietnam to their experiences in their new American environment. While the previous book revisited the family's fragmented history, EG focuses squarely on the present-day United States—a present depicted in a less-than-ideal light. The setting encompasses suburbs, interstates, fast-food restaurants, big-box stores, and monotonous roadside houses, all situated within a ravaged natural world. The characters' lives are not marked by quiet desperation, as Thoreau once described the lives of the masses, but by an open and clamorous despair.

|

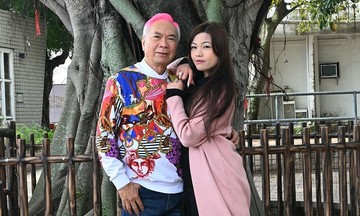

The cover of Ocean Vuong's "The Emperor of Gladness," released in the US on 13/5. According to Nha Nam, the publisher, the Vietnamese edition will be released in August, translated by Khanh Nguyen. Photo: Penguin Press |

The cover of Ocean Vuong's "The Emperor of Gladness," released in the US on 13/5. According to Nha Nam, the publisher, the Vietnamese edition will be released in August, translated by Khanh Nguyen. Photo: Penguin Press

The story unfolds in the fictional town of "East Gladness"—an imagined locale on the fringes of society on the American East Coast, not unlike where the author grew up. Hai, clearly another version of Ocean Vuong, is a 19-year-old Vietnamese-American man whose life is at a standstill. Along with a loving but strained relationship with his mother, he has an aunt in jail for insurance fraud, an elusive cousin, and the ever-present memory of his deceased grandmother. He also grapples with opioid addiction and the suicide of his lover. At the beginning of the story, he has dropped out of college and is consumed by grief, contemplating ending his life. An older woman, Grazina, intervenes when she sees him about to jump off a bridge.

Grazina, a lonely and impoverished Lithuanian-American, offers Hai a place to stay. More importantly, she gives him a job to distract him from his pain. The kind woman suffers from Alzheimer's and is haunted by horrific memories of World War II in Europe. Almost by chance, Hai becomes Grazina's live-in caretaker. The empathy between these two strangers, both living at the bottom of society, forms the emotional core of EG.

Another layer of emotional depth lies in the staff at the local fast-food restaurant, Home Market Chicken, where Hai works. The camaraderie of the Home Market team, and Hai's relationship with the traumatized European woman who reminds him of his grandmother, are central to the narrative. There's Wayne, a portly cook who lost his son; Maureen, an alcoholic conspiracy theorist with a kind heart; a harsh manager known as "BJ"; and Sony, Hai's cousin, a man haunted by American history, also kind but burdened by a difficult past. After introducing this group of marginalized characters, Ocean Vuong presents readers with 250 pages of somewhat chaotic descriptions of the various incidents in the dead-end service industry to which the characters cling.

Like Grazina, the Home Market staff are vividly portrayed, but their personalities don't develop much. Their adventures with Hai are sometimes humorous, sometimes arduous, but at times also lengthy and tedious.

A lively chapter describes Wayne finding extra work for the group at a slaughterhouse. They are paid to butcher a type of pig called the "emperor pig"—the name Ocean Vuong uses for the book's title. "The Emperor of Gladness," as the reader perceives, refers not only to Hai but also to his group of misfit friends, "emperors" in a reversed sense—both helpless like the pigs and suited to the "slaughterhouse blade" of American society. "Gladness" is not simply the name of the fictional town but also an ironic indicator of what America doesn't allow these suffering characters to feel, except for a few fleeting, precarious moments.

On the one hand, the author enjoys evoking the physical nuances of people and objects, the subjective feeling of places and seasons; many passages are written almost like prose poems, rich in adjectives and skillful metaphors. On the other hand, this style sometimes clashes with the grunge humor he tries to create from the Home Market staff's moments of joy, or with his sharp perspective on American social issues.

This voice also feels somewhat discordant when expressing the compassion the writer wants to infuse into the characters' lives. Hai's choked-up narration about his relationship with his mother shows that maternal love persists through hurt, loss, and shattered expectations. Hai's memories of his grandmother, or the close relationship he still has with his cousin Sony, are similar. Clearly, Ocean Vuong is trying to evoke deep emotions that emanate from the heart and endure even when life is incredibly bleak. However, the author's passion for detailed descriptions often gets in his way. Ocean Vuong tends to lead his characters through all sorts of situations, scrutinizing the nuances of his own feelings about them, or inflating their words into grandiloquent monologues, to the point that the emotions—along with the layers of meaning that should be profound—are difficult to convey to the reader.

But criticisms aside, it's undeniable that EG demonstrates Ocean Vuong's ability to capture the shades of despair with nuanced prose and sometimes create a strange humor from human suffering. There's something both funny and touching about the idea behind the scenes between Grazina and Hai—Grazina tormented by post-traumatic stress, and Hai, the skinny Vietnamese-American youth, trying to pull her back to reality by imagining himself as a US Marine rescuing her. After all, humor can be restorative by tapping into a deep sense of human connection—a connection often excluded from everyday life, which lacks imagination and dreams.

But the problem lies not in the idea, but in how Ocean Vuong develops it. When the half-touching, half-bizarre scenes between Hai and Grazina appear too frequently, scattered throughout such a long novel, the reader begins to feel that EG is stuck in its own impasse.

EG should perhaps be seen as part of writers' efforts to explore the dark areas—in the soul and in society—that form in those parts of America where the American dream has not only faded but seems to have never existed. This mood was strikingly depicted in J.D. Vance's non-fiction work "Hillbilly Elegy" (2016) and on the big screen in Chloe Zhao's Oscar-winning film "Nomadland" (2020).

Undeniably, Ocean Vuong has chosen a challenging theme: EG focuses on the solidarity among people at the bottom of American society—their struggles to make a living, the harsh realities of life on the brink.

Some readers may praise Ocean Vuong's humanistic and socially committed spirit in taking on this challenge. But whether his work is a coherent novel is another story.

|

Portrait of Ocean Vuong. Photo: The Guardian |

Portrait of Ocean Vuong. Photo: The Guardian

According to Time magazine, the work is one of the most anticipated books of the year. "The Emperor of Gladness," completed by Ocean Vuong over five years, has received many positive reviews from critics, made it onto Oprah's Book Club selection, chosen by Oprah Winfrey, and is on The New York Times bestseller list. Ocean Vuong, 36, is a poet and novelist. He was born in TP HCM and grew up in Hartford, Connecticut (USA). In 2016, his debut poetry collection "Night Sky With Exit Wounds" won the T.S. Eliot Prize, a prestigious award for the best poetry collection published annually in the UK and Ireland. His debut novel, "On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous," published in 2019, is being adapted into a film by A24.

Cameron Shingleton