Africa has achieved a significant victory against bacterial meningitis, a disease that once plagued 26 countries in its "meningitis belt." Widespread vaccination efforts, particularly with the MenAfriVac vaccine, have led to a more than 99% reduction in disease incidence, preventing nearly one million cases. This success comes after decades of fear and devastating outbreaks that caused high mortality and severe long-term health issues.

For decades, nations stretching from Senegal to Ethiopia endured cyclical meningitis outbreaks every 5 to 12 years. These epidemics had mortality rates reaching 80% if untreated. Even with early detection, about 10% of patients died, and 20% of survivors suffered severe sequelae, including deafness, limb loss, or brain damage. The human cost was exemplified by Jean-Francois, an 18-year-old footballer in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso, who in 2006, after surviving meningitis with intensive treatment, lost his hearing. Months later, he died in an accident after not hearing an approaching truck. His story became a symbol of the suffering meningitis caused in Africa.

The scale of the crisis was starkly evident in 1996-1997, when a meningitis epidemic in West Africa affected over 250,000 people and caused at least 25,000 deaths. Communities were paralyzed: markets closed, people stayed indoors out of fear, and the economy stalled. The polysaccharide vaccines available at the time were only used during outbreaks. They offered short-term effectiveness, did not protect young children, and were expensive.

Given this dire situation, in 1997, African health ministers called on the World Health Organization (WHO) to find a long-term solution. This appeal led to the launch of the Meningitis Vaccine Project in 2001. A collaboration between WHO and PATH, and funded by the Gates Foundation, the project aimed to develop an affordable, effective vaccine offering long-term protection against Neisseria meningitidis serogroup A, the primary cause of epidemics.

A key challenge was finding a pharmaceutical company willing to produce a low-cost vaccine specifically for Africa. The research team ultimately partnered with the Serum Institute of India, which committed to manufacturing the vaccine for under 0,5 USD per dose. After nearly a decade of research and trials conducted in India, Mali, and Gambia, the vaccine, named MenAfriVac, was developed.

Burkina Faso pioneered widespread vaccination on 6/12/2010. In just 10 days, 95% of its population aged 1-29, approximately 10,8 million people, received the vaccine. The results were dramatic: cases of serogroup A meningitis almost vanished. This immediate success prompted other countries in the region to universally request access to MenAfriVac.

|

A child in Africa receives a meningococcal vaccine in 2017. Photo: Gavi |

Within 10 years, over 360 million people across 24 African countries had been vaccinated with MenAfriVac. The disease incidence decreased by over 99%, and since 2017, no reported cases caused by serogroup A have occurred. Experts estimate that the vaccine has prevented nearly one million cases.

|

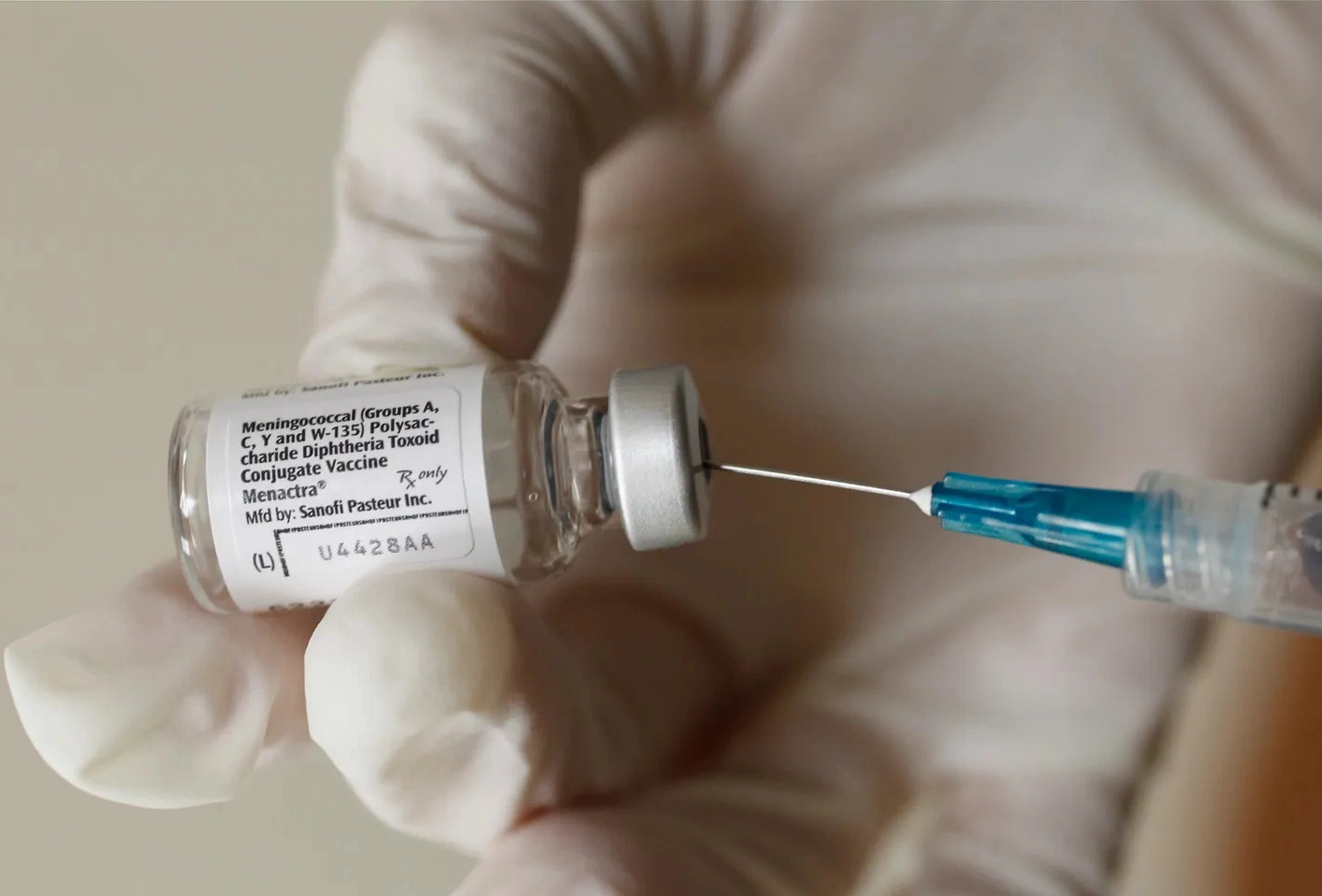

A meningococcal vaccine. Photo: AP |

According to Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, MenAfriVac not only saved millions of lives but also instilled new confidence in communities. This marked the first time a vaccine was developed with active participation from African researchers, from clinical trials to deployment strategies. People felt they were no longer merely consumers of Western products but actively creating solutions for themselves. This success also bolstered confidence in other immunization programs; health managers noted that after witnessing the disappearance of serogroup A meningitis, communities were more willing to participate in other vaccination initiatives.

Looking ahead, in 7/2023, WHO approved a new vaccine, also developed by the Serum Institute of India. This advanced vaccine offers simultaneous protection against five meningococcal serogroups: A, C, W, X, and Y. It is expected to eliminate meningitis epidemics not only in the "meningitis belt" but across all of Africa. WHO recommends that countries integrate this vaccine into routine immunization programs, administering a single dose to children aged 9-18 months. Additionally, supplementary campaigns are advised for the 1-19 age group in high-risk areas. The vaccine is also undergoing further trials in infants in Mali to assess its safety when co-administered with measles, rubella, and yellow fever vaccines.

Van Ha (According to Gavi)